Funerals and cakes. Exploring mortality over tea in Death Cafe Kyiv

Death is not the most pleasant topic for conversation, but sometimes it is worth talking about. At least for those who are overly afraid of it. After all, by verbalizing fears, we dispel them. This is the essence of the Kyiv-based Death Cafe community, whose members meet to talk about the loss of loved ones or exchange ideas about their own funerals in a relaxed atmosphere, with tea and cakes. Daniel Lekhovitser attended one of the meetings – not so much on an editorial assignment, but out of a personal need to share his fear of death with someone.

The rules of the community do not provide for gender restrictions, but there were only women at the table, besides me and the photographer. A lively girl with glasses, apparently responsible for the treats this time, warns me that the cake contains cashews. No one is allergic to nuts, and the five guests continue the conversation enthusiastically.

"There were times when death was not perceived as it is today," says a woman with a fancy hairstyle. "Take the Middle Ages: fairs were organized right in cemeteries.”

Everyone in the room nods. The conversation continues with a discussion of cremation and funerals of the future, when bodies will be catapulted into the stratosphere. A girl with glasses catches my eye and offers me more coffee.

Contrary to expectations, there is almost no afterlife paraphernalia at the meeting of the community called Death Cafe. This is not a Tim Burton fan club. The idea behind the gatherings is to dispel fears about death by talking about it in a casual way, without candles or a black dress code. So there is no organ music playing from the speakers, and coffee is drunk from cups – not skulls. Only a pixelated skull is present on the dial of Vira's electronic watch, and Olena, a novice photographer, has shiny bones playing behind her hair strands.

"Custom-made earrings," she proudly announces, showing off two skeletons.

There is no afterlife paraphernalia in Death Cafe. This is not a Tim Burton fan club

Meanwhile, another participant of the meeting, a fragile woman in a woolen dress, is sitting comfortably with coffee on the couch.

"In a novel I read," she begins, "the hero believed that death should be met like a bride…”

Sound advice, if the "bride" warns you in advance of its visit. Otherwise, there is a risk of meeting it unprepared, in your underwear.

Mauvais ton

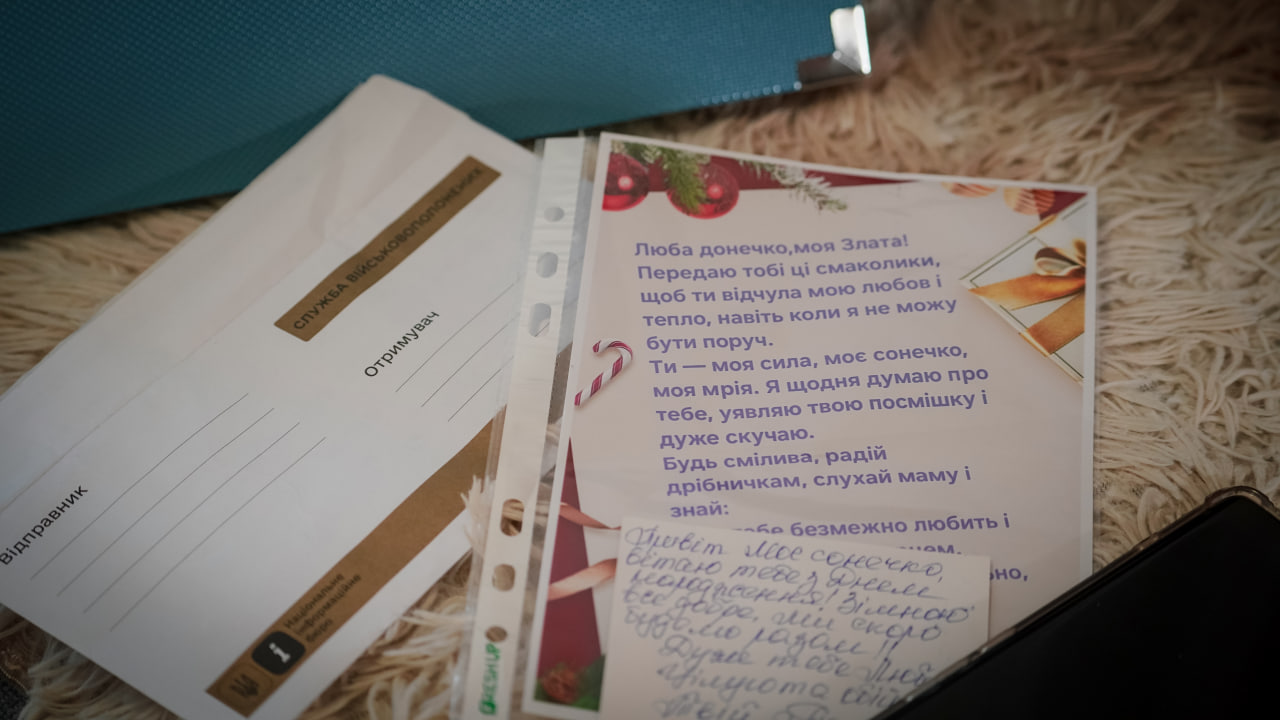

I don't always follow the safety rules during air raid alerts, but that night in Zaporizhzhya, shortly after the siren, I heard explosions coming from very close by, so I moved to the bathroom. At 1:32 a.m. a missile hit my home. The first thing I saw was blackness. The first thing I thought was that this must be how people die, one moment and you just have the light turned off.

I felt myself, as if to make sure I was still alive. I felt warm blood, felt pain. But I did not rush to conclude that I was not dead: I read somewhere that during death, the brain releases so many neurotransmitters that a person dying seems to still feel something.

My head and torso were sandwiched between two concrete slabs, my feet were mired in a thick mess of construction waste. Ice-cold water from a broken pipe was hitting my back. Later it got difficult to breathe as I was running out of air.

It took two hours to dig me out. In the room next to me, a piece of S-300 was found, and near me, the dead bodies of the neighbors from above – thrown into my apartment by the explosion. I survived, but for another three days, I doubted it. Sometimes I looked at my hand and thought it was fake. I asked my company if everything around me was real, if I was really me.

One of my female friends concluded that I had realized my mortality. She said that even for civilians who have heard explosions hundreds of times, war is just sound and vibration. In her opinion, I felt the war by touch.

Now, during air raid alerts, it seems to me that my chances of surviving the war are much lower than those of others. The common reassurance that "it won't happen to me" no longer works.

In the room next to mine, there was a piece of missile, and not far away, the dead bodies of my neighbors – thrown into my apartment by the explosion

Later, I noticed that I needed to talk about death, but I had no one to talk to. My mother believed that such conversations attracted negative events. As an alternative to gloomy conversations, my grandmother would offer me a huge portion of mashed potatoes to keep me quiet and eating instead of talking. My friends also avoided mentioning the inevitable by hastily changing the subject. Either to distract me from my depressing thoughts or to distract themselves.

I had heard about Death Cafe, so I easily found it by googling it. Going to the meeting, I wanted not only to talk but also to understand why, in a country where every adult has probably thought about their own death, it is a mauvais ton to mention it out loud.

Double trouble

Vira Kravchenko, the founder of the Kyiv-based Death Cafe, usually gathers like-minded people at her home. At the appointed time, the photographer and I go up the "Rapunzel’s Tower" – as Vira calls the narrow spiral staircase leading to her apartment in the Vynohradar neighborhood. Vira moved here recently. Previously, her windows faced the memorial cafe, but now they face the Institute of Aging and Gerontology.

In 2010, Vira was, as she says, "caught up with a double trouble." Her father, a diplomat in Syria who had been working abroad for most of his life, finally decided to return to Ukraine and retire. He packed his suitcase, waited for a taxi, and collapsed near the car with a heart attack. Three months later, Vira's mother committed suicide.

At the time, Vira recalls, she knew little about death and mourning and did not understand her father, who had once come from the United States to Ukraine to wash the body of his deceased mother, Vira's grandmother, with his own hands.

"Maybe now I would have washed my parents' bodies myself, held their cold hands instead of handing them over to the funeral service, which buried them in zinc and chipboard coffins," she says.

Vira does not like that funeral homes work like a fast cleaning service, and cites Victorian Britain as an example, where the dead were kept on their deathbed for several days – so that all who wished could say goodbye to them.

Now I would wash my parents' bodies myself instead of giving them to a funeral service

Vira says Death Cafe was not her therapeutic project as she was not looking for answers from visitors to better cope with her parents' death. Rather, she was looking for a community of people who meet from time to time to share their thoughts about death in a friendly atmosphere.

The black magic club

At the meetings, guests always have something to nibble on. This is a conceptually significant condition: we eat, we are alive, we are not dead. Although, despite the name, this is still a discussion club, not a gourmet circle.

The first Death Cafe also known as Café mortel, was founded by sociologist Bernard Crettaz in 2004 in the Swiss town of Neuchâtel. Crettaz was researching funeral rituals in the Alpine regions, and to ease the tension of asking about difficult topics, he offered his interlocutors to have a conversation over a glass of wine and snacks.

The idea was picked up and improved by the Britons: UK Death Cafe organizers book tables in cafeterias with mint-pink interiors, where people chat about tombstone design and technologies for turning their own bodies into compost over cocoa and cookies.

According to Kravchenko, she hasn't been able to implement Death Cafe in Ukraine in the European way as confectionery owners don't want to deal with "black magic". Therefore, meetings have to be organized at home.

"Never mention rope in the house of a man who has been hanged," Vira begins. "In a world where everyone dies, you don't talk about death. But that's what we're here for.”

The organizers book cafeterias with pink interiors, where they discuss turning the body into compost over cocoa

The discussion has begun. Victoria sits to the left of me. She says that death haunts her: several of her friends have committed suicide. She is also interested in reading about the deaths of celebrities, in whom she finds herself reflected (she mentions Heath Ledger and Marilyn Monroe). Olena with the skeleton earrings takes the floor next. She is a student at the Kharkiv Academy of Arts, and in her thesis, she explores the connection between photographs and the dead – any person in the picture is already dead for the next generations of viewers. Oleksandra is a TV presenter, and she talks about death with a smile, as if she were telling a joke. Tanya, a Gestalt therapist, believes that martial artists plan their own death dates and die punctually at the appointed time. Lesya, a psychologist, grew up in a village where death was "organically woven into life": together with other children, she used to search the cemetery for candy left for the dead.

For some time, the discussion swings from topic to topic, with everyone eager to share their own experiences. Oleksandra tells how her grandmother's death certificate was hidden from her. Vira describes what a decent death is in her understanding.

There is no avoiding the esoteric: "After death, you go to the world that you believe in." Vira cuts off such conversations, as there are two things not allowed at Death Cafe: starting talks about the afterlife and trashing each other's religious dogmas.

Eventually, we find a common theme: our own funerals. The audience gets animated. Almost everyone has already thought about how they would like to embark on their last journey. And everyone is annoyed that they cannot discuss this with their loved ones.

"It's infantilism," Tanya, a Gestalt therapist, gets angry. "I'm surprised that in a country where there is a war and people are dying every day, someone is trying to push away thoughts of death.”

According to anthropologist Ernest Becker, this can be explained by cultural patterns. For example, the European canon is characterized by the motifs of immortality or resurrection (anything but dying). In some cultures of Asia and Latin America, however, death is not something to be separated from life at all: in Indonesia, mummified bodies of relatives are kept at home, and in Bolivia, human skulls are used to decorate interiors.

The first to talk about her upcoming funeral is photographer Olena. The most important thing for her is practicality. The burial place should not turn into a burdensome piece of property, like a grandfather's garage on the outskirts of town, she says.

"The thing I hate most is going to the cemetery, cleaning the gate, and the ironwork around the grave. This terrible white spirit, these brushes. I don't want anyone to go through that because of me," Olena grimaces.

"I saw a funeral on Tik-Tok that I quite liked," TV host Oleksandra continues. "The body is placed in an autoclave with liquid nitrogen and then broken down into fine particles. They are put into a capsule with special microflora, planted in the ground, and eventually a tree grows."

Next, we discuss the Capsula Mundi (an egg-shaped urn that decomposes without polluting the soil), the benefits of eco-friendly burial, and the fact that non-traditional funerals are usually expensive and not always legal.

"Burying people is profitable," says Vira, "so the funeral industry belongs to the state. But we need to talk about how to resist this. Everyone is tired of boring rituals. For example, one of the former members of our cafe said he wanted to organize a funeral rave.”

This is where Oleksandra comes into her own. She talks enthusiastically about her friend who had cancer and planned her own funeral in detail.

"She was a cheerful person," Oleksandra recalls. "Cancer, remission, cancer again, chemotherapy, and she washed it all down with her favorite bubbly. I don't know, it’s mysticism: there was so much strength in her that it was transferred to the things around her. Even the roots of the flowers that my friend left for me broke through the pot.”

When her friend passed away, Oleksandra took into account all her dying wishes, except for one: she did not dare to write See you later on the gravestone. But her friend's coffin was lowered into the ground of the Baikove Cemetery to the baritone of Barry White, who sang Never, Never Gonna Give Ya Up from the speakers.

“I have already told my husband how I want to be buried. But what if our apartment is struck and both of us are killed? Then no one will know what I wanted," Lesya says excitedly and begins to announce the list of things she needs as if we are to become organizers.

See you later

Watching how sincerely these strangers exchange feelings and thoughts that they cannot share with their loved ones, I wonder if such meetings have a therapeutic effect. After all, did I feel better in the circle of those who do not run away from talking about death?

The coffin was lowered into the ground to the baritone of Barry White singing Never Gonna Give Ya Up from the speakers

Hardly. Visiting Death Cafe prompted the thought that such meetings are armchair tourism. Knowledge of facts about another country is not equivalent to travel, exchanging opinions is not gaining experience. Perhaps rationalization of death does not help overcome fears. Perhaps conversations about death are not throwing away the shield, but building another protective mechanism. It seems to us that by verbalizing our conclusions, we better understand the unknown.

"Did all this knowledge and meetings help you prepare for death, your own and of your loved ones?" I ask Vira.

"No," she frankly admits.

Vira looks at her watch – three hours have passed, and Death Cafe is closing. I refuse to take some cake home, tell everyone “See you later”, and return to the place where I am guaranteed to get a joke or an extra portion of mashed potatoes instead of talking about death.

Death Cafe did not become a place that gives answers to all questions. I didn't get any reasoned opinions on why Ukrainian society taboos death even in times of war, I didn't find new friends, I didn't feel the therapeutic effect, and I didn't stop being afraid of death.

Instead, I realized here what the hero of one novel had in mind when he advised: if you want to talk about something you can't discuss with loved ones, get on a tram – there you can tell your fellow passenger anything, since you'll never see them again.

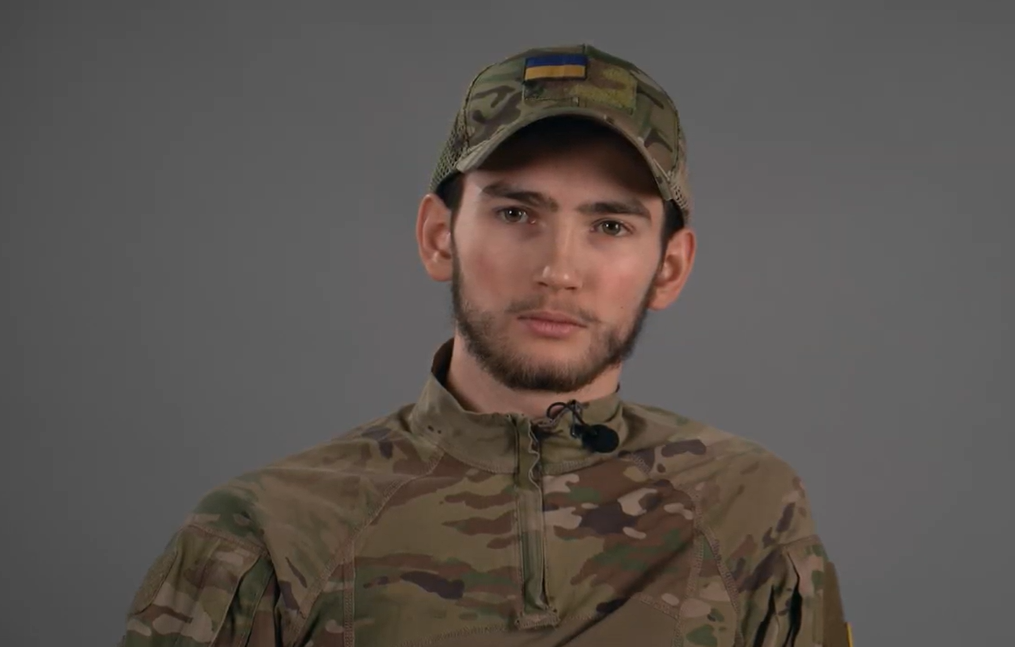

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin, exclusively for Life in War