Paul Smines' burden

Norwegian Paul Smines is a veteran of UN peacekeeping missions in Lebanon and the former Yugoslavia. He was nicknamed "Doc" for his work as a paramedic and ambulance driver. He was a captive of the Serbian army, suffered from PTSD, tried to commit suicide, and worked as a bodyguard for Tina Turner until he began delivering the ashes of Ukrainians who died in Norway to their homeland. To understand why Paul Smines is doing this, a Life in War journalist traveled 1,500 kilometers with him.

To save time, Paul Smines (“Doc” to his friends) always eats while driving. After buying a sandwich at the gas station, he returns to his gray Opel Vivaro, puts the key in the ignition, and taps "Oslo-Bergen-Lviv" into the navigator. Behind Doc, in the luggage compartment, there is a coffin with a body and an urn with ashes.

Ignorance is bliss

It takes three days to get from Norway to Ukraine. During this time, the body will begin to emit an odor. Thanks to the zinc upholstery in the coffin, it is almost unnoticeable. However, an unaccustomed nose still recognizes sweetish notes in the air, as if the van were loaded with rotten apricots.

The secret, according to Doc, is that the smell should not be covered up – you have to get used to it. Amateurs try to mask it by chewing gum or rubbing menthol paste into their nostrils. This is a mistake: your brain will remember the combination of smells — mint and corpse stench — and then you'll feel rot every time you chew an Orbit.

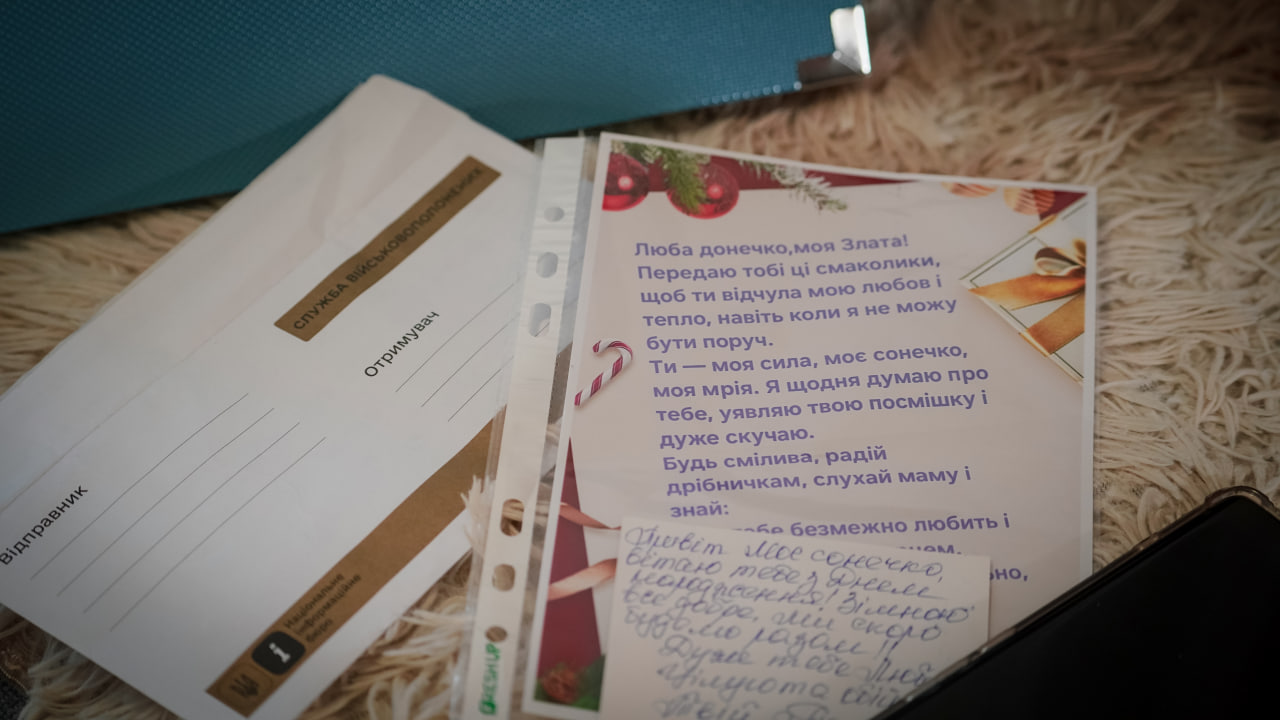

Vira is in the coffin. A little less than five kilograms of ashes remained of Vladyslav, placed in an ivory-colored urn. While loading the remains, Doc does not look through the documents to find photos of these people. Doc doesn't try to find out anything about them at all. He says it's easier that way.

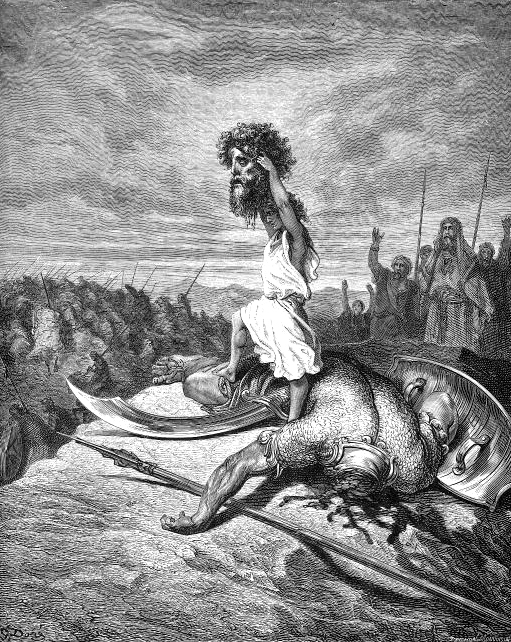

On the way to Poland, the Opel drives onto a ferry in the Swedish port town of Trelleborg. Doc sees the ferry crossing as a dark mythology and jokingly calls himself the Norwegian Charon. This is his ninth "trip across the Styx" — as many times as Doc has delivered Ukrainians who died in Norway to their homeland. In six hours, he will be in Poland, and in twelve more, he will cross the Ukrainian border.

Captivity, Zen, and crisis management

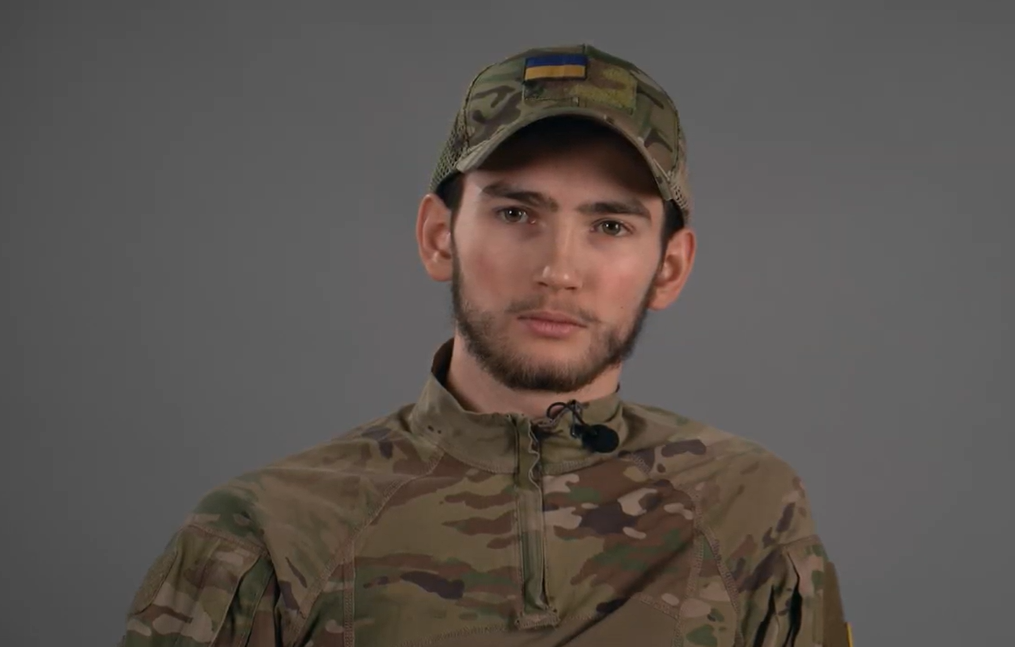

Norwegian Paul Smines is 56 years old. He opts for unobtrusive clothes, has a neat goatee, and always has a furrowed brow along with his smile. This is the look of a man who has spent almost his entire life in adversities: rescuing earthquake victims in Haiti, UN peacekeeping missions in Lebanon and the former Yugoslavia, captivity, depression, drunken fights at biker veterans' meetings in New Orleans.

Doc's father was an alcoholic. The words he used to say to his son most often were dra til helvete — "fuck off". To impress his "old man," Smines signed a contract with the army but failed. The old man was not impressed.

Smines jokingly calls himself the Norwegian Charon

In 1992, Smines exchanged the polar cold for the Balkan heat. He was a driver of UN medical aid in Croatia, was captured by the Serbs along with a Dutch soldier, and had every chance of dying if his fellow soldier had not managed to escape and inform international troops about the place where the prisoners were being held.

However, returning home was not a pleasant experience. In Norway, Paul experienced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. The search for a solution didn't last long: if you can't adapt to the circumstances of civilian life, then go back to where your survival skills would be useful. In 1993, Paul went as a paramedic to North Macedonia on the border with Kosovo, and in 1995, to Bosnia.

War failed to cure his PTSD. In 2000, Doc made an unsuccessful suicide attempt. After his rehabilitation, he became a crisis management coach, worked as a bodyguard (in particular, for Tina Turner during her Scandinavian tour), and began to do what he calls unfunny stand-up called "Men, Zen, and the Art of Talking About Emotions," in which he urged men not to hide negative feelings from others.

Escape from boredom

Doc is not very good at explaining why a citizen of the richest Scandinavian country is not enjoying his retirement surrounded by picturesque fjords. The conversation touches both on the lack of adrenaline and the statistics showing that in the United States, every day, 22 veterans who have lost interest in life after war commit suicide. A shark has to keep moving to avoid drowning, so no retirement among the fjords for him. Smines admits that he came to Ukraine because he was bored in Norway. He's "too old for this shit" to fight the Russians, but he can still be useful in the rear.

Doc decided to deliver the bodies of dead Ukrainians to their homeland when he saw a TV story where a Ukrainian woman named Maryna talked about the murder of her younger sister in a center for displaced persons in Bergen. The murder was committed by her ex-husband. Through journalists, Maryna said that the Norwegian government could not return the woman's cremains, so she needed help. In two months, Doc will spend $3,000 from his own savings on gasoline and ferry tickets and bring the ashes from Bergen to the village of Ustyvytsia, Poltava Oblast. When asked why, Paul responds with a silent grinding of nicotine gum. He does not know why. Or he doesn't want others to know.

About 72,000 Ukrainians emigrated to Norway because of the war. Now, whenever one of them dies in Bergen or its surroundings, they call Doc. This time, he is bringing to Ukraine the ashes of Vladyslav, who committed suicide, and the body of Vira, who passed away from cancer.

The Norwegian authorities allocate 7,000 kroner ($639) to pay for funeral services for Ukrainian refugees, which is only enough for cremation. Relatives pay for the permit to transport the body (9,000 kroner or $821) and the transportation itself (31,000 kroner or $2,827) at their own expense. To help the families of the deceased, Smines cooperates with foundations that cover part of the costs.

Trucker

Is it necessary to know the stories of the dead when you are a mortician, pathologist, or, like Doc, a body delivery man? Hardly. Paul Smines admits that the fate of passengers does not concern him: "There were always either corpses or dying people behind me. I was an ambulance driver in hot spots. You could say I'm a taxi driver for the dead."

In Lviv, in the hotel parking lot, Kris gets into our “taxi”. Thin, almost two meters tall, with semi-gray long hair, he looks like the witcher from the eponymous TV series. Kris, a former Polish model who used to prance the catwalks of Beijing, Paris, and New York, is now making a documentary about the journey of Doc, whom he met at a Ukrainian refugee camp in Poland.

The first port of call is Svitiaz, Volyn Oblast, where Vira's body is to be delivered, then Rivne, where Vladyslav's ashes are awaited. The Red Hot Chili Peppers are playing in the van, and the driver nods along. Doc's high spirits make it seem like he's driving an ice cream truck.

I am a taxi driver for the dead

It is easy to understand the interest of the newly minted documentary filmmaker Kris in the story of Paul Smines. When you hear about the Norwegian Charon, you think that traveling with him is a Jack Kerouac-esque road story, a ready-made plot for an art-house documentary full of philosophical conversations while the scenery outside the window changes.

The reality is different. Outside the window is only an unchanging gray scene, the radio plays repertoire of Ukrainian pop music. Our stomachs are heartburn from hot dogs. Although Doc's work seems bizarre and romantic, it is actually not much different than that of a trucker. Smines has repeatedly said that he lacks adrenaline. However, even this current affair lacks it, as the Norwegian's hearse has never ventured close to active war zones.

Delivery of grief

Near the town of Svitiaz, Doc's van suddenly stops in the middle of a hop field, near a bus stop that stinks of urine.

"I can't come dressed like this," Smines says, taking off his sweatshirt and putting on a white shirt with a black tie.

Meeting families is the difficult part of the job. They are grateful, but not happy to see him. Now too: the group of men waiting for Vira’s coffin is visibly nervous. Noticing Kris's camera, two young men in black indignantly cover the lens with their hands. A commotion breaks out. One of the guys clenches his fists, but when they see Doc with a tie, with official documents, they all calm down.

None of the people present knows how to bring the coffin with the deceased into the house: head or feet first. Doc is unable to help as he has only ever dealt with cremation urns. In an effort to resolve the uncertainty, one of the relatives googles the tradition on his phone. Meanwhile, Paul sees the woman whose body he brought for the first time: next to the bread and candle on the table is a photo of Vira.

Paul quietly says goodbye and goes outside. For the relatives of the deceased, he is, as he says, just a service worker. He says he is not invited to the ceremony, just as a postman is not invited to read the letter.

Doc is not offended. Indifferent to the dead, he suddenly shows genuine care for their loved ones. "Relatives are the most suffering side," he says. "You need to empathize with them, not the dead." It seems for the first time during this period, the author of the unfunny stand-up "...the Art of Talking About Emotions" brings up a conversation about his own feelings.

Paul Smines’s duty

The second stop is in Rivne Oblast. Through the Nove cemetery, a funeral procession of seven cars follows a white electric bus. Inside it are the parents of the deceased, who are gently hugging a cardboard box with an urn in four hands. The 27-year-old Vladyslav was searched for by 130 rescuers, helicopters, drones, and dogs. The body of the hanged man was found in a forest in Bjørnafjorden.

Smines cannot hide his affliction. His eldest son was a little younger than Vladyslav when he died of an overdose 11 years ago. Doc reiterates that death is just a biological state, and the ashes of the deceased are just ashes. But he doesn't seem to believe it himself. Paul Smines finds it increasingly difficult to pretend to be an insensitive taxi driver who is willing to carry any kind of cargo to avoid being bored at home. Doc admits that he despairs of a columbarium or, worse, a random closet in a foreign morgue where the cremains of a man who will never return home will be kept.

Vladyslav's ashes have returned home, but what happens to them afterward does not satisfy the Norwegian. There is no columbarium at the cemetery, and the cremation urn in the grave dug for a coffin looks guiltily small. An excavator smells of engine oil nearby. As soon as someone starts to speak, a car driver starts a loud engine, and the words are drowned out. The man trying to lay the wreath gets stuck in the mud, loses his shoe in it, and carries on without it.

It is difficult to avoid the obvious comparison between Smines and Charon, although their approaches to work are completely different. The ancient Greek ferryman transports the souls of only those dead whose bones are buried in graves. Smines transports those who need these graves. However, they do have something in common: they both work because of a call of duty. Charon owes it to the god of the dead, and Smines owes it to the dead themselves, whose needs cannot be met by anyone but loved ones or those who sympathize with them because they have experienced loss themselves.

The gravediggers are still filling the pit with earth when the procession begins to disperse. Doc and Kris stay by the grave. The Norwegian looks too depressed even for something as grim as a burial. The ceremony, for which thousands of kilometers were traveled, was supposed to be different in his mind. "That’s all?" he mutters. Kris doesn't hear him, as he shoots a panoramic view from a distance: the Norwegian Charon, alone, next to a cross.