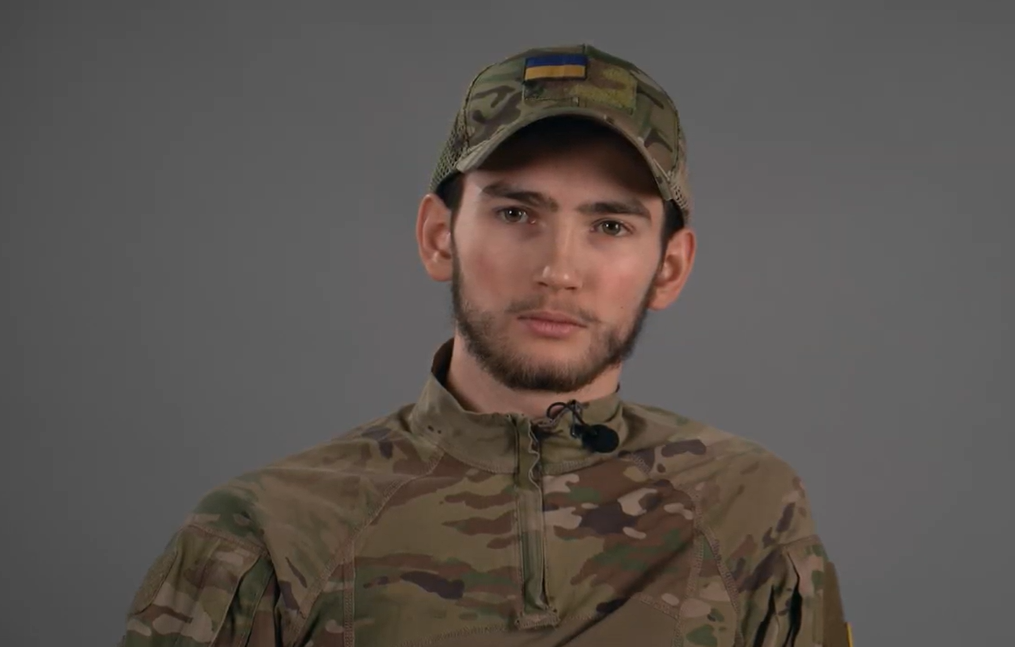

Deaf Ukrainians still use Soviet sign language. To transition to Ukrainian, it needs to be created

A universally understandable sign language for all deaf individuals does not exist. People with hearing impairments in different countries communicate using their own sign languages — there are about 300 worldwide. The Ukrainian sign language began to form but was replaced in the 20th century by a language standardized for all republics of the former Soviet Union. Now, deaf Ukrainians are creating their own language. To make new signs intuitive and widely accepted, their creators are involving thousands of other Ukrainians with hearing impairments in the language-building process.

Larysa Kuzmenko, a 31-year-old confectioner from Odesa, also teaches culinary courses. She sends her students video recordings of recipes and text messages. To place an order in a cafe or request a consultation at a bank, Larysa shows the text typed on her phone to the person she's speaking with. Her written Ukrainian isn't perfect—having had a hearing impairment since birth, Larysa structures sentences in an unusual way. However, she mostly manages to convey her meaning.

Kuzmenko was born into a family of deaf people. Most of Larysa's close relatives also have hearing impairments. In face-to-face interactions, she uses sign language. Online, she communicates similarly by sending video messages via Telegram. People without hearing impairments rarely communicate with the deaf, so they mostly remain in a closed social bubble: they receive information from each other and from deaf bloggers. They hardly watch TV because even state channels seldom provide interpreters. Subtitles partially address the issue, but unlike sign language interpreters, text cannot convey intonation and emotional nuances.

Recently, Larysa added the USL UTOG (Ukrainian Sign Language of the Ukrainian Society of the Deaf) account to her most visited ones. In this account, she and other deaf people decide what their new sign language should look like: They watch videos with sign options and vote for the best ones. The latest sign Larysa commented on was a hand motion that looks like grinding something into powder, which means "color."

How sign language is used

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 2018, 400,000 Ukrainians use sign language (hearing impairment does not always mean complete hearing loss, so not everyone needs sign language).

{{quote-7="/quote-block-list"}}

Sign language is structured differently from spoken language. Sentences always start with the subject. The phrase "On the table, there is a cherry pie" in sign language would be structured differently: "Pie cherry is on the table." Deaf people usually follow this rule in written language as well.

Deaf individuals use signs to convey words or phrases. If there is no specific sign for a word, it is spelled out letter by letter using the sign alphabet, known as fingerspelling. Fingerspelling can be quite cumbersome — for example, deaf scholars from different countries are now trying to standardize signs that convey scientific terms to avoid constant fingerspelling.

Gesturing relies on hand positions, sharpness of movements, and facial expressions, which not only add emotional color but also affect the meaning. Linguist Natalia Adamiuk provides a telling example: a crossed right hand over the left with a neutral facial expression means "cross," with a slightly open mouth and a slightly protruding tongue — it means "unfinished work," and with furrowed brows and lips pursed—it signifies "impossibility of something."

The Soviet influence

Many countries have their own national sign language, although there are exceptions: for example, in Monaco, the deaf communicate in French. There are about 300 sign languages globally, divided into nine language families. The most widespread is Old French, which includes 26 languages.

In Ukraine, the deaf use both Ukrainian and Soviet sign languages.

The Soviet sign language (used, for example, by Larysa Kuzmenko from Odesa) is identified globally as Russian. However, Ukrainian linguists Natalia Adamiuk and Arkadiy Bilozovskyi believe it is more accurate to call it Soviet. They point out significant differences between the language still used by Russians today and the one that was once standardized for all republics of the former USSR, replacing their authentic languages.

The authentic Ukrainian Sign Language (USL), like Russian, belongs to the Old French language group. The emergence of USL dates back to the first half of the 19th century when schools for the deaf began to appear in Ukraine. The first such school opened in 1805 in the town of Romaniv, Zhytomyr Oblast. Later, Austro-Hungarian schools appeared — in Lviv in 1830 and Odesa in 1843.

In the 1930s, Russians began to implement a unified sign language — the Soviet sign language — in the USSR, which was created based on Russian with the addition of signs from the national languages of other republics. Soviet sign language was introduced in workplaces where the deaf worked. It was also used in schools for children with hearing impairments. For some time, certain educational institutions in Ukraine continued to use USL, but it was banned in 1950.

Under these circumstances, the Russification (or rather, Sovietization) and subsequent degradation of USL began. Young people, who were supposed to inherit the signs of USL, moved to central regions of the country and learned Soviet sign language. With the death of USL speakers, authentic signs also disappeared.

_11zon.jpeg)

USL has partially survived and is still in use. But today, it's hard to assess its conformity to the pre-Soviet original. Hypothetically, if in USL the word "very" is depicted almost the same as in Soviet — by a movement as if spreading something on bread — can this sign be considered borrowed? What if it existed in the authentic language?

According to Ihor Shavro, a sign language interpreter for Pryamyi TV channel and Suspilne, there was a noticeable difference between USL and Soviet language: USL, judging by its authentic signs, is more plastic — characterized by softer and more fluid movements.

However, a detailed understanding of how the authentic USL differed from the Soviet sign language is impossible due to the lack of historical materials. The very nature of sign language makes documenting its development challenging: unlike spoken language, previous samples of which are preserved in written materials, signs had to be depicted in drawings. But this is labor-intensive work that is often ignored in a non-inclusive society. There were no visual dictionaries of pre-Soviet USL. Moreover, there is still a shortage of sign language primers in Ukraine, so a person who loses hearing will have to learn signs through YouTube or in classes with specialized instructors.

Research would help understand how Russified the modern USL is, says Adamiuk, but due to a lack of funding, it is not conducted. She suggests that the adoption of the sign language bill by the Ukrainian parliament could provide a push, one of the articles of which provides for scientific research and analysis of USL nuances.

Language reconstruction

After the Russian invasion, Larysa Kuzmenko began learning USL. She admits the transition is challenging: unlike spoken Ukrainian, which Russian-speaking Ukrainians can understand well, USL is not understood by Soviet language speakers. So a person learning USL must encourage their social circle to follow suit.

Kuzmenko has already switched to Ukrainian in communication with her mother and friends, but sometimes they have to switch back to Soviet as USL simply lacks its own signs.

During the full-scale invasion, the theater's actors performed in Poland and Croatia.

In the summer of 2023, members of the Ukrainian Society of the Deaf (UTOG) created an expert group on de-Sovietization. The experts' task is to develop new signs for USL to replace Soviet ones.

The group consists exclusively of the deaf, working in four departments: seekers, linguists, media workers, and a creative section. Seekers identify Soviet signs in USL. Then, linguists and creative group members become acquainted with these signs and develop two to three replacement options. Videos with new signs are posted on the UTOG website (as well as on Instagram, Facebook, and Telegram). Registered deaf members of UTOG decide which sign will be approved and whether it needs improvement through online voting. Sometimes users do not accept any of the options. Then, the expert group must develop new signs.

For example, until recently, deaf Ukrainians used the Soviet sign for "interesting" ("interesno"). In 2023, the commission proposed a new sign — "tsikavo" (interesting): a double tap on the eye with the index and middle fingers. This gesture comes from the sign for "see" (index and middle fingers touching both eyes). Thus, "tsikavo" (interesting) means something that catches the eye. The website users approved the new gesture, and it is now officially part of Ukrainian Sign Language.

{{2-ci-g1="/en/custom-blocks-list"}}

A member of the creative group, Oleksiy Nashyvochnykov, says his department's task is to bring the new sign language closer to the Ukrainian spoken language, which he believes is about 40% different from the Russian spoken language. Ukrainian and Soviet sign languages, in Nashyvochnykov's view, are about 60% similar.

The most challenging part of the work, says Nashyvochnykov, is coming up with a new sign. It has to clearly convey an image or concept and at the same time be connected to the Ukrainian word. For example, the names of the months in the Ukrainian language, unlike in many others, are not etymologically related to the names of ancient Roman gods. Therefore, the signs must incorporate the associations already embedded in the names: January (“sichen”) — touching the cheeks with fingers as if they are being cut by a cold wind; July (“lypen”) — depicting the flight of buds with fingers; May (“traven”) — depicting grass sprouting; August — a sickle cutting wheat.

Sometimes signs come from less obvious associations. For example, the place name "Mariupol": fingers depict the movement of fish fins because the city is known, among other things, for its fishing industry. Some signs are related to historical context. The sign for "Russia" is touching above the upper lip with the index finger (an association with Peter the Great's mustache, which symbolizes Russia in sign language). Therefore, the sign for "de-Russification" in USL is a sharp movement of the index finger as if removing the mustache.

{{2-ci-g2="/en/custom-blocks-list"}}

Reaction of the deaf community

In less than a year, the expert group managed to approve just over 50 signs, although about 2,000 drafts were developed. Oleksiy Nashyvochnykov says the process is slow because it involves voting. The Ukrainian Society of the Deaf (UTOG) could have followed the path of France and Canada, where the approved signs by the relevant state bodies are not subject to public discussion, but the Ukrainian society prefers to consider the interests of the community.

Linguist Nataliia Adamiuk, who also works in the expert group, adds that for UTOG, the quality of the signs is more important than the speed of their approval. In her opinion, the numerous comments and suggestions indicate that the deaf community is taking the rebuilding of USL seriously. The traffic on UTOG's website and social media confirms Adamiuk's words: every month, 50,000 users leave between three and five thousand comments.

Just over 50 signs have been approved, although about 2,000 drafts were developed

To find out how deaf Ukrainians perceive the new signs and generally feel about the idea of de-Sovietizing USL, the editorial team interviewed active commentators on UTOG’s website. According to Anastasiya Chala from Mariupol, not all proposed signs accurately convey the idea behind the word. But there are successful decisions, such as the new sign for "dad": a hand edge movement from the forehead to the chin. "Dad is the head of the family, responsible for the women in the family," says Anastasiya. "Hence the movement from top to bottom, as the feminine gender in sign language is shown in the lower part of the face."

{{2-ci-g3="/en/custom-blocks-list"}}

Twenty-three-year-old Serhiy Soroka from Lutsk, who has lived in London for three years and works as a cashier in a supermarket, is dissatisfied with the society's activities. Serhiy sees no point in abandoning the Soviet sign language to which he is accustomed.

According to the social media editor and UTOG website statistics, exactly half of the 44,000 registered deaf members of the society switch to USL, while the other half prefer the Soviet one. Not all interpreters support de-Russification either. In the opinion of Ihor Shavro, there is a noticeable influence of the Soviet school of translation in Ukraine, whose graduates are conservative and do not even plan to familiarize themselves with the new signs.

Rejection of USL

Larysa Kuzmenko says that switching to a new language is primarily difficult physically because muscle memory interferes: the mind forms a Ukrainian sign, but the hands automatically demonstrate the Soviet one.

The reluctance to learn something new is one reason why the de-Sovietization of USL is progressing so slowly, says Oleksiy Nashyvochnykov. In his opinion, some deaf people reject the proposed signs because they support preserving the Soviet language.

There are those who do not plan to switch to USL because they do not see their future in Ukraine. As of September 2022, 6,199 UTOG members and 32 interpreters (there are 231 interpreters in Ukraine) left the country. However, the numbers have apparently increased over the past year and a half.

There is little hope that a significant portion of deaf migrants will return after the war. Abroad, there are higher benefits, better social conditions, and a better job market. In Ukraine, the deaf usually work in industrial enterprises in positions that require minimal communication and do not provide career growth opportunities. In Europe, they can become middle managers — corporate culture there is more inclusive, and companies encourage employees without hearing impairments to learn the basics of sign language.

{{quote-6="/quote-block-list"}}

Larysa Kuzmenko's brother and many of her friends with hearing impairments have already gone abroad — not only because of the war but also because Ukraine lacks an inclusive policy. She, however, is determined to stay in Odesa and contribute to the development of the new USL.

Oleksiy Nashyvochnykov and other experts note that deaf Ukrainians with such patriotic sentiments are a minority. Ukrainian society does not take care of the needs of people with hearing impairments, and they, in turn, are not interested in social trends such as Ukrainization.

In a conversation with the editorial staff, Oleksiy Nashyvochnykov and Ihor Shavro regret the missed opportunities: after Ukraine gained independence, the deaf community did not undertake de-Russification, as happened in the 1990s in the Baltic states and Georgia after the 2008 war. There, the modern youth almost do not understand Soviet sign language. Now, USL supporters face a double task: not only to create the language anew but also to prevent it from dying in its infancy.