The brink of extinction. Report from Donbas

Russians are approaching Pokrovsk, fighting continues in Chasiv Yar. Vitaliy Poberezhnyi and Serhiy Korovainyi visited these cities to see what life looks like for the military before the front line is likely to be shifted. To do this, they visited one of the last independent volunteer units and a strike group defending the approach to Chasiv Yar.

"Now we're heading straight into the belly of the beast!" shouts "Sanych."

We are inside a Kozak-2M armored vehicle. The driver, code-named "Roshen," is taking us to positions near the water supply station close to Chasiv Yar, a sector Russian infantry have been assaulting almost daily for the past three months.

As we drive, there is no sound of explosions. But silence doesn’t mean there is no danger, and our guides activate electronic warfare equipment to jam frequencies used by FPV drones and Mavic UAVs.

"Otherwise, we wouldn't even make it here," "Sanych" shouts again.

The driver mutters something. Sanych asks him to speak louder. After a blast from a TOS-1A Solntsepyok, "Sanych" has ruptured eardrums and shrapnel in his thigh. He refuses surgery so he can stay on duty.

The Kozak stops. "Sanych" jumps out and immediately falls flat on his face. Because of his barotrauma, he can't hear high-pitched sounds like a mosquito's whine but can detect the whistle of a mortar shell. It detonates somewhere nearby. "Sanych" runs into the bunker.

For ten minutes, "Sanych" and the soldiers sheltering here remain silent as explosions shake the air. The bunker is surprisingly cozy: a carpet hangs from a bunk bed, and a table is covered with a tablecloth. For a moment, a spot of light flashes in the room. The noise from the blast wave echoes in the ears, similar to the sound heard when a seashell is placed against them. A shell fell nearby, and only because of the depth of the bunker was no one injured.

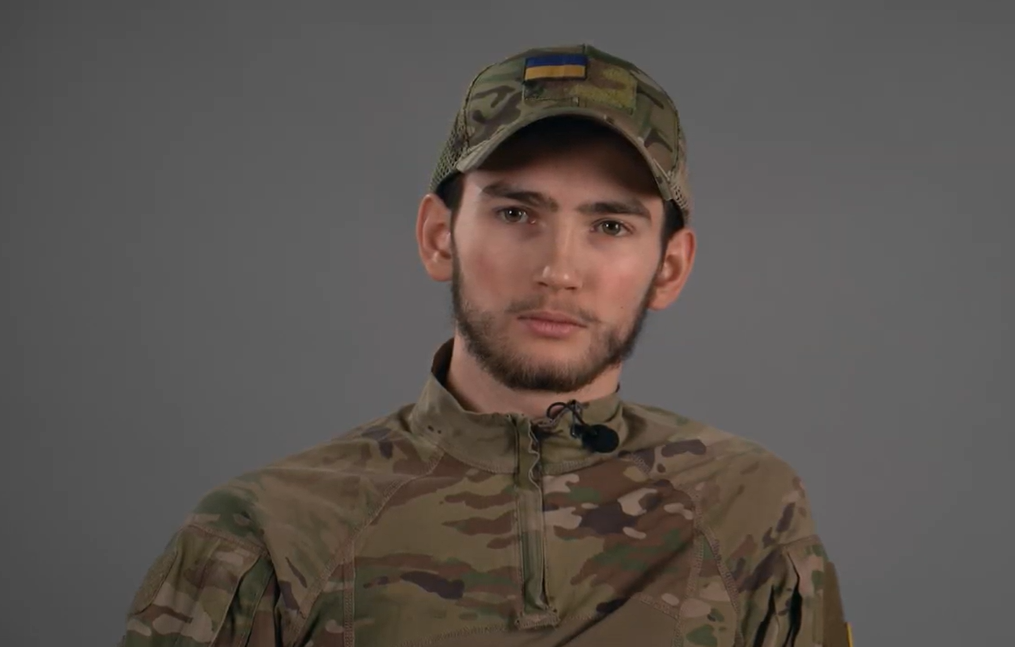

When the shelling stops, we can properly see "Marik" and "Borik," operators and navigators of FPV drones. "Marik" is 35 years old. Before the Russian invasion, he worked as a lathe operator and electrician. He was drafted into the army. "Borik" is 28 but doesn’t share much about himself. Instead, "Sanych" speaks for him: "Borik" has three children. He could have avoided the fight but chose to join the army.

"Marik", "Borik", and "Sanych" are part of the "Black Swan" assault unit of the 225th Separate Assault Battalion stationed near Chasiv Yar. The battalion has seen combat in Bakhmut, Makiyivka, Horlivka, Avdiyivka, and Chasiv Yar.

"Houston, give me the panorama," shouts "Sanych", sitting down on a bench. Opposite him, a screen shows a feed from a reconnaissance drone controlled by an operator in another bunker.

The monitor displays the landscape around the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas canal. The screen is mostly filled with the green forest where Russian forces are positioned. The mission is to prevent the enemy from securing the western side of the canal. Recently, Russian units took over the "Novyi" neighborhood east of the water supply station and are now trying to cross the water barrier.

To ensure a drone's battery lasts for its return, operators position themselves close to the front line. Only 1.5 kilometers separate the "Black Swan" positions and the Russians.

"We've been holding this position for three months," "Marik" says.

"108 days," "Sanych" clarifies.

According to "Marik" and "Borik", they and their brothers-in-arms have eliminated around 400 Russians this summer. The count could rise as the drone operator in the neighboring bunker spots enemy infantry. The screen panorama shifts, showing three Russians digging a trench between tree trunks.

"Borik" runs for a package, returns, and attaches it to a drop drone.

"300 grams of plastic explosive," says Marik, taking the controller. They usually hunt Russians four to five days a week, 12–15 hours a day.

Borik looks at the reconnaissance data and suggests a path. He focuses intently on his work. "Marik" eagerly explains how to control the drone, how long it takes to reach enemy positions, and recalls a successful drop on a Russian bunker, where the lone survivor hid for several days.

The drone is in place.

"It doesn't have to hit directly; just landing nearby is enough," "Marik" says. "The shrapnel radius of the makeshift explosive is 20 meters."

He presses a button, and three shells drop near the Russians. The drop is unsuccessful: only one infantryman is injured. The Russians retreat further into the forest.

"They'll come back again. They're less afraid of us than their own commanders," says "Sanych", hinting that their commanders force them to assault the water supply station despite the losses.

While the Russians regroup, there is time to rest. There are no explosions to be heard. The silence provides a deceptive sense of security. However, when it’s quiet, it’s likely that you’re being watched. Previously, artillery was the primary means of attack. Today, drones often perform artillery tasks. The war is becoming quieter but deadlier.

Drones observe the battlefield, a problem for both sides. Sanych draws our attention to the ground outside the bunker — no cigarette packs, bottle caps, or ration wrappers. If the Russian reconnaissance drone operator spots trash, they will adjust fire to that location.

Because the battlefield is visible, vehicles no longer deliver medicine or supplies to the infantry — drones handle this as well. For the same reason, "Black Swan" avoids rotating soldiers at the positions. Most losses occur when soldiers enter or exit positions.

We killed 400 Russians, but they keep pressing forward because they fear their commanders more than us

Ahead is a short but dangerous sprint — 600 meters along broken asphalt to a neighboring bunker. It's about half a kilometer from the drone operators' position, but it feels like a completely different war here. The bunker resembles a World War I dugout. It is not as deep as Marik and Borik's, and it seems unlikely that you'd get away with just a ringing in your ears if a shell lands outside.

A lamp with an unpleasant pale blue light illuminates two soldiers. They are "Docent" and "Kazhan." The former is from Berdychiv, the latter from Starokostiantyniv. Both joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the spring of 2022. Their working conditions are worse than those of the drone operators: a cramped space with stale air and semi-darkness. Maybe "Kazhan" (“Bat”) got his callsign because he lives like he's in a cave. There’s no time to ask — orders to fire come over the radio.

"Docent" and "Kazhan" exit the bunker to a weapon concealed in thick bushes. The SPG-9 has a range of up to four kilometers. "Kazhan" and "Docent's" shifts last 8–10 days. As they retrieve the mortar, soldiers who seemed exhausted just moments ago spring to life. With economical, precise movements, "Docent" loads a shell while "Kazhan" aligns the weapon with the target. They take about five minutes to set everything up.

The mortar operators put on ear protection. There's no spare for journalists — we are advised to cover our ears with our hands or, better yet, use AirPods. It doesn’t help much: it feels like a tank just fired nearby. The mortar men rip up grass and greenery, covering the scorched earth around them. Whether they hit the target will be communicated later over the radio.

"Sanych" is satisfied — the soldiers work quickly and cohesively. He is optimistic, and his optimism is infectious. After spending a day with him, you become confident that Ukraine can still surprise the Russians and end the war on favorable terms. He believes Russia is in for some unpleasant surprises, which is why he named the assault unit "Black Swan."

The unit's name is inspired by the "Black Swan" effect, where unpredictable factors fundamentally change the course of events. "Sanych" believes his assault unit could be the harbinger of a black swan event. Perhaps he's right: Russia faced a black swan, but not near Chasiv Yar — in Kursk Oblast. Three weeks after our meeting, "Sanych's" assault unit was pulled from the eastern front and deployed to the offensive in Kursk Oblast.

Almost on cue, after the grenade launcher fires, the same Kozak armored vehicle appears. Ahead is the road from Chasiv Yar to Kostiantynivka, and from there, a car ride to Pokrovsk.

The last volunteer battalion

Volodymyr Rehesha, also known as "Santa," is easily recognizable by his white beard and red hat. The earring in his ear, however, makes him look more like a pirate — a comparison Rehesha himself enjoys. He views his battalion as a pirate ship, taking in adventurers who don't want to or can't serve in the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

"Chervonets," a Russian from Tver Oblast, would likely not have been accepted anywhere but the Russian Volunteer Corps or the Siberian Battalion, where other Russians serve. However, "Santa" took him in. For the 62-year-old "Poltava" and the 72-year-old "Didus" (‘Grandpa’), this unit is nearly the only way to fight, as the regular army does not accept those over 60 years old.

Other fighters under "Santa" joined him because they don't trust the commanders in the regular army, who they feel often do not value lives or refuse to fight alongside their subordinates. "Our motivation is simple — our commander is with us, that's all," says Chervonets. Throughout its existence, the unit has lost only three fighters: "Chechen," "Grek," and "Ed," who died after February 24.

"Santa" has been leading the independent volunteer unit for eight years, while nearly all other similar formations have been integrated into regular military structures. Rehesha, a former member of the "Right Sector," created the volunteer battalion in 2016, when most of his brothers-in-arms joined the 67th Brigade. He joined the "Right Sector" in 2014, working with artillery. "Santa" first took command in 2016 during a spring counter-offensive operation in Avdiyivka, where the "Right Sector," the 16th Battalion of the 58th Brigade, and the 74th Reconnaissance Battalion recaptured the industrial area from the Russians. "We had seven automatic grenade launchers, and we shredded the Russians to pieces," "Santa" said in an interview once.

The independence of Santa's unit irritates some commanders. He was asked to leave Avdiyivka and later offered to join the Ukrainian Armed Forces, but he refused. Downsides: the fighters have no salaries, vacations, social guarantees, or awards (volunteers bring homemade medals to cheer them up, and donations cover the unit's needs). Funding and organizing funerals are also problems for the unit. Upsides: they answer to no one and are not burdened by bureaucracy.

The legal status of the volunteer battalion is unregistered. In essence, Santa's men are an organized group illegally possessing weapons. As a result, the unit does not have the right to receive intelligence data or ammunition. In practice, however, they get what they need: over the years, Santa's group has earned a certain level of trust. Ukrainian army units connect them to drone reconnaissance streams, and Santa's people have sufficient experience in firing for commanders to send inexperienced fighters to them for practice, compensating with ammunition.

Santa's people are an organized group that illegally possesses weapons

The unit specializes in 82-mm and 120-mm mortars. Rehesha learned how to use the weapons through YouTube and Google. As he says, "Globally, mortars change nothing," but if you ask Ukrainian Armed Forces infantrymen if they would want an 82-mm mortar covering them, most would probably say "yes."

"We haven't fired a single shot ourselves," says Rehesha. "We conduct operations with the Ukrainian Armed Forces. I remember many battalion commanders, brigade commanders, and staff officers back when they were platoon commanders — everything relies on personal connections. There are proud commanders, but refusing the help of people who've been here for 9–10 years and know every bush is just foolish."

"Santa" and his fighters moved to Pokrovsk just a few weeks ago. Their previous base was near Selydove, which is now on the front line. Before this, Santa's group fought in Avdiyivka, Netaylove, Pervomayske, and Pisky.

The Russians, who are advancing about five kilometers per month in the Pokrovsk sector, could reach the city by early fall. On August 19, the city authorities recommended that residents evacuate. Just three weeks ago, it seemed Pokrovsk's residents were unaware that they would soon have to say goodbye to their city. Sports grounds in Yuvileynyi Park were filled with soccer and basketball players, and there were lines at the exercise equipment. Parents strolled with their children by the lake.

Now, Pokrovsk may turn into a desert. In recent weeks, the Russians have been trying to speed up their advance in this sector, which is why "Santa's" unit is here. Rehesha and his fighters have no obligations: they can move to safer directions or even leave service at any time. However, "Santa" and his men don't consider the years spent in Donetsk Oblast to be "service." "We didn't join the army," says the Russian "Chervonets". They are simply fighting — and choosing to do so in Donbas.

Night hunt

"I'm f**cking sick of it all. I can't take it anymore," was the second phrase we heard from "Romeo".

With his thick eyebrows, sad eyes, and a cigarette between his teeth, "Romeo" signed a contract in 2020 for three years, but now martial law requires him to serve beyond his term.

We are on the road near Chasiv Yar. Before heading to the position of the night drone bomber operators, the driver, "Romeo", in a white pickup, lists potential risks: if an enemy kamikaze drone hits the trunk where the ammunition is stored, we'll all die; if it hits the hood, the driver won't have a chance, but the passengers might survive with injuries; if it hits the wheels, we might all survive.

"Romeo" starts the vehicle and drives into the dusk.

The driver brakes near a forest belt, where the positions of the night bomber crew are located near Chasiv Yar. Two silhouettes emerge from the darkness — "Batman" and "Leo" — who open the trunk and unload crates of shells.

Nearby sits "Pinocchio," the commander of the crew in the 93rd Separate Mechanized Brigade. He got his nickname because of his long nose. He volunteered at the military recruitment office in his native village of Solotvyno in Zakarpattya Oblast. Often, commanders handle conversations with journalists, but "Pinocchio" has no desire to talk. He is too tired.

"Pinocchio" waits until it is completely dark. Navigators "Batman" and "Leo" guide the route, and Pinocchio, using a remote control, lifts the drone into the sky. The UAV flies northeast towards Bakhmut. In 15 minutes, the bomber reaches an enemy dugout and releases three explosive shells, destroying it. The UAV returns with two propeller blades damaged by gunfire.

The drone strike team's commander "Pinocchio" pilots a drone loaded with explosives

"Pinocchio's" team has two models of bomber drones: Kazhan and Vampir, but the Russians call them Baba Yaga. These UAVs are large and slow, so they only fly at night. They carry loads weighing 12 to 20 kilograms, drop them on positions, mine areas, and deliver supplies to the front lines.

Soldiers often name their rifles, grenade launchers, or tanks. There's no point in naming a night bomber as it's a disposable asset. Bomber drones heat up, the Russians spot them with thermal imagers, and they are often shot down with machine guns or rifles. During the second sortie of the night, Pinocchio hit another dugout but then lost connection with the UAV as the Russians jammed the signal. "Romeo" starts up another drone.

"Pinocchio's" crew works at night, about 4–6 hours a day in summer. During the day, the Kholodnyi Yar fighters are bored in a cramped dugout and try to sleep as much as possible to cope with the heat, even when they no longer want to sleep.

At night, soldiers use red flashlights. Red light is not visible from a distance

The atmosphere in the dugout is depressing; the fighters are tired of each other. "Pinocchio" plays the online game PUBG via Starlink. Tens of thousands of players play this shooter every day. It's possible that "Pinocchio" is on the same team with a player from Russia or is hunting them down with a machine gun. He just piloted a night UAV and a few minutes later parachutes from a plane, races on a motorcycle, and shoots with a rifle. In real life, a dozen rocket shells just landed nearby, followed by an aerial bomb explosion. "Pinocchio" keeps playing. He doesn't want to look away from the screen and see his dirty, sweat-covered fellow soldiers.

Usually, an effective way to get soldiers talking is to ask about their home and family. But it doesn't work here. It feels like the night crew is stuck in a state where they don't want to remember the past or think about the future. The conversation doesn't flow, and when "Romeo" shows up, we leave with him.

"What did you do before you were mobilized?" I ask the driver.

"I don't remember. Does it even matter?"