After cyborgs

Reports and pictures from the Donetsk airport made Sergei Loiko one of the most prominent authors covering the Russo-Ukrainian war. The year 2022 could have been the peak of his journalistic career, but Loiko stopped reporting. Daniel Lekhovitser met with him to find out why.

Ten years ago, Sergei Loiko was a prominent chronicler of the Russo-Ukrainian war. He was the only foreign correspondent who managed to get into the besieged Donetsk airport, holding a Russian passport and an American press card. His photographs of the "cyborgs" spread around the world and gained cult status. The documentary novel he wrote about his experiences was nominated for the main Ukrainian literary award, the Taras Shevchenko Prize. Loiko was watched, read, and listened to. Both in Ukraine and abroad. In 2015, in an interview, he compared the Russian army to orcs, and the comparison stuck.

Loiko’s keen eye, writing skills, and recognizability are so needed now when attention to development in Ukraine is fading. Where did he disappear?

A sense of place

Sergei Loiko is not satisfied with the table offered by the waiter. The reporter sits down away from the windows, closer to the corner. Loiko is 71 years old. Broad shoulders, graying beard, pixelated jacket. When he appears, the company at the next table starts talking quieter. For half an hour, the waiter doesn't approach Loiko – apparently, he just doesn't dare to interrupt his story.

Loiko talks about what he knows best – reporting. He has always been on the scene in advance. He arrived in Iraq three months before American fighter jets began bombing Baghdad. In 2013, when the Maidan was still being formed, Loiko was already living in the Dnipro Hotel on European Square.

It's not the journalist’s luck, it's an approach. The essence of this approach, Loiko explains, is to "spot a spark in the hay" in time, run quickly to the seat of the fire, and then wait patiently for it to break out. He compares himself to the Slovenian basketball player Luka Dončić, a slow player who has a developed sense of place: where to pick up the ball in time, where to block the opponent, and where to make a shot.

Loiko correctly calculated the trajectory of the ball. He arrived in Ukraine before the invasion – but he never entered the game. For two years, he did not write any high-profile reports and almost stopped giving interviews.

Forgotten wars

Loiko was born in Moscow and studied to be an English teacher. He worked as a loader in the river port, a worker at a watch factory, and taught at a university. In 1988, he worked as an interpreter for Arnold Schwarzenegger on the set of the movie Red Heat. Through the same company that hired him to accompany the Hollywood star, he got a job as a translator at the Associated Press. That's how Loiko started writing and taking pictures. In 1993, the Los Angeles Times published his first war reports from Nagorno-Karabakh.

Generally speaking, it is not as difficult to survive in war as it seems, Loiko argues. It is more difficult if you are a reporter. The job forces you to take risks. This was the case in Tajikistan, in the Pamirs, when an editorial assignment required him to hit the road immediately: a tired driver fell asleep at the wheel and drove the car into a steep slope (the car turned over several times and stood on its wheels a few meters from a raging river). This was the case in the Afghan province of Panjshir, where Loiko found himself amid an unfriendly group of mujahideen. The journalist was pushed against a wall and shot at for five minutes, alternating in the air and under his feet (but then he was released). Or in Chechnya, when Loiko had to run out from under cover and wave someone down on the road to be picked up by an armored personnel carrier and taken away from sniper positions.

Loiko lists: Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, battles in Tbilisi, twice in Chechnya, armed clashes during the Romanian revolution... Like Márquez’s Colonel Aureliano Buendia in One Hundred Years of Solitude, who forgot how many wars he had participated in, Sergei Loiko struggles to recall the number of his own trips – either 20 or 25. However, unlike Buendia, who was tired of wars, in 2014, Loiko was getting ready for another one.

Right time, right place

The war in eastern Ukraine was both a high and a low point in Sergei Loiko's 30-year career. He states it as a fact: "Because of this war, I became famous – and lost everything."

In 2014, without journalistic accreditation, with only a sleeping bag, Loiko arrived in the village of Pisky, Donetsk Oblast. There, a column of Ukrainian armored personnel carriers was forming before being rushed to the already dilapidated Donetsk airport, where 200 Ukrainians were holding the line. Loiko persuaded the soldiers to take him with them. The trip continued to the drumbeat of bullets hitting the armor.

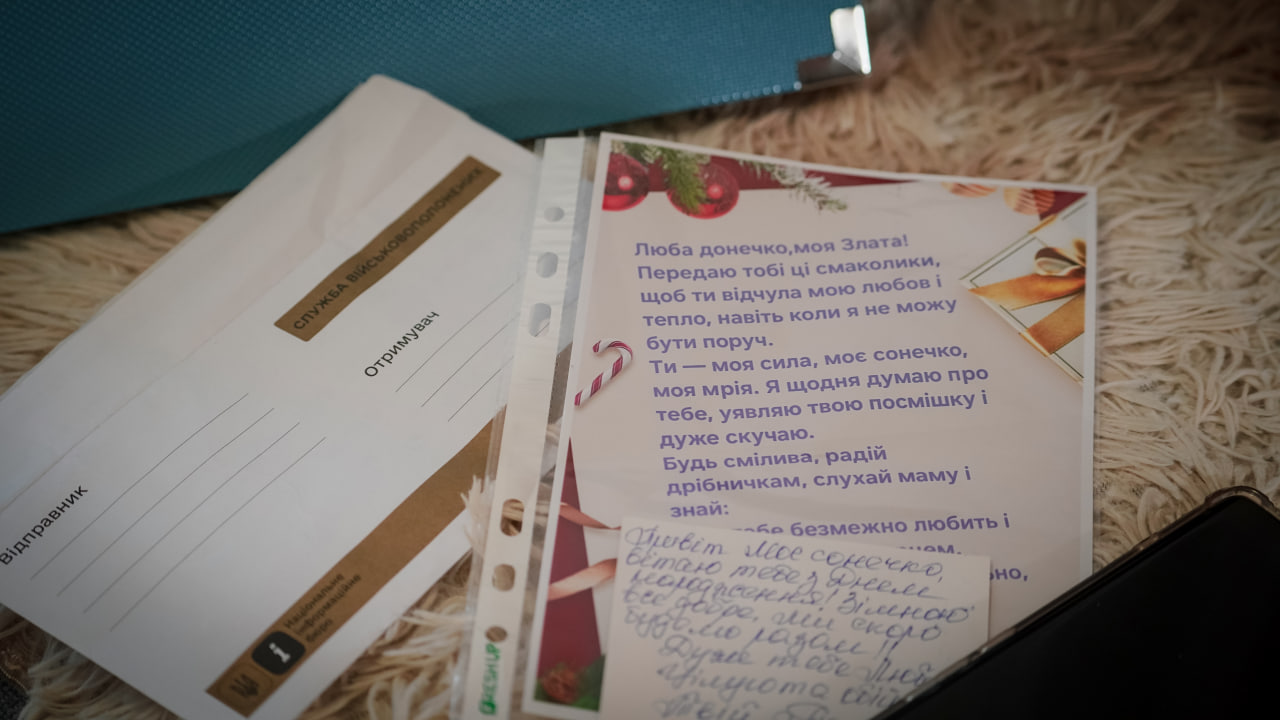

Loiko was the only foreign journalist at the airport, but for some defenders, he was primarily a Russian. He says that jokes, war stories, and the ability to work in a way that doesn't get in the way helped him become accepted. The most interesting – and, at the same time, the most difficult – part of a war correspondent's job, Loiko says, is talking to people. "They are always talkative because they know they could die any minute. The four days Loiko spent at the Donetsk airport with the "cyborgs" were like talking to suicide bombers – no one expected to get out alive. According to the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, 96 soldiers were killed (including five Heroes of Ukraine), four are considered missing (one of them is probably a traitor), and the remains of another soldier are being identified.

"Imagine," he says. "You're on the shore of Lake Kuusvesi in Finland, fishing. There are no other fishermen around. You are all alone. It's cynical, but I was happy to be in the right place at the right time and to be the only foreign reporter there. Later I regretted that I decided to get out and not spend more time with the cyborgs. But I wanted to save the footage, I was sure I would win a Pulitzer Prize.”

Loiko did not receive the award, but was honored with the Overseas Press Club's Bob Considine Award, the second most important prize after the Pulitzer. However, according to his colleagues at the Los Angeles Times, Loiko had ceased to be a journalist in Ukraine. In 2014, in an interview with the Echo of Moscow radio station, Loiko compared Russian soldiers to orcs. The American editorial board recognized such statements as unprofessional. As well as his texts, which no longer hid the author's sympathy for Ukrainian soldiers and hostility to the Russians.

Loiko says that the editors "neutered" his materials on Ukraine: they smoothed out the sharp edges and curbed the attacks on Russia. According to him, the editors knew that there were no "insurgents" in Donbas, but political correctness required them to call Russian soldiers “Russian-backed separatists”.

The editors stopped attributing Loiko's authorship in the articles, then suspended him for a year and eventually fired him during a large-scale staff reduction. In the parting remarks to him, he was told that his time in Ukraine had changed him as a journalist – and not for the better.

"Part of a war correspondent's job is to talk to people. They are always talkative because they know they could die any minute”

In the spring of 2014, Sergei Loiko was covering the battle for Slovyansk when his wife Anastasia was diagnosed with cancer. Upon his return, he took her to Israel for treatment, but by then, the doctors were powerless. After burying his wife, Loiko lost his fear and instinct of self-preservation. As one of his colleagues said, Sergei's photographs showed that "the author was seeking his own bullet" as he was shooting the battles at close range, almost on the line of fire. The first rule of a war reporter is to survive at all costs. Loiko began to neglect it.

In 2017, Loiko settled in Kyiv. After losing the LA Times audience, he took up writing novels (one of them, Airport, is currently being adapted into a movie script) and filming documentary series, but stopped publishing regularly in Western media. Loiko says that it was difficult to start working with another major outlet because of the stigma of being a “biased war correspondent”.

No place for old men

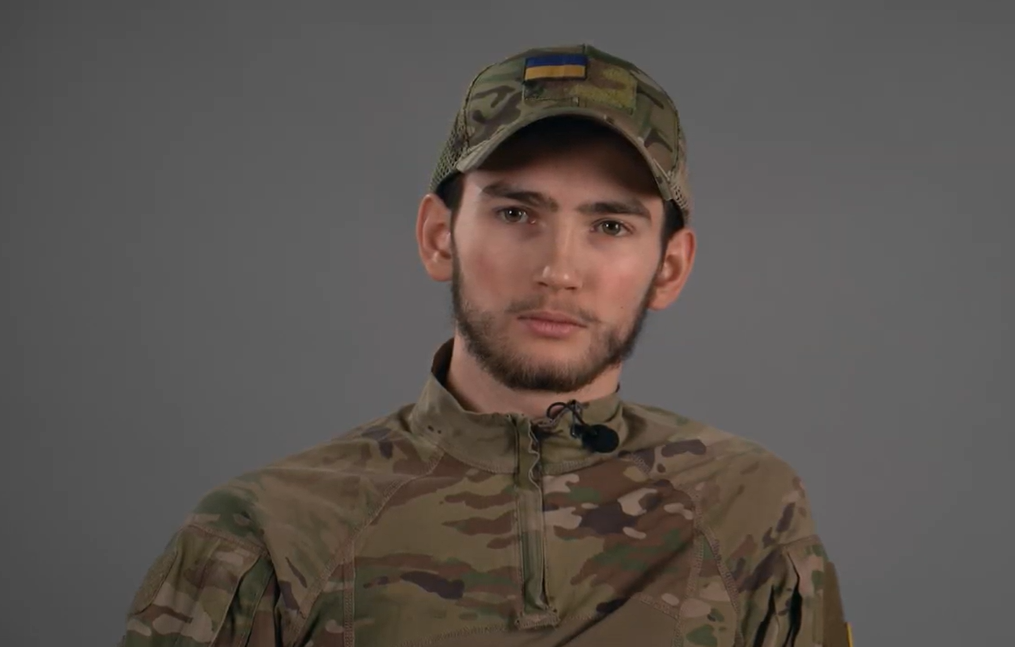

It is early March 2022, and Loiko takes off his glasses and smiles at the camera as he answers questions from a Voice of America journalist. He is in a state of poorly concealed euphoria, standing waist-deep in Ukrainian trench mud, his bulletproof vest peeking out from under his blue jacket, his wrists resting on an AK-47. He is 69 years old and already knows he has cancer. This is his first war not as a journalist, and he clearly likes this status.

On February 24, 2022, Loiko headed to the military registration and enlistment office in the Pecherskyi district of Kyiv. He came to pick up his weapon with a Russian passport, not an American one. As a counterbalance to his citizenship of the aggressor state, he brought with him the novel Airport, which is about "cyborgs." The book, Loiko says, became something like a visa application. When the military commissar saw the author's photo on the binding, he called upstairs and the "visa" was approved. He also found a commander who was a fan of the book and invited Loiko to join his brigade.

In 2022, a process that had already begun continued – the withering of the war correspondent in Loiko.

“I could not call any war I saw my own. The war in Ukraine is mine, and I had no right to be here as a suspended journalist. For the first time, I was happy to be a soldier and to be shooting at enemies I hate," he says.

"The good news was that Loiko was accepted to the territorial defense. The bad news was that Loiko himself realized that he was too old to fight. As a correspondent, he had seen too much of the war, as a soldier – three weeks in the mud, beastly cold, waiting, waiting, waiting. Days were spent digging trenches on the outskirts of Irpin and Brovary, feverishly reading the news and being bored.

Would Loiko have been able to shoot at the enemy if he had to? No one knows, but he was ready for this war before many of the other participants. Loiko said everything about Putin and his "orcs" back in 2014, and the worst of his predictions came true, so now he is taciturn, saying that “Russia must be defeated”.

But the war Loiko would have preferred to take part in happened when he had no energy left. Shortly after being mobilized, he resigned from the service. Now, once a month, Sergei Loiko goes to the front to take portraits of soldiers. However, he is no longer drawn to places like Chasiv Yar or Serebrianskyi Forest.

"I am 71 years old," says Loiko. "I have metastases in my lungs, I will probably die soon – I realized that I cannot stay on the front lines.”

He says he would like to die as a Ukrainian. In the summer of 2022, when a Ukrainian passport was promised to a Russian man, Alexander Nevzorov, who had never been near the front, Loiko turned to the head of the Office of the President of Ukraine, Andriy Yermak, and his advisor, Mykhailo Podoliak, with a request for Ukrainian citizenship. According to Loiko, Podolyak assured him that he would help, but never called him back (Life in War sent a request to the Presidential Office about Sergei Loiko’s citizenship application, but at the time of publication, we had not received a response).

Because of his beliefs, Loiko says, he lost everything. He once played like Luka Dončić, a basketball player with a strong sense of place. Now, just like before, Loiko sees where the ball is going and where he can pick it up. But he can’t catch it, because he watches the contest from the spectator's seat.