Timothy Snyder: ‘The idea that it is offensive to call a fascist a fascist is weird’

Timothy Snyder was one of the first public intellectuals to call the Russian regime fascist, and the war in Ukraine not just a local conflict, but an event that could reshape the political landscape of the world. Nataliya Gumenyuk asked him why he believes that this war is genocidal and why he is confident that Ukraine has saved the world from the nuclear threat. This conversation took place as part of the podcast When Everything Matters. Life in War is publishing an abridged excerpt.

_21-min.JPG)

_21-min.JPG)

This is your third visit to Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion. What have you learned this time as a historian?

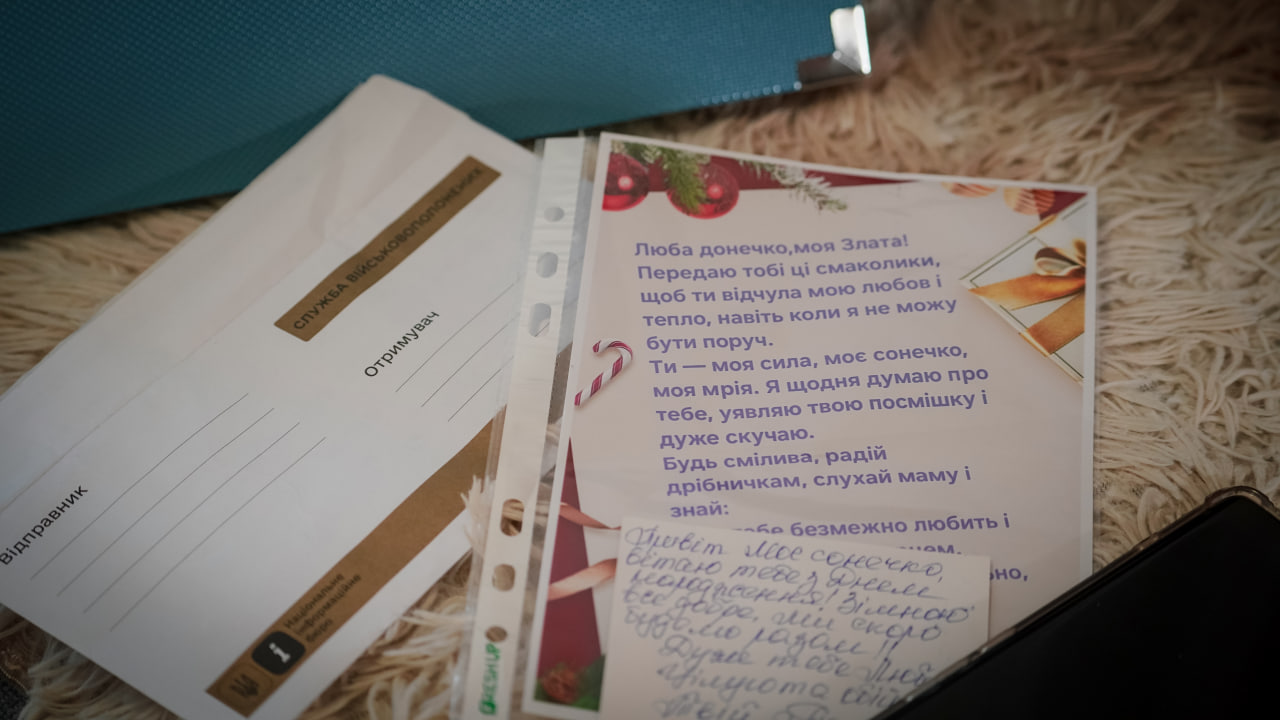

There are certain things that you understand very quickly when you're present even though you should have understood them before. On this trip one of those things has been the way that this war is about food now. I have been writing about that in an article in Foreign Affairs. But really I don't think I've quite processed how central it is to the whole thing.

As a historian of the Holodomor, this is something that should have been more on my mind. For the last 20 years, the Kremlin has been denying that the Holodomor happened very skillfully. When you deny a big crime it generally means that you're preparing to do that same sort of thing again. This should remind us that at the very top of their mind is the idea that food is a weapon of war.

The second thing that's really important in the background here is the significance of Ukrainian agriculture to the Ukrainian economy. When you understand how these are some of the most fertile soils in the world, you recognize that this is not just essential to the Ukrainian economy but it's part of a larger story of the world economy.

When you deny a big crime it generally means that you're preparing to do that same sort of thing again

Russia is trying to make sure that Ukraine can't sustain its own economy. But also what you see is that this war is fundamentally about a kind of reverse blockade of the world. Ukraine is being blockaded by Russia to hurt Ukraine but it's actually the world that's been blockaded because Ukraine feeds so much of the world. That's something that has become clear to me on this trip.

You were one of the first who clearly marked the current Russian regime as fascist. Why is Russian autocracy fascism? Do you see there is more acceptance of this in the world?

Starting with the definition: it's hard to create an academic definition of fascism because the whole point of fascism is that you reject reason in favor of will. So with fascism you're looking for leaders, propaganda systems, people who seem to be rejecting standard forms of logic and empirical evidence in favor of a commitment to will and ability to place their belief not in what's happening in the world but in the mind of a leader.

A second element of fascism is the idea that you don't understand the world in terms of objective forces and interests. You understand the world in terms of conspiracies. So the international Jewish conspiracy is one. The idea that Ukraine only exists because of a conspiracy is in my view a fascist idea.

A third part of it is the notion that since everything is about will and not reason, and since the world's about conspiracies and not interests, the way to pursue foreign relations is by way of

force. We, [fascists], are just going to try to overwhelm our enemies with our propaganda and with our bullets.

The war in Ukraine is allegedly about gays, Nazis, and Jews

The Russian war in Ukraine is very much like that. There is no coherent Russian explanation of why they're at war with Ukraine, and why this would serve Russian interests. In any rational account, you can't really justify this war. What they're doing is they're producing deeper and deeper levels of irrationality about what they are doing. It's about gays, it's about Nazis, it's about Jews, it's about Satanists – whatever.

The word “fascism” is contaminated in a whole bunch of different ways. One of them is that Russia itself refers to its enemies as fascists all the time. That makes everything so confusing and it discourages people from using the word. So prime Russian fascists like say [philosopher and political theorist Aleskandr] Dugin always refer to liberals as fascists.

There's also a sort of lack of confidence. People know that saying someone is a fascist is a big claim. So they prefer to say “authoritarian” or whatever. Another weird thing which is going on in – this particular to the US – is that people don't like to use the word fascist because they think other people will be offended. The idea that you should be offended that you're calling a fascist a fascist seems very weird to me.

You mentioned that the term “fascism” is contaminated. Another concern is that the term genocide is contaminated. The lawyers, of course, would say “let's be cautious – it's very difficult to prove.”

Not at all. I think it's a really clear call. Perversely, the problem that people have is that they know it's genocide. Because people know it's genocide, they don't want to call it genocide.

That's the logical reason because if you know it's genocide that means you should be doing more than you're doing. I think that's the moral trap that people are in. It applies to governments in the sense that if a government issues an official statement along the lines of “there is genocide” that suggests that the government probably should be doing more. That is the case with the United States of America. In our own official discussion I know that's happening. But it's also true for human rights activists and people in general. If it's true that this is genocide that means that we should have been engaged more.

The idea that you should be offended that you're calling a fascist a fascist seems very weird to me

In my academic work, I don't use the word genocide because it has two meanings. The one meaning is the kind of popular meaning: genocide means killing everybody. And then there's the legal definition from the 1948 [UN] Convention which involves an intention and five separate acts with that intention. But when we're considering what's happening in Ukraine in terms of the legal definition, it's unambiguous that there is intention.

_09_-min.JPG)

There has never been more intention expressed in public in any historical genocide. There's far more obvious expression recorded, obvious expression of genocidal intent here. On Russian state propaganda, in the statements of people who are high up in the Russian state, all the way up to the president of the Russian Federation, they're very clear statements of intention involving the claim that Ukrainians don't really exist, for example. Or just open claims that people who identify as Ukrainian should be killed in the millions.

And then all of the acts in the Genocide Convention: from killing people which is the first one down to the last one which is the forcible removal of children – all of those things have been clearly fulfilled. So I think it's pretty transparent that this is genocide. What we're really dealing with is not the question of whether this is genocide. What we're dealing with is a very familiar historical phenomenon which is that simple factual knowledge of something like this is not enough. It has to involve a kind of moral reflection.

This war is called an imperialist war. Is it really so? Can Russia be an empire in the XXI century?

Of course, empire and fascism are related. Since the XX century, fascism is a kind of neo-empire. Fascists are often people who think that we need to restore an empire or we need to catch up with somebody else's empire. So fascism and a kind of neo-imperialism can go together. That this is an imperial war is obvious.

There has never been more intention expressed in public in any historical genocide as there is in Russian propaganda

What's more specific and useful is to describe it as a colonial war. In the sense that many Russians understand the Ukrainians as being a colonial people in the sense that “they want to be ruled by us”. It's a very specific kind of understanding. You can have an empire without thinking that but to imagine that the Ukrainians are colonial people: they really are us or they really are our little brother they may not know it but that's who they really are. That's a very widespread belief unfortunately in Russia and it's part of the official justification of this war. Namely that the people who run the Ukrainian state are some kind of thin stratum of westernized or Germanized or Polonized or Europeanized or some kind of artificial thin straum, and if we just get rid of those people then the Ukrainian masses will subjugate themselves to us willingly. So in that sense it's a colonial war because it's about seeing other people as a people that want to be colonized or are ready to be colonized who are not really we're not really subjects in the world.

I think it is pretty important for the history of Russian imperialism to be taught alongside the history of other imperialisms. I think making an exception for Russia where somehow the Russian Empire is legitimate and other empires are not legitimate is one of the weirder moves that one finds.

Should we look for the positive in the war? Indeed, wars help to develop. But I also have fears that despite the attempts to find the positive, such as the fact that Ukraine has become stronger and people have become more united, threats still exist.

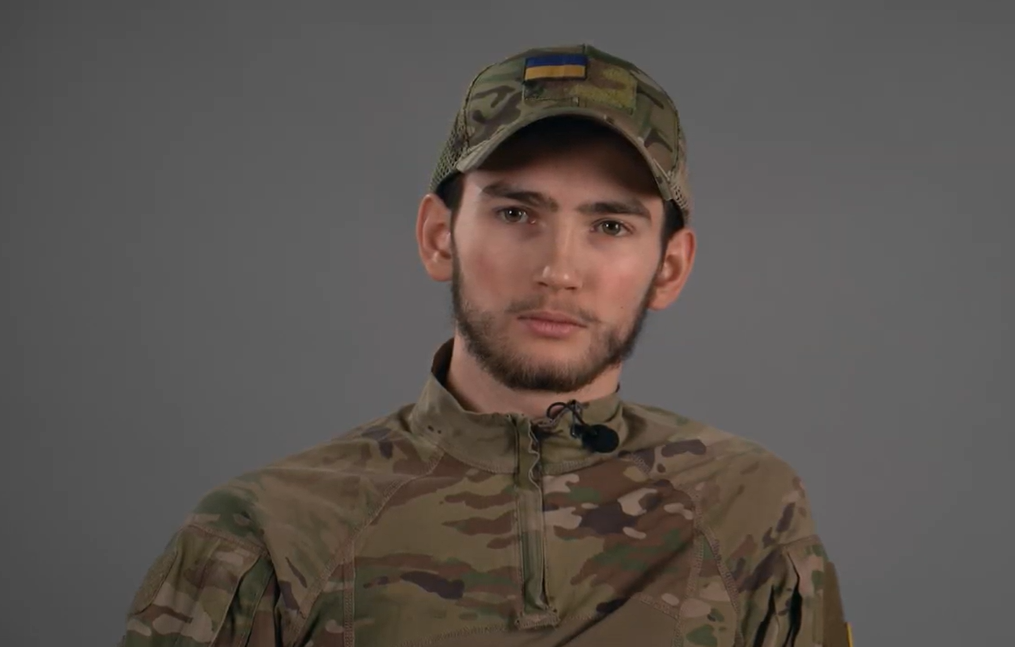

I'm concerned about the loss of the best people. Maybe that's not the best way to put it but Russia's fighting this war primarily with people who have less of a choice. They're fighting this war with the people that they forced to fight it from occupied Ukrainian territories. They're fighting this war with their own people they've taken out of their own prisons, they're fighting this war with their national minorities, they're fighting this war with with the impoverished. There are very few Russians who see this war as their own war in the sense of they want to go off and fight it.

The Ukrainian army is much more socially representative than the Russian armed forces. I worry about too many Ukrainians dying. I worry about too many Ukrainians dying who have a future in this country where they would be building and doing interesting things.

I think it is pretty important for the history of Russian imperialism to be taught alongside the history of other imperialisms. I think making an exception for Russia is one of the weirder moves

Another thing I worry about is the difficulty of getting from a wartime politics to post-war politics. I would say that you have an excellent wartime leadership. The people who were elected for peacetime – or even elected like Zelenskyy on a peace platform – basically have proven to be excellent wartime leaders. But for Ukrainian democracy to continue, those excellent wartime leaders have to be willing to make the step to be excellent peacetime leaders. It really is a different sort of job and it involves having different courts of authority. I think it's possible, it's been done. If you are a wartime president you have to be aware: this is a state of exception and at some point I'm going to return to something else.

_25%20(1)-min.JPG)

Another concern which I have is about [post-war] reconstruction. However much money or however many resources the West throws into reconstruction it would be a moral hazard and a mistake to put all of those resources in the center of the Ukrainian state. It's my strong conviction that we need to be thinking about the oblasts and the towns but also the Ukrainian NGOs and make make sure that reconstruction is done in such a way that we're not creating a moral hazard at the center of the Ukrainian state.

It would be a mistake to hand over all the resources for reconstruction to the center of the Ukrainian state

To end on the positive, one thing in your question that I would disagree with is that there is no positive in the war. People who go through wars almost never say, “We're fighting this war because we are trying to preserve the status quo”. Generally when people fight wars, they're fighting wars on behalf of a society that they want to see be better than it actually is. Nobody goes to war for wealth inequality and corruption. Nobody says “I want to lay down my life so other people's kids can have a better chance than my kids”, right? So war in that sense does give a chance for reform.

I recently read an essay by the philosopher Vasyl Cherepanyn. He wrote that in talking about post-war reconstruction, there is a temptation to avoid the complex reality of the present. Instead of providing weapons to Ukraine right now, they talk about rebuilding later. Can there be a balance between the former and the latter?

The analogy I would use would be a house and its roof. We build a house and it has walls and it has doors and it has windows but it doesn't have a roof. We say, “Look at our beautiful house, it's done, it's great”. And then there's a rainstorm or a snowstorm or a hailstorm – and our house is ruined. And then we say, “Okay, now it's time for reconstruction”. But it probably would have been better to build a roof and that's how I feel about air defense. So all of the Ukrainian cities need better air defense and that can be provided frankly at trivial expense compared to the cost of reconstruction. I agree with the formulation that Ukrainian military aid is humanitarian aid because it is a way of making sure that there's less destruction in Ukraine.

Washington is no longer afraid of nuclear escalation. The United States no longer panics that Russia might strike with nuclear missiles. How did this happen?

On the nuclear issue I should have mentioned that earlier when I was talking about all the things that you have done for us. This just doesn't get said often enough, to recognize that what Ukraine has done is reduced the worldwide risk of nuclear war considerably. Because what the Russians tried in this war was nuclear blackmail. What they tried was to say it's okay to invade another country so long as you have nuclear weapons and threaten to use them. And they almost got away with that. A lot of people thought that was a plausible argument.

Soldiers never say “We're fighting this war because we are trying to preserve the status quo”. Nobody goes to war to defend corruption

You heard all this nonsense about how countries with nuclear weapons have never lost a war and can't lose wars. Of course, that's completely idiotic. Countries with nuclear weapons lose wars all the time – they generally lose the wars that they start. Nuclear weapons did not save the British Empire, they did not save the French Empire, they did not save the Americans in Vietnam or in Iraq or in Syria. For that matter they did not save the the Soviets in Afghanistan. Nuclear powers regularly lose wars.

So there was this big nuclear bluff. If Ukrainians had accepted that nuclear bluff that would have made nuclear war much more likely in the rest of the world. Because if you're allowed to do whatever you want by just having nuclear weapons and then saying things that would mean that everybody would want nuclear weapons.

The Biden administration's starting point was: “We're going to help Ukraine but we're not going to fight a war with Russia”. It's taken a long time for them – and then the Russians of course took the second part as a resource and have spent a lot of energy trying to explain to the Americans that whatever they do it's a war with Russia. The Americans in their slow way have tried to process all of that. All that's happened is that they've processed it and they've now realized that that was never actually true.

But you're not going to find American officials who say that. You're not going to find American officials on the record who are going to say: “Yeah we got this wrong for a year” because American officials never say they got anything wrong – let alone for a year.

Why are the Russians unlikely will use nuclear weapons?

Because it's a prestige for Russia. For Russia much more important than Crimea or the Donbas or Ukraine or any of this stuff is the notion that they're a superpower. And the notion that they're a superpower depends upon having nuclear weapons and not using them.

The moment that you use a nuclear weapon, one: you're admitting that you lost a conventional war therefore you can't be a superpower. Two: you are are becoming a criminal and you're upsetting everybody, including your allies, the Chinese. And three: you're taking away your own power to try to intimidate people with a threat of weapons. Because if you use the weapon you can no longer threaten people with it.

Photo: Yurko Dyachyshyn