Fertilization with preserved sperm. Why wives of fallen soldiers hesitate

Soldiers cryopreserve their semen so that their wives can be fertilized in the event of their death. However, after the passing of their husbands, women face many ethical and legal barriers. A Life in War journalist talked to an Israeli woman who used a soldier's posthumously collected sperm and a Ukrainian woman who is currently deciding whether she should give birth to a child from her late husband.

Since the outbreak of full-scale war, about 700 soldiers have had their sperm cryopreserved at the Stefan Khmil clinics in Lviv and Ternopil and at the ICSI laboratory in Kyiv. Before the war, the demand for this service was three to four times lower.

Sperm inheritance

According to medical lawyer Nataliya Lisnevska, about 200 servicemen come to her for advice on the legal basis of cryopreservation every month. Lisnevska explains the large number of clients by the fact that until 2024, there was no law in Ukraine that clearly regulated the inheritance of reproductive cells, and most soldiers did not know which document would be legally binding.

To name a wife, girlfriend, parents, or other relatives as the heir to their reproductive cells, men signed a power of attorney with the clinic. But in the event of their death, the document would become invalid. At the same time, it was problematic to specify sperm as an inheritance in a will, because biomaterial is not classified as movable or immovable property. Until March 2024, it was unclear which document – a power of attorney, an order, or a will – would be valid after death.

In addition, Lisnevska says, the servicemen were concerned that in January the Verkhovna Rada amended bill No. 10448 on the preservation of Ukraine's gene pool, including a proposal to utilize sperm from fallen soldiers. At that time, medical lawyer Olena Babych criticized the bill in a Facebook post, noting that MPs were worried about the "financial component of cryopreservation," probably meaning that the government did not want to pay benefits to children born of the biomaterial of the dead.

The amendment was later repealed. On March 12, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed the amended bill, according to which heirs can use the biomaterial even if the donor dies, and the will of the person notarized before the law came into force does not become void. The state will pay for the storage of cells for three years in the event of a serviceman's death.

However, only the storage is paid for, and the serviceman or servicewoman (who wants to preserve eggs) must pay for the collection and preparation of biomaterial for conservation on their own. For men, the procedure will cost from 2,500 to 4,000 hryvnias ($62-99), and for women from 8,000 to 15,000 hryvnias ($197-369). In addition, egg retrieval involves more manipulations than the collection of the semen. Before that, a woman needs to undergo anesthesia (3,000-4,000 hryvnias ($78-99)) and undergo a course of medical ovarian stimulation (3,000-7,000 hryvnias ($78-172)). However, some clinics offer discounts for service members or do not charge them at all.

Information campaign

Private clinic workers interviewed by Life in War believe that they would have more clients if the state conducted a large-scale information campaign on cryopreservation of biomaterial and doctors informed mobilized people that they had this option during military medical examinations.

For example, in the United States, information about the possibility of storing sperm and eggs is part of the Soldier Readiness Process Training program. Soldiers are given detailed questionnaires in which they indicate how to use their cells in the event of death or injury. In Israel, the army offers soldiers either to preserve their semen in advance or to sign a permission that in case of their death the biomaterial will be taken posthumously and given to the widow.

The information campaign is also needed because not all soldiers are aware of how the harsh conditions at the front affect fertility. Doctors advise soldiers to cryopreserve the material in advance, because due to injuries, trauma to the genitals, and exposure to chemical weapons (as of March 2024, the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine reported 1,068 cases of Russian use of chemical weapons), fertility can decrease. Injuries to the groin and genitals are not uncommon: according to urologist and military rehabilitation specialist Ivan Dmytryk, about 7,000 Ukrainian soldiers have suffered reproductive trauma.

What Ukrainians think about cryopreservation

At the request of the Public Interest Journalism Lab and Life in War, the Kharkiv Institute for Social Research conducted panel interviews: three focus groups with military personnel and relatives of the deceased military, as well as five in-depth interviews with the wives of soldiers about their awareness of the procedure of cryopreservation of semen. According to the researchers, "the level of awareness of the military and their families regarding the use of modern reproductive technologies is rather limited."

To find out why society condemns parents who are planning or have already had a child from a dead soldier, Life in War spoke to two women: an Israeli woman who used the sperm of a soldier who was taken posthumously and believes that she showed solidarity with him, and a Ukrainian woman who, despite her sense of duty to her late husband, is afraid to give birth.

After learning about cryopreservation, respondents said they saw several barriers to popularizing the procedure in Ukraine. Among them, the respondents mentioned the financial inability to pay for the procedure and provide for a child in the future, the shortage of cryobanks in Ukraine, distrust of doctors and fears that the biomaterial will end up on the black market, and a large number of wounded service members who do not want to become parents after being injured.

However, the majority of respondents said they would support a state program to store soldiers’ biomaterial, noting that it is necessary to preserve the country's gene pool. Life in War publishes several quotes from the interview.

"I really like this idea. I support it, and I'm glad that attention has been drawn to the amendment [about the utilization of biomaterial in case of death of a serviceman or servicewoman]. This is about preserving our gene pool. They [the military] can easily catch a cold and lose their reproductive function. [With pre-cryopreserved biomaterial, the family will have a chance to raise a child and have it at the time they want."

"I believe that the state can offer to provide such a service at the state level. These are our future generations that will be stored there [in the cryobank]. We know that the birth rate in Ukraine has fallen dramatically. This will entail a reduction in educational institutions, a reduction in jobs, and, in principle, the population of Ukraine. That's why I'm in favor of it."

"The state should take care of this, at least for a certain period. We understand that the war will not be endless, and the state should take care of [the preservation of the gene pool] during this period."

"The state should do something for girls who are also fighting there [at the front] alongside boys. They get cold, are freezing, and their ovaries can fail. But her [cryopreserved] egg has been stored, so she can become a mother."

"The state should provide the possibility of freezing. I know that even contusion has a bad effect on procreation. [If you have cryopreserved biomaterial], you can return from the war and use it. All this should be at public expense, the state should be interested."

"If a military family has such a need, I think that this [cryopreservation of reproductive cells] should be in the law of Ukraine."

"I think it's pointless. Why would a woman give birth to this child? What on earth for? In memory of her dead husband? How will the stepfather treat this child?"

The sociologists also asked what needs to be done to ensure that all military personnel are aware of the possibility of cryopreservation. The respondents indicated that the problem was the lack of information.

"[We need] explanatory work, information activities. What the advantages [of the procedure] are, what the disadvantages are, and what the dangers are. I think that some papers should be written very competently, like for organ donation."

"I think that those [military] who are already there [in the combat zone] should be informed through their superiors. They should inform them that there is such a program, and whoever wants to can go and donate [biomaterial] on such and such days."

"If it is properly presented to society, it will accept [information about the importance of the procedure]."

Although most respondents said they supported cryopreservation, some were concerned that the biomaterial could end up on the black market.

"[I am worried] that the material will be misused. We can only count on decency here. This topic should be legally protected. Maybe some insurance policies, some compensation."

"There should be guarantees that it [biomaterial] will not be used anywhere without your knowledge. That is, complete transparency."

Ethical barriers faced by parents

In 1975, Italian Roberto Casali was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Immediately afterward, Roberto's wife Kim, a famous artist and author of the comic book Love is..., persuaded him to preserve his sperm. A year later, her husband passed away. After another 16 months, Kim gave birth to the world's first child conceived after the death of one of their parents. Milo Casali, whom the press called a “miracle baby”, never said how he felt about the circumstances under which he was born, and in general, if he gave comments to journalists, it was more about his work as Milo became one of the designers of the famous video game Doom.

It is not known how many children in the world were born as a result of fertilization after the death of a father or mother. This practice is obviously not widespread around the world as each case still attracts media attention. Journalists are particularly interested in the ethical aspect: is the decision of a mother who deliberately deprives her child of the opportunity to see their own father at least once fair? Unlike Milo Casali, 25-year-old Englishman Liam Blood, another famous boy born as a result of posthumous insemination, did not avoid talking about this topic. "I almost think it would seem a bit strange to have a dad around," he once said.

In Ukraine, fertilization with a man's sperm after his death was not possible until recently due to legal obstacles. Women generally approve of the possibility of conceiving with preserved sperm. In a sociological survey commissioned by Life in War (see above), only one out of five wives of servicemen expressed negative views on posthumous insemination, and this was because of ethical concerns.

What are the reasons why widows are hesitant to accept insemination with preserved sperm? And what can convince them of the acceptability or unacceptability of such a decision? In particular, the editors talked about this with an Israeli woman who used a soldier's sperm that was collected posthumously and a Ukrainian woman, the wife of a fallen soldier, who has the option of posthumous insemination but is currently unsure whether she should use it.

Nadiya Lytovchenko

36, Ukrainian citizen, designer, until 2024 could not use the cryopreserved sperm of her husband who died in the war.

In 2015-2016, my husband Andriy Lytovchenko and I spent two rotations between Bakhmut and Mayorsk as part of the ASAP Rescue Group team. I am a paramedic, he is a driver.

During this period, our colleague, the chief medical officer of the 93rd Brigade, lost her fiancé. She told me she regrets a lot that they had not had a baby or cryopreserved their reproductive cells in advance. Despite the traumatic event, she still wanted to have a child from her deceased lover, and the fact that she was unable to do so stuck in my mind for a long time. Her story also stuck in my husband's mind. He always knew that a full-scale war was ahead. So we decided to cryopreserve his biomaterial in one of the Kyiv clinics.

In 2017, my husband was offered a job in Marseille, and we moved, but we agreed that if the war started, we would return. In 2020, we started preparing for the birth of a child, and in March of the following year, we had a son, Mark, born naturally. But just in case, we continued to pay for sperm storage at the clinic.

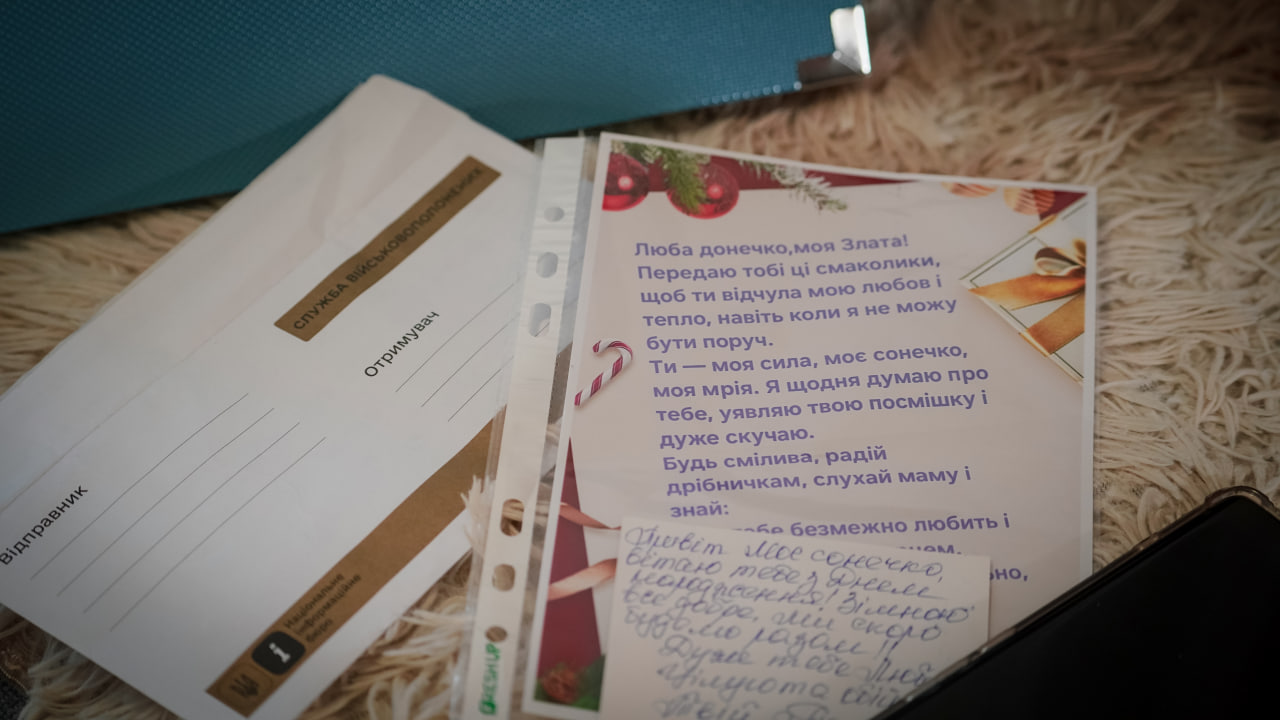

Andriy fulfilled his part of the promise – he returned to Ukraine. I, for obvious reasons, did not. In July 2022, Andriy, already a platoon commander in the Territorial Defense Forces, was ambushed with his brothers-in-arms near Dementiyivka, Kharkiv Oblast. We had been married for eight years.

At first, I planned – now I realize that it was somewhat impulsive – to immediately use my husband's reproductive cells. My husband always dreamed of having what he called a "gang": he wanted two kids. It was eating away at me. For the first year, I convinced myself that I had to use his biomaterial and give birth to a second child in his memory: "Dad didn't live in vain. He has a little copy." I realize that this sounds very trite, but the opportunity to have a child from a deceased loved one still seems like a miracle to me.

When Andriy died, I felt a mixture of guilt and duty. The thing is that the stages of grieving do not always follow one another: one moment there is a period of acute grief, and the next there is a phase of reconciliation with the fact of death. Often these periods can alternate. Grief has a chaotic trajectory. When the emotions subside, you realize that the decision to have a child must be made with a cool head.

A child born of a deceased person is an [ethical] paradox. On the one hand, the child has no father because of the war, and on the other hand, because of the mother, because of me, who decided to give birth despite the death of my husband. I am the only one who makes the decision whether to give birth to a child from a dead husband. And I will have to deal with the consequences alone.

To hear a child say, "I didn't ask you to give birth to me from a man who is no longer alive," is scary. Explaining to my son Mark what happened to Andriy is one thing. Explaining to a hypothetical future child who was born from the sperm of a dead man is another. It seems to me that these are two very different conversations, and I can't even imagine what they will be like.

I'm already thinking that there will be competition between Mark and his possible sibling. Mark has a photo with his dad, but the hypothetical child does not. Mark, even though he doesn't remember, has seen his father, and has spent a small part of his life with him, while the hypothetical child is deprived of this.

As it turned out, I had no right to use my husband's reproductive cells, because the power of attorney issued by the clinic expired after the principal's death. To use the material, I needed a will, and we hadn't foreseen this. So I just paid for the storage of the biomaterial and waited for the legislators to pass all the amendments. In the fall, the government passed a new bill that will eliminate most legal conflicts. And I will be able to use Andriy's cells. I haven't decided whether I will do it yet.

To hear a child say, "I didn't ask you to give birth to me from a man who is no longer alive," is scary

I interviewed 20 women I know who have lost a partner. About 40% said they regretted not saving their partner's sperm. Often because they did not know about the procedure. In the two years of war, there should have been a larger awareness campaign. Why aren't guys informed about the possibility of cryopreservation when they undergo a military medical examination? Waiting for the state to take the initiative is short-sighted.

People avoid the topic and laugh it off. When I talk to girlfriends or wives of servicemen, their partners sometimes react aggressively. They tell me that I have a "widow's trail" behind me, as if I am putting the idea in women's heads that their husbands will die. I don't say that, but my Andriy was planning to return home, too. All I'm trying to do is help people to be safe than sorry because lost hope is much worse than an unused opportunity.

Irina Axelrod

50, an employee of a water filter factory, mother of Israel's second child conceived from the sperm of a soldier whose biomaterial was extracted posthumously.

I did not know the father of my child. I learned everything I know about him later. German [Rozhkov] emigrated to Israel from Ukraine in the late 1990s with his mother, Liudmyla. On March 12, 2002, Israeli army officers informed Liudmyla that German had been killed in the city of Qiryat Shemona, where he had engaged in a 30-minute firefight with Hezbollah militants. Five civilians were killed along with him. He was 25 years old.

Approximately 48 hours after his death, at the request of his mother, sperm was extracted from his genitals and preserved in liquid oxygen. He became the second Israeli soldier to undergo a posthumous sperm retrieval operation [the first was Kivan Cohen, who was killed by a sniper bullet while on a combat mission in the Gaza Strip - ed.]

I found out about German ten years after his death on Yom HaZikaron, the Day of Remembrance for those who died in Israel's wars. At the time, my friend told me about Liudmyla and that she had cryopreserved her son's biomaterial. I already had a child from my ex-husband, but I wanted another. I was given Liudmyla's number, called her and offered to bear her granddaughter for her. A month later, she called and said yes.

Through conversations with Liudmyla, I learned more and more about German, the kind of person he was. He became the father of my child. But did he become a close person to me, did I start to feel something for him after I learned almost everything about his life? After all, you have to get attached to living people, not dead ones.

The use of biomaterial from a deceased person does not seem strange to me. On the contrary, I was interested in participating in something so unusual. My decision was driven by my personal interest in having a child and solidarity. When I heard about Liudmyla, and that her son had died defending the country, I felt sorry for her. She was alone, all her relatives were abroad. This was my way of helping. In addition, this is a solution for mothers who cannot raise their children on their own due to financial problems.

I had a condition: I would not be a surrogate mother who would give birth to a child and disappear from their life. Many journalists make a mistake and write about me as a surrogate mother. I am just a mother.

It took us four years to get a court order to use cryopreserved biomaterial. Our situation was very unusual as the Israeli judicial system had never encountered such cases. Eventually, in February 2016, the judge granted permission, [commenting on the decision as follows: "When the law does not provide an answer, the court must turn to the principles of Jewish heritage. "Give me children, or else I die!" our mother Rachel shouted... We are told: 'Be fruitful and multiply'." In February, we received permission to use biomaterial, and on April 8, 2016, we used the artificial insemination procedure.

My daughter Veronica became the second child in Israel born from the sperm of a fallen soldier. I used to think that she was the first, but the documentary filmmakers who made a movie about us said that another girl had been born earlier. As far as I know, there are about a dozen such children. [Cryopreservation is being used by more and more relatives of the dead: after the recent clashes with Hamas, sperm was taken from 91 soldiers – ed.]

My daughter became the second child in Israel born from the sperm of a fallen soldier

In Israel, there are discussions about parents of the deceased using surrogate mothers to raise their grandchildren on their own. Some people say that these children are living monuments erected to the dead, a way to fill the void after a loss. I don't think so. I don't think Veronica was born in memory of anyone. She was born not to remind, but to bring joy.

Veronica knows that her father is dead. But she doesn't know how he died or how she was born. When the time comes, we will talk. We have a documentary,and clippings from articles about her birth. We will show her that. I don't think it will upset her that she was born to a hero who died. In our country, this is normal. Besides, it's a respectable thing as she became the transmitter of the family lineage. Veronica has her father's surname, not mine. After the death of German and Liudmyla, the Rozhkov family would have ceased if it weren't for her.