"Our survival in combat determines who we return as"

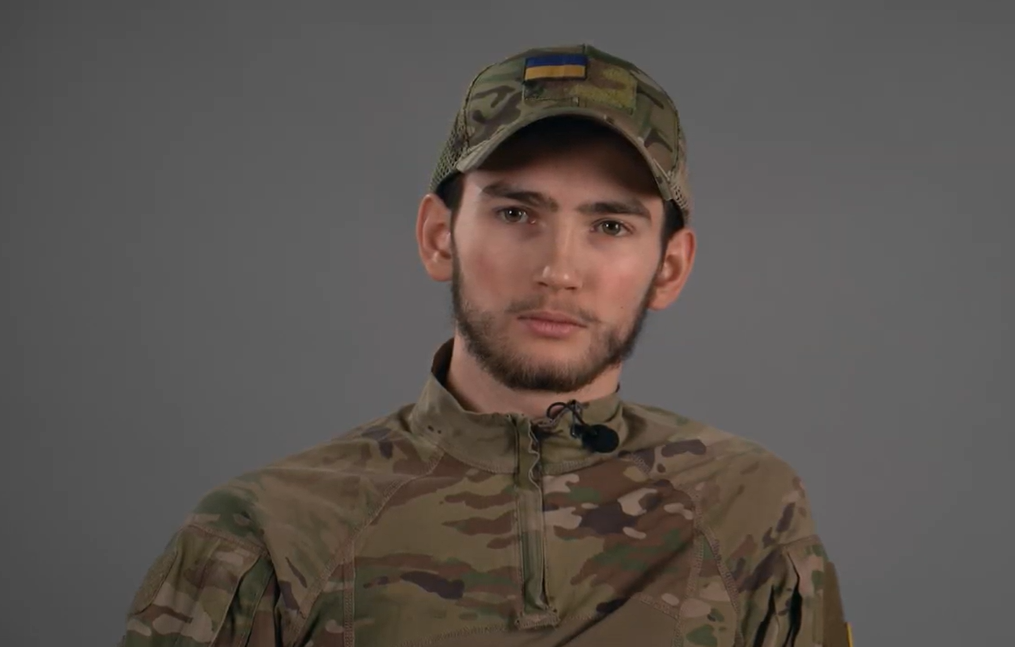

Before the war, Yevhen Shybalov worked as a journalist and was a correspondent for Dzerkalo Tyzhnia in Donetsk. In 2014, he left the profession to provide humanitarian aid to IDPs from Donbas. In February 2022, he became a volunteer, liberating Kyiv Oblast. He fought in the east as a grenade launcher operator in the 241st Separate Brigade of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. He was captured and spent six months in captivity. Yevhen Shybalov thinks of the war as a lottery, where survival is not guaranteed, but following certain rules increases your chances. In a conversation with Life in War, he tells us what habits he acquired during his service, how real combat differs from battles in movies, what annoys the soldiers in civilian life, and why helicopters constantly feature in his nightmares.

In the interview series "Hard Memories", the editors talk to servicemen and women about their personal experiences related to the war and the difficulties they face in civilian life. Videos of the conversations are available on the Life in War YouTube channel.

On life before the full-scale invasion

I have three brothers and three sisters. There are seven of us in total, and I am the oldest. Being the eldest brother in a large family means that you often have to take over for parents who work hard to support so many children. Very quickly, you equate the concepts of "love" and "responsibility". Perhaps this is not always correct. Some people think it's hyper-protection. But this is my lifelong habit.

For example, when I started humanitarian work, I felt responsible for the people in eastern Ukraine, among whom I grew up and spent my life. When I joined the army, I felt responsible for every person in the country.

It so happened that I changed my profession twice in my life, and both times because of the war. In 2014, I left journalism and became a humanitarian worker. I helped civilians affected by the war in Donbas.

It all started when refugees from Snizhne came and settled in the student dormitories of Donetsk University, because there were battles near their town – at Savur-Mohyla. Now everyone is trained, they know what a go-bag is, but back then, people were just running away from the war – they came without taking anything with them. Especially well I remember a woman who arrived in her home robe and one slipper because she had lost the other on the way. Then my brother and I, along with a few friends, did what any normal person would do in our place. We simply collected whatever was in our pockets, went to the supermarket, and bought them the least we could: food, water, and diapers. And these people started passing our phone numbers to their fellow sufferers. Very soon we realized that either we stop doing this, or we make it our new profession.

I was engaged in humanitarian work until 2022. Initially, my task was to involve the UN, the Red Cross, and other major players in eastern Ukraine – in the early summer of 2014, they were afraid to enter Donbas for security reasons. So I did everything in my power to mitigate the suffering of civilians in eastern Ukraine. And I also did everything I could to bring peace closer, because I believed until the last that it was possible through non-military means. That it was possible through diplomacy, negotiations, dialogue, compromises, etc. But February 24, 2022, proved that I was very much wrong about this because, in the end, everything turned into a full-scale war. And on the first day of this war, I volunteered to join the Armed Forces of Ukraine. As a person who had never served and had no military experience. Of course, to become an infantry soldier.

On surviving the war

My call sign is Moose. In the first days of the war, we had neither uniforms nor basic winter clothes. Kyiv residents gave us warm clothes. I got a hat with a print of a fun cartoon moose on it. At the end of the day, none of my fellows called me anything else.

I naively thought that I was a little better prepared for the war than most of the guys who volunteered. I lived in Donetsk and came under fire there. I thought I was morally better prepared for the war in some ways. But the risk of becoming an accidental victim is one thing. But when you are actually a target, it's quite another.

A person who seemingly had some intense situations in their peaceful life never knows how they will behave in combat. Because there are some deep instinctive reactions at play that are impossible to predict. That is, until a person has been in combat, they do not know what kind of soldier they are.

The first to die in war is the lazy one. The one who is too lazy to do everything properly. He is too lazy to dig in properly, too lazy to choose a position – he entrenches himself wherever the ground is softer, not where it is appropriate. Such soldiers are often too lazy to wear body armor, too lazy to check if their radio is charged, and too lazy to clean their weapons. I saw an entire platoon forced to retreat and suffer losses on the way out just because the guys' assault rifles jammed. They were clogged with dirt. These are all seemingly simple things, but it is often the simplest things that make the difference between life and death in war.

When you are actually at war, you do not see the war. You either hear it or feel it. If a person is lying face down in a trench, then only one part of his body is looking out. So for me now, "feeling with my ass" is a very literal expression.

The war itself even has a kind of adrenaline high. People on the front line, whenever they talk to each other, always have these silly smiles on their faces, as if they are having a lot of fun. I consciously understood that it was just adrenaline; it shakes everyone up. But from the outside, it looks like, firstly, the guys are really enjoying it, and secondly, it's clear that they've already gone a little crazy. But the only way to survive it all is to fall into this state of adrenaline intoxication.

Once a rocket from a helicopter hit my position right in the trench. Two guys were killed. I had to pack one of them in a sleeping bag to take at least something out and give it to his family for burial. It was a very tough experience. Later, I revisited this scene in my nightmares. But right then, I experienced emotional paralysis. I had no feelings. I didn't faint, I didn't vomit while I was collecting their remains. The only thing I did was think about what they had done wrong. Why were they so unlucky? What did they do wrong? What should I do to protect myself from something like this? I was desperate to learn a lesson from this to improve my chances of survival.

Photo: Max Savchenko.

On captivity

It was when the Russians had already seized Popasna and were trying to surround several of our brigades in Sievierodonetsk and Lysychansk. We were deployed with a mission to prevent this, to prevent our guys from being trapped in a cauldron. We held the line of defense on the flanks and held the roads leading to Bakhmut. The ratio of forces was tenfold not in our favor, both in terms of people and heavy weapons. Unfortunately, at some point, we were assigned to another brigade, and the officer of that brigade made a very unfortunate mistake – he left us without communication at a critical moment, just when the enemy launched a general assault on our positions. I had only seen such things before in films about World War II. I realized that what came before was not bombardment. None of that counts anymore, because such a solid wall of artillery explosions is crawling towards you. One wave rolls through the trenches. Then comes the second, third, fourth. After that, a drone starts precisely spotting the artillery and mortar fire.

The order to retreat was given, but not everyone received it due to the lack of communication. For another half a day, the four of us defended ourselves, not knowing that we were completely alone. Until we were completely surrounded. An assault group, about 40 paratroopers, came at us from the rear. And our commander ordered us to lay down our arms because of the hopeless situation.

The paratroopers treated us normally – they did not beat us or humiliate us. It got much worse when we were handed over to the Russian special services. For six months, I went through everything: torture, beatings, attempts to force me to confess to war crimes I did not commit, and much more.

Torture is varied. First, they keep you blindfolded 24/7 and do not let you sleep. That is, they handcuff you in such a position that it is impossible to sleep. And when it comes to torture, they just beat you and use electric shocks a lot. They don't get off you until you tell them everything you know. And then they also persuade you to take on some fictitious war crime in order to go to prison for ten to twenty years.

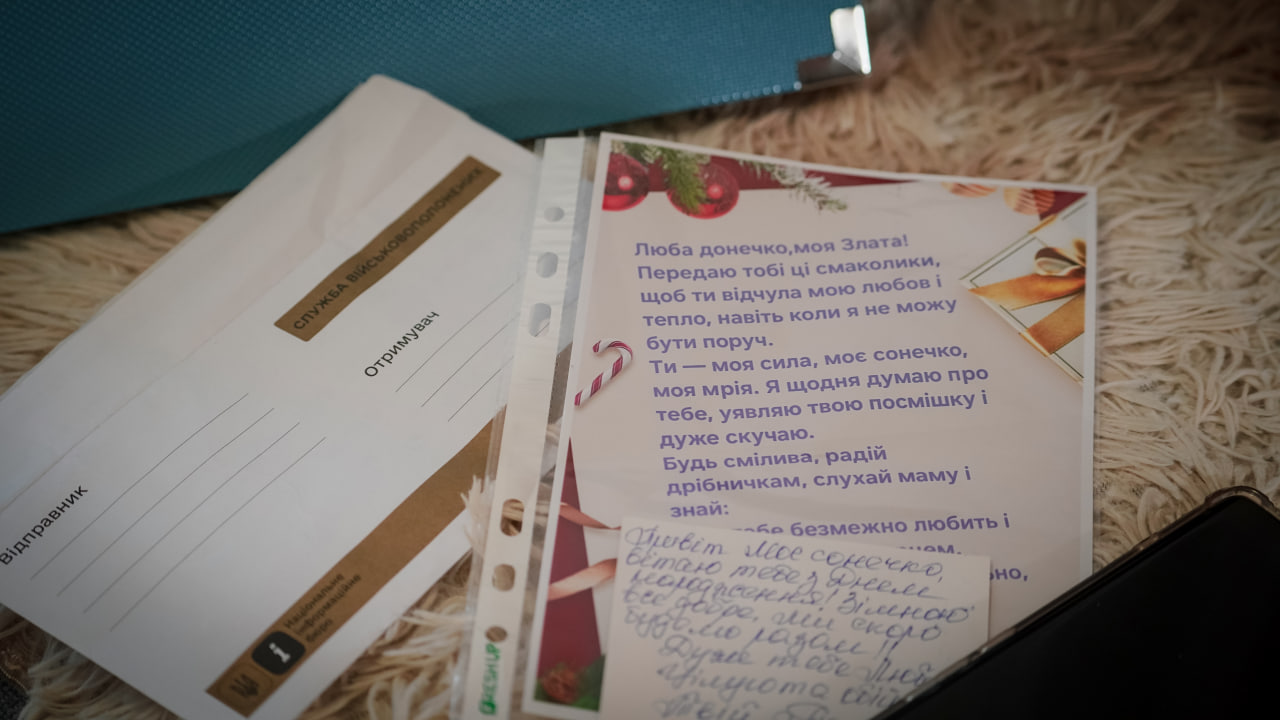

A rocket from a helicopter hit a trench. I had to pack one of my comrades into a sleeping bag

At some point, you don't feel anything anymore, not even pain. When you are electrocuted, you just look at the blue sparks in front of your eyes with interest. You become basically indifferent to what is happening to you. That is, your conscience is completely detached from what is happening to you, you don't care anymore. If they kill you, you'll finally get to sleep and rest. If they don't kill you, then there is a chance to return home. And only when they brought me to this state did they give up on me, because they realized that there was no point in torturing me any further.

In the pre-trial detention center, we were kept in a cell with unsanitary conditions. I never thought that bedbugs were such terrible creatures. They can keep a person awake around the clock. You wake up because you feel them crawling on your body underneath your clothes. No matter how much you tuck your clothes in, they still find a gap and crawl all over you.

To put pressure on us psychologically, they were constantly humiliating us, denying us some basic household needs. Once, we were not taken out to bathe for a month and a half. It was in the summer. At one point, they stopped bringing toilet paper. In other words, they did everything to make us sink, lose our humanity, and turn into weak-willed cattle that no longer have any desires or aspirations. That is, they do everything to ensure that the prisoners they return are as incapacitated as possible, crushed psychologically.

I have no total hatred for all Russians. But I have a clear understanding of my duty as a soldier – those who came to my land with weapons in their hands should stay there. I have a sense of my own righteousness in battle. It supports me a lot.

Photo: Olha Kononenko.

On overcoming PTSD

When I returned from captivity, I was in an institution where I had to show my combatant ID card at the entrance. As soon as I reached for it, the guard said: "No need, I can tell by your eyes that you fought." I was surprised, thinking: what did he see in my eyes? Later on, I noticed the difference between an experienced soldier and an inexperienced one. The one who has fought has the fear of death in his eyes forever.

One of the shocking realizations of war is that you can die at any moment. Your brain refuses to believe it. You think: I was born, spent such an interesting childhood, which I can remember so much about, studied somewhere, worked, achieved something, loved someone, someone loved me, I had dreams, plans, goals – can all this be cut short right now by some stupid piece of metal? How is this possible? It is very difficult to accept the idea of your mortality.

If they kill me, I will finally get to sleep and rest. If they don't kill me, there is a chance to return home

What is called PTSD in the military is not a disorder, it is not a disease. It's just adaptation. It's like in a biology textbook: any living organism, when it gets into a certain environment, begins to adapt to it, including changing its reflexes, behavioral patterns, survival strategy, etc. In war, we want to survive, and we quickly adjust to new conditions. But the reverse process is very difficult and time-consuming. And we return with these acquired survival skills to places where they are not always appropriate.

I got into the habit of constantly looking around, and controlling everything around me. I also got into the habit of acting before thinking. Once, I got annoyed by an ordinary drunkard in the neighborhood. He was very boring, arguing about something, wanting to borrow money for cigarettes, with his alcoholic breath reaching me. Before I could think that he was annoying me, I hit him, and he was lying on the ground. I don't remember the moment when it happened. I did not make this decision. That's when I realized that something was wrong with me. I went to the combat stress control group in my unit of my own accord.

People who are more radical in the rear than the military on the front are annoying. They decide who should be a patriot and how, they speak on our behalf. Sometimes I'm annoyed by the large number of young men on the streets. Because then I ask myself how it happened that some people feel their responsibility for Ukraine, while others don't really feel it that much and are in no hurry to do anything. For some reason, drunk people started to annoy me terribly. To the point of wanting to use force against them.

Photo: Max Savchenko.

I believe that psychological rehabilitation is necessary for everyone who returns from the combat zone. The good news is that the military themselves are beginning to realize this. It is no longer considered a sign of weakness. PTSD is not a sign of weakness, but a sign of strength, because it is acquired where others are afraid to go. The military needs help to turn a mental trauma into an experience that can be treated calmly, without emotion. I would like to thank the Ukrainian doctors who have been taking care of me for a year in a row for making our conversation possible. It is mega difficult to cope with this on my own.

I couldn't sleep after I came back, but then I learned and wasn't very happy about it. Because I began to relive all this in my dreams. Battles, captivity. Helicopters have always been one of the constant participants in my nightmares. When they were shooting at us with artillery, it was scary, but I realized that if you are not too lazy to properly equip your position, you will survive. For a helicopter pilot, it's like shooting fish in a barrel. He shoots very accurately. And if you don't have any anti-aircraft weapons, you can't do anything to counteract this. While these f*cking choppers are circling overhead, the most depressing thing is the feeling that you can't do anything.

After my treatment, before returning to service, I was undergoing a medical examination, and at that time, the wounded were being delivered to the Central Military Hospital by helicopters from near Bakhmut. When I heard the whistling of the propellers, I simply hid under the nearest tree and didn't come out of there for two hours. I understood that they were ours, but I couldn't overcome myself and come out from under cover. I suspect that this fear will stay with me forever.

I am currently writing a book about my experience. First of all, this way, my nightmares turn into a text, and I feel much calmer that I have thrown off something so black, traumatic, painful, and got rid of it. And secondly, I consider it my duty to my fellows. I would really like to leave a testimony as a participant in these events, to talk not only about myself but also about those who were near me. Because I am very afraid that after this war, we will again fall into a period of creating myths about our glorious history, while real people, real facts, and real stories will begin to be replaced by propaganda myths. In order not to let this happen, I want to leave my memories as an immediate participant in all these battles.