The scene of the action. A big report from Kherson

In the Ukrainian city of Kherson, a constant target of Russian shelling from all types of weaponry, an estimated 60,000 residents remain. Yevhenii Safonov and Yulia Kochetova ventured into the city to learn who these people are and why they choose to stay.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The decision on whether photographer Yulia Kochetova and I can enter Kherson is made by a soldier at the checkpoint. After carefully examining our passports, press cards, and permits, he frowns, puts his phone under his helmet, and walks away from our car. His stern face is familiar to me. I have crossed this checkpoint three times since the beginning of the full-scale war. The first time was in November 2022, a day after the liberation of Kherson. In January 2023, I was organizing a photo exhibition "Unbreakable Together" at the Kherson railway station. Six months later, I returned to document the aftermath of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant explosion. As a person whose passport shows Kherson as my place of birth, it has always been easier for me to get to this long-suffering city than for most of my colleagues.

Today, Kherson is not just a frontline city. It literally defines the frontline with its embankments, beaches, ports, and berths. A typical daily report from the city reads: "The enemy made 82 attacks, firing 342 shells. There were hits to critical infrastructure, an administrative building, and a store. One person was killed, and another was wounded." It is dangerous to live in Kherson. However, about 60,000 people live here now, a fifth of the pre-war population. Why do they stay? What do the residents of the city, where the curfew starts at eight in the evening, do for a living and how do they spend their leisure time? For whom does the Kherson maternity hospital work? Yulia and I want to find out and are waiting for the soldier at the checkpoint to let us into Kherson. After making sure that there is nothing forbidden in the car, he gives us back the papers, tells us to take care of ourselves, and taps on the roof.

Chornobayivka. A hero village

A few kilometers before we reach Kherson, we stop at an airplane monument that towers over two signs: "Airport" and "Chornobayivka". While we are putting on our body armor and helmets, a car stops behind us. Three guys jump out of it and head towards the Chornobayivka sign. Against its background, they take turns taking photos, posing with their biceps tense. We are all standing on the edge of the airfield, a historical site where the epic wipeout of Vladimir Putin's troops took place.

In February 2022, having already occupied Kherson, the Russians were eager to move further west as soon as possible. It was no longer possible to transfer forces from Crimea to the right (west) bank of the Dnipro by land, as Ukrainian Smerch multiple rocket launchers from Mykolaiv were pounding the Antonivskyi Bridge and Nova Kakhovka crossing. The enemy desperately needed Kherson Airport for air transportation. Here, at the airport near Chornobayivka, the Russians set up command posts, ammunition depots, helicopters, and ground equipment. Over the course of eight months, the Ukrainian Armed Forces attacked the occupiers' base more than 20 times. Goliath had fallen. Unable to gain a foothold in Chornobayivka, the occupiers were forced to flee the right bank of Kherson Oblast.

Yulia and I stop by the celebrated village. Everything here is still familiar to me – in the ‘90s, my parents, both service members, served in a helicopter regiment based nearby. I went to the third grade in this village. Now we are going to visit Halyna Syniuk, a school teacher with whom I have kept in touch.

Halyna Hryhorivna welcomes us with open arms into her spacious and well-kept house. Her husband, Mykola, is there, as well as – surprisingly – a crowd of children. It turns out that after the missile hit the village school, the entire fourth grade has been attending classes at Halyna Hryhorivna's house. She has set aside the largest room for the classroom: there are desks in three rows, a marker board, a screen with a projector, and a brick stove covered with children's drawings.

The photographer and I find ourselves in a ring of schoolchildren, who are springing with curiosity. The tallest boy steps forward: "May I hug you?" The girl with a braid says: "Me too!" In a moment, we are immobilized by the hugs of the entire 4B class.

After sending the children to their desks, Halyna Syniuk takes us to the kitchen, where her husband is already making tea. I describe the scene I saw at the signpost and ask her what it's like to live in the legendary village.

"Oh, at the passport office in Ternopil, where we fled the occupation, people from other departments came running to see a person 'from that very Chornobayivka’," Mykola laughs.

"I decided not to cut my hair until Chornobayivka was liberated," Halyna recalls. "But at some point I realized that I couldn't teach online lessons looking so disheveled, so I went to a hairdresser. When the hairdresser found out where I was from, she asked: ‘Are you proud?’ I explained that maybe I will be someday, but for now, it hurts so much that you don't feel anything but this pain.”

When Chornobayivka was liberated, Halyna and Mykola left their two teenage sons in Ternopil, where they had already started their studies and returned. The children refused, but Halyna said that if she did not return, she would die.

Today, she estimates that a quarter of the pre-war population lives in Chornobayivka. Some left during the occupation, others after. However, many, like Halyna, returned, unable to bear living away from home: in someone else's house, without work. I ask what kind of work is available in Chornobayivka.

“An ATB [supermarket] was recently opened," Halyna says and, after a moment's thought, adds, "People also do gardening... Generally speaking, there is some work.”

In addition to teaching school in her own home, she regularly gives online Ukrainian language lessons to children from Chornobayivka who now live in other regions of Ukraine or abroad.

"Overall, it's very dangerous," says the teacher, nodding toward the classroom, where the children's noise is already growing. "There are constant hits nearby. Recently, a house was hit nearby: a man entered the bathroom and never returned.”

Every morning, Halyna and her children pray to get through the day safely. On November 23, 2023, when Chornobayivka was under heavy shelling from morning to evening, the teacher took the class out into the corridor, where they stood hugging each other, reading prayers and singing psalms all day.

When Yulia and I finish our tea, Halyna Syniuk takes us to the board.

"Glory to Ukraine!" the teacher exclaims. "Glory to the heroes!" the class responds in chorus. "Glory to the nation!" Halyna Hryhorivna continues. "Glory to the 4B [class]!" the children shout.

I ask who wants to become what. It turns out that Ivanko and Myshko want to become police officers. Yulia asks if they want to issue tickets for parking violations. The class loves this joke. Everyone is laughing.

Yasmina dreams of becoming a fashion model. When Chornobayivka was occupied, she and her family went to Italy, missed her friends there, and now she is glad to be back as she feels better in Chornobayivka. Daria wants to become a designer, she likes to decorate her room. Nastia sees herself as a professional handball player as she attended this class before the war, but now the gym is closed. Maria is thinking of becoming either a dentist or a veterinarian, so that she can treat cats, including two of her own.

"My dog was killed by a shrapnel," says Myshko, a future policeman. "Barsyk was white as snow.”

“And my friend's grandfather went to the market in Kherson, came under fire, and died," says Platon.

"And when my parents and I were sitting in the basement, a missile hit our yard and smashed all the windows," says Ivanko.

The children talk about death in low voices. They feel the tragedy, but they do not realize how far from normal the life they live in Chornobayivka is. The fourth graders are quite optimistic. The motto they proclaim in chorus: "Every day brings us closer to victory." All of them see their future in their hometown. Except for Yasmina, who doubts that she will be able to make a career as a fashion model in Chornobayivka.

While Yulia is arranging a "professional photo shoot" for Yasmina, I listen to the boys speaking and note down how much they have raised for drones for the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Ivanko praises Myshko for giving all his pocket money to the fundraiser. In return, Myshko praises Ivanko for donating the money he received for his birthday.

I notice that the children of Chornobayivka are unusually considerate and polite to one another. We were definitely different—prickly and pugnacious. Perhaps this is because we did not have to pray under fire, holding onto each other.

Having successfully derailed the daily schedule of the 4B class, the photographer and I are getting ready to leave. Of course, we hug the children goodbye.

Source of the resource

The war has discolored Kherson: shop windows are boarded up, and advertising signs are fading, becoming pale and illegible. Only concrete shelters near bus stops break out of the general drabness, as they are decorated with colorful murals, probably so that the structures do not deepen the sadness with their original appearance.

The facades of the buildings are pierced by shrapnel. There are still some windows intact, but they are mostly boarded up with plywood. There are also swaths of dead leaves on both sides of the road.

There are so few cars on the road that at one point Yulia asks me who I turn on my turn signals for. The fact that there is still life in the city is only evidenced by the working Silpo supermarket, a gas station, and a Nova Poshta mail service branch. X-ON radio, the first and so far the only local station, has also recently started broadcasting in Kherson.

“Of course, other stations broadcast to Kherson, but they are all repeaters. Unlike them, we are based here. Sometimes we even say on the air: ‘People, be careful, the shelling continues’. Because we can hear it ourselves," says Kateryna Tsymbaliuk, founder of Radio X-ON, leading us into a small studio curtained off with noise-proof curtains.

Kateryna is in charge of music, which currently makes up 70% of the airtime. Right now, X-ON is playing something from Zhadan i Sobaky. They play "everything that is not downright pop": Rammstein and Prodigy are mixed with Khrystyna Soloviy and Braty Hadiukiny.

“Sometimes, of course, I get roasted by our producer Denys Serhiyovych, saying that this is not our format (inappropriate choice of music - ed.), such formats do not exist at all! And I say, 'Who cares, it does exist here!’" Kateryna smiles.

Her co-host, journalist Tina Fedorchuk, prepares the news block. In addition to the news, interviews with representatives of local authorities, the military, volunteers, and opinion leaders, to which Tina refers primarily to writers and historians, will soon appear.

"Oh yes," Tina assures me when I raise an eyebrow, "it's a great time for local historians! After all, people are seriously interested in the history of Kherson Oblast.”

"There used to be one narrative: the city was founded by Catherine the Great, and we should bow to her forever,” Kateryna joins in. "But there were also Kamyanska Sich and Oleshkivska Sich here before. Before that, there were Greek settlements. So we are bringing all this knowledge to the surface.”

During the occupation, Tina Fedorchuk filmed reports from Kherson for Channel 5. For a long time, she went on air without covering her face. In September, she realized that she could not stay in the city any longer. The Russian military, Tina recalls, were everywhere and resembled cockroaches in a dirty kitchen – it was disgusting seeing them.

The journey to the government-controlled territory took one month. It took her and her husband two days to get to the checkpoint in the village of Vasylivka, Zaporizhzhia Oblast. They stood in line for two weeks, but could not leave as the Russians sent them to Tokmak for filtration. It took another two weeks to get a pass and return to Vasylivka through a series of checkpoints. It was forbidden to spend the night on the roadside, so they had to look for accommodation in the surrounding villages. Tina recalls that many refugees did not endure the ordeal: some returned in despair, others because they ran out of money. Some elderly people died in cars in the scorching sun.

Kateryna Tsymbaliuk stayed in Kherson throughout the entire period of occupation. She attended anti-Russian rallies until the end, fully aware of the risks. Now, laughing, she recalls how she used to wear elegant underwear so that her body would look decent during identification. The Russians behaved confidently in the city, demonstrating that they were really here for good.

"That's why November 11 came as a surprise to us," Kateryna recalls. "Shortly before that, I saw an endless line of fire trucks and ambulances moving down Perekopska Street toward Antonivskyi Bridge. I didn't realize then that they were taking out the municipal transport [as they were leaving].”

Soon after the liberation of Kherson, Kateryna realized that an information vacuum had formed in the city, and if it was not filled with reliable information, there would be enemy psyops. That's how Tsymbaliuk, who has experience working in radio and TV, came up with the idea of a radio station. A team and sponsors appeared. First, they launched online radio, then got an FM wave.

The hosts say that X-ON's main task is to give people positive messages, which is the resource without which they cannot win. Kateryna and Tina have mastered the ability to find the positive in the reality around them. The cinemas are closed, but they work in Mykolaiv, 70 kilometers from Kherson. There are no bars or restaurants, but there are board games and read-alouds.

“My husband recently said: ‘Do you remember the TV series we used to watch?’ I responded: ‘What TV show, I read you the book!’" Kateryna laughs.

Why do they stay in Kherson? Kateryna considers this question intimate and generally not something that should be asked of Kherson residents. Everyone has a good reason. Some cannot leave because of their elderly parents. Some people think it's necessary to stay because as long as there are people here, the city lives and holds on. Some people can't imagine life outside their homes. Kateryna knows for sure that she will be happier here, even under fire, than anywhere else.

Socks with a surprise

Almost all cafes have closed in Kherson, but there are coffee shops. The 11/11 smells like confectionery and freshly ground coffee beans. The only customers, two women, are talking animatedly about something. On the table in front of them is a cappuccino and an unpacked box of chocolates. Maryna and Hanna agree to answer our questions. I ask about work in Kherson.

“I live in a private house, there is plenty of it. ‘Roses, berries…’" Maryna answers and pushes a box of chocolates towards me.

"Do you raise roses?" I know of at least one working florist in Kherson and decide that I have found a supplier.

“Why do you say ‘raise’ right away? They grow by themselves," Maryna smiles slyly.

"The roses were growing, are growing, and will continue to grow," Hanna interjects with the tone of a teacher explaining a fundamental law of nature. "We are living as we always have lived!”

Maryna recalls how a platoon of Russian soldiers came to her neighbor's house during the occupation. When they saw the cozy yard, they were puzzled: "Why?" The neighbor tried to explain that it was just for esthetic purposes. Before they could digest the answer, the Russians noticed a beagle and a shih tzu in the yard and inquired: "What's that for?"

"That's what I'm saying about roses: they are just for esthetic purposes," Maryna laughs and, after a pause, removes the smile from her face. "But seriously, we all work – we help our guys on the other side (the military holding the bridgehead on the left (east) bank - author's note). We are preparing canned food, making stew, collecting clothes.”

“The whole city – no matter who you ask – is supporting the guys. Whole neighborhoods are organizing and working," Hanna joins in. "Boats, cars, drones – these are all consumables. Right now, we're collecting money for these... waist-high boots... waders!”

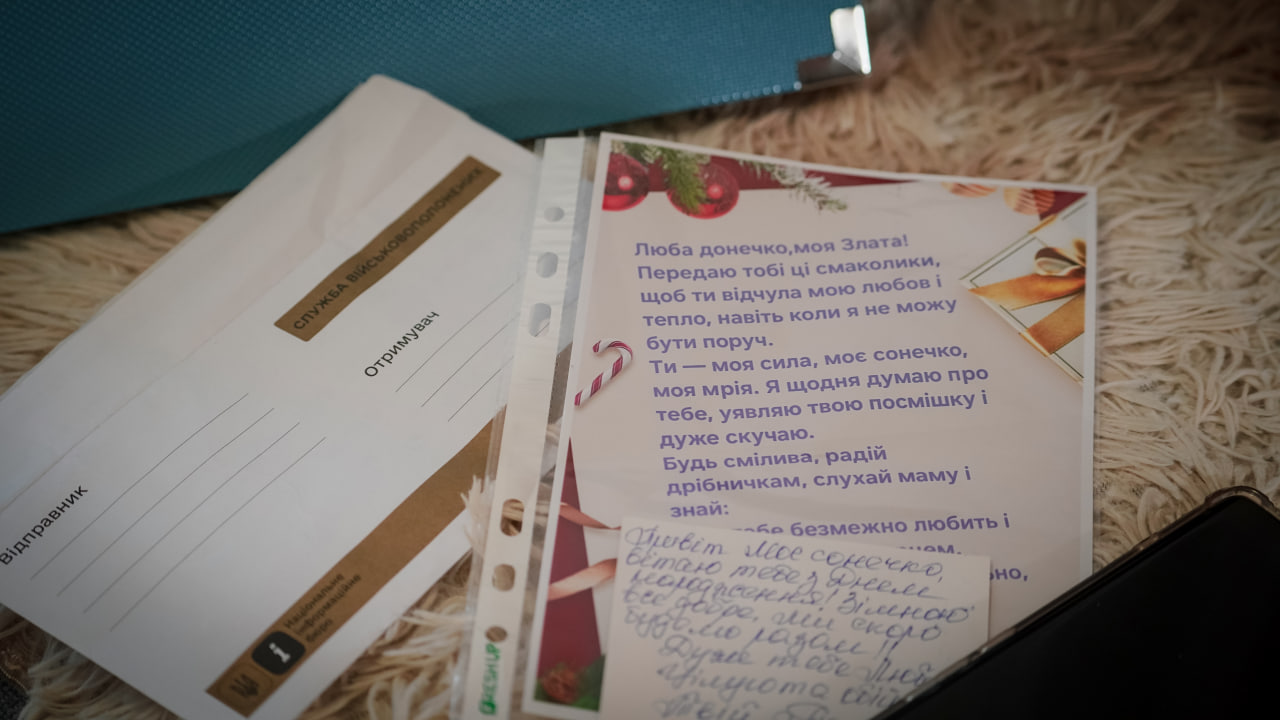

Women avoid talking about their own earnings. It seems to be an indecent topic when there is a really urgent one – the needs of the defenders. As for Hanna, she is responsible for the supply of socks. Right now, she has 60 pairs ready to be shipped. There are some that the photographer and I need to see, so Hanna takes us to her place. She lives in a high-rise building nearby and is the head of the local condominium. A small room on the ground floor is used as her workplace, and now as a sock warehouse.

Hanna coordinates the knitters who ensure regular deliveries to the front. Skillfully digging into the boxes, she pulls out piles of socks.

"Girls sent these to them, I think, from France. And these are knitted by an old lady from our building, who is almost 80 and can hardly walk. And these are socks-boots, they stand upright!”

Anna confidently puts them on the table. These socks really do stand.

There are also socks with prayers and socks with knowledge of English, which are knitted by a teacher from school #27. Finally, Hanna finds the ones she called us for: each pair is fastened with a miniature bow. She offers to put my hand inside the product. I obey and feel a candy in each sock. Hanna assures me that even the toughest soldiers' jaws tremble from such cuteness.

As the head of a condominium association, Hanna knows the statistics: before the war, 384 apartments were occupied in her building, and now there are 282. That is, only a quarter of the residents have left. This is atypical for the city. According to official figures, Kherson is now home to 67,000 people (300,000 before the war). Many leave, but many return. In addition, the number of newborn Kherson residents is growing.

Push on, Kherson

Kherson Perinatal Center No. 1 is a five-story building that has been pierced in several places by Russian munitions. This is the first time I've been here since I was born. The head of the center, Svitlana Kulinich, a calm, smiling woman in a sweatshirt pulled over her shoulders, meets us in her office.

I tell Svitlana that we would like to document the emergence of new life in Kherson. We need a photograph of an obstetrician triumphantly lifting a newborn baby, still attached to its mother by the umbilical cord, blind and wrinkled, emitting its first cry, preferably against the backdrop of a window that shows something recognizable: the Monument to the First Shipwrights or at least the Kulish Drama Theater.

Svitlana Kulinich, looking at us carefully over the top of her glasses, warns us that she will not be able to organize a view from the window: due to the shelling, she now delivers babies in the basement. As for the rest, she has to make a phone call.

"Artem Yuriyovych, when are we delivering the twins?" Svitlana asks over the phone and, having received the answer, nods promisingly.

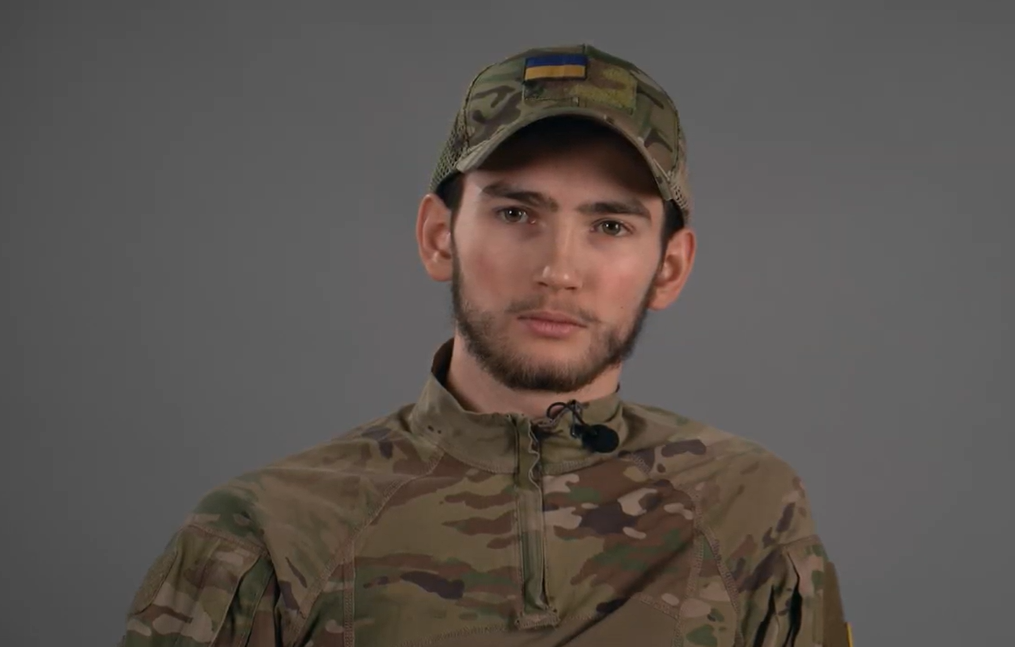

During a tour of the ruined floors of the maternity hospital, we meet Artem Ostapchuk, a young obstetrician whose life experience has been generously enriched by dramatic stories over the past two years.

Artem lives in Muzykivka, a village located just north of Chornobayivka. When the Russians occupied Kherson, they immediately blocked the road connecting Muzykivka to the city. Electricity was cut off, and ambulances were not allowed to run. The village remained in such isolation for a month. On March 3, at five in the morning, Artem, along with another obstetrician and an ambulance attendant, were preparing to deliver a baby in the village. The only instrument they had was a needle holder that had been lying in the closet since their student days. The only medicines he had were pills for uterine contractions.

"If something had gone wrong, I would have been unable to do anything," Artem recalls in horror.

The birth was delivered by candlelight, with candles taken from a local monastery. The room was heated by a generator, with a meager supply of gasoline. A healthy boy was born. Artem has no contact with the woman who gave birth, but he read in the village newspaper that the mother and son are now in Poland and are doing well.

Artem Ostapchuk calls the liberation of Kherson the happiest moment in his life. The tension in which they lived under occupation is indescribable. But since then, the drama in their lives has not diminished. Missiles flew into the maternity hospital twice, each time on his shift. There were no casualties, but a lot of equipment was burned in the fire.

Kochetova decides to take a picture of the obstetrician against the backdrop of the destruction. He agrees, but admits that he was recently photographed for the foreign press, and, in his opinion, a better shot could not be made – a ray of light fell on him through a hole in the wall, and it turned out to be a masterpiece. Yulia snorts in displeasure.

Svitlana Kulinich takes us to the roof. From here, we can see the Mykola Kulish Music and Drama Theater and the adjacent square. There is an empty pedestal in the middle of the square as the statue of Kherson's founder, Grigory Potemkin, was taken away by the Russians. Along with the monument, they also took Potemkin himself – the prince's skull and bones, which had been kept in a crypt in St. Catherine's Cathedral (Moscow Patriarchate church) for 230 years.

To the left, behind the church domes, one can see the port cranes. Behind them is the Dnipro River and the left (east) bank. Somewhere there, the enemy is entrenched. As if looking for their positions, Svitlana silently stares into the distance. Her team’s situation is difficult. Before the war, they delivered an average of 10 babies a day, now they deliver 10 a month. If there are even fewer women in labor in the future, the hospital may be closed.

For now, the obstetricians have work. The twins that Artem Ostapchuk will soon have to deliver are being borne by 39-year-old Zarema. When she received the news that her children's father, a soldier, had gone missing at the front, pregnant Zarema almost decided to have an abortion. But after talking to doctors, she agreed to give birth.

Zarema's babies are due any day now. Until the birth takes place, the photographer and I drive along the deserted central streets and stop at the Yuvileynyi Cinema and Concert Hall. The building and the square in front of it bear the marks of missile attacks. Three people are crossing the empty square: a guy carrying packages of food, a girl leading a beagle on a leash, and an older woman with a black Labrador. Suddenly, explosions are heard: it is not clear whether something is being fired or there was a hit. Neither people nor dogs react in any way.

A photographer I know told me that he met children in Kherson who were riding scooters around the center of the city wearing bulletproof vests. Yulia and I don't meet any children in the center, but we do come across a group of men playing volleyball. One of them, a broad-shouldered man with gray stubble, is watching the game.

"I am a pensioner. I have adult children, they moved to Kyiv," he says, not taking his eyes off the sports court. "I visited them recently, and I couldn't sleep at night. I can't fall asleep in silence, I keep waiting for the noise to start. The kids say it won't, so go back to sleep. But I just can't. I'm used to this: there are bangs here every night, and I fall asleep like a baby.”

The city falls asleep

We spend the night at Nika Khaborska's place. I met her in Kherson on June 6, 2023, the day the Russians blew up the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant. Back then, Nika and a team of volunteers were evacuating people from flooded houses on Kulisha Street. Before that, she lived in London, where she worked as an art dealer. Last summer, she came to her hometown to visit the cats. When the flood occurred, she joined a team of rescuers, met her love among them, and decided not to return to London. Later, she discovered that there were many families with children living in Kherson, and now she organizes parties and art therapy sessions for the kids in the bomb shelters. Nika's boyfriend recently volunteered for the frontline. In between volunteer work, she organizes fundraisers for his unit.

Nika confirms the words of teacher Halyna Syniuk from Chornobayivka: many families left Kherson but returned because they could not stand the difficulties of life in displacement. It's not just the miserable amount of monthly allowance for "internally displaced persons" (UAH 2,000 ($50) for an adult, UAH 3,000 ($74) for children and people with disabilities), but also the attitude of some residents of the regions far from the front towards IDPs.

"IDPs expect sympathy and help, but they don't get it," says Nika. "Many people here don't understand what it's like to live in a frontline city, and what it's like to start life from scratch.”

I get a room on the second floor, with windows spanning the entire wall, looking directly south. I fall asleep peacefully without any noise. But around four in the morning, I am woken up by dull explosions coming from somewhere far away. Every day, the enemy fires about 50 (and sometimes more than 200 shots) from Grad rocket launchers, mortars, cannons, tanks, and anti-aircraft guns at Kherson Oblast. Usually, a third of them fall on Kherson. When I woke up, I could clearly hear the whistling sound of flying shells in the sky.

In the morning, I ask Nika if the intensity of the night's shelling was higher or lower than usual.

"There was no shelling today," she says confidently.

Looking at my round eyes, Nika admits that she no longer wakes up from sounds – only from vibrations when a plane flies very close.

Birds, insects, collaborators

Russian attacks in Kherson Oblast have damaged 14,000 residential buildings, 181 hospitals, 43 industrial facilities, 700 transformer substations, and more than 850 kilometers of gas pipeline. Bus depots were looted and smashed. And this is not a complete list of the damage, the total cost of which is difficult to calculate. The damage caused by the explosion of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant alone amounts to more than 146 billion hryvnias ($3.6 billion). At the same time, most of the agricultural land, which has always been the main source of income for the region, is still mined. A year after the liberation, only 80,000 hectares – 12% of the de-occupied territory – have been cleared.

When fleeing, the occupiers took away not only material but also cultural values. For example, the Oles Honchar Oblast Library lost rare editions of the eighteenth century, and the local history museum lost its collection of ancient weapons and Scythian gold.

"They took numismatics, lapidaria (a collection of ancient writing on stone slabs – author's note), and everything containing precious metals," says Mykhailo Pidhainyi, senior researcher at the Nature Department of the Kherson Museum of Local Lore.

Mykhailo Pidhainyi used to catalog birds, insects, stones, and bones in the museum, as he says himself. He would do it now, but he cannot conduct observations in mined areas. So for now, he helps the historical department by cataloging shell casings, shell fragments, and other war artifacts that are to become museum exhibits.

Mykhailo's wife, daughter, and grandson left Kherson. He stayed in the city with his son-in-law.

“We are sitting here together, listening to the sound of the 3D printer, which is working around the clock. We print things for the army," he smiles conspiratorially.

Mykhailo has a beard, and gray hair pulled back in a ponytail. Behind his massive glasses, he has a lively look that flashes whenever the conversation turns to a topic that really excites him.

Mykhailo is sincerely concerned about collaborationism. The scientist's inquisitive mind finds problems from psychology and sociology in it, and he finds solving them no less interesting than arranging stuffed steppe gophers on a diorama.

He recalls how shocked the Kherson collaborators were to realize that they would have to flee the city.

"Oh, it was such a tragedy, they were almost ready to kill themselves!" he rolls his eyes (seemingly with pleasure).

There is no city where the Ukrainian army is adored as much as in Kherson. There is no city where traitors are so hated.

During the occupation, the collaborators settled old scores, snitched, and nagged the authorities. There were people ready to collaborate with the occupiers everywhere: school teachers, police officers, entrepreneurs, officials, doctors, and journalists. Why?

Nationality and language were definitely not key, Mykhailo believes. According to his observations, wherever sympathy for the occupiers was sincere, it grew out of nostalgia for Soviet life. However, more often, collaborators were driven by mercenary motives rather than ideological ones. For example, those who felt oppressed at work would suddenly see career opportunities and strive to become leaders.

However, Mykhailo cannot explain some metamorphoses. For example, the case of Kyrylo Stremousov, an eccentric blogger who served as deputy head of the occupation administration and died in a car accident under unclear circumstances a few days before the liberation of Kherson.

“I was well acquainted with them, such a bright young man. With a lively look, a truth seeker! He tried to repeat the journey of Che Guevara, but he rode a motorcycle not from Argentina to Mexico, but from North America to South America. I read such perceptive poems about Ukraine. Suddenly he started to write wild nonsense. How did he come to this?” the scientist wonders.

He has only one explanation: Stremousov, having become the father of six children, found himself in a difficult financial situation, fell into debt, and started engaging in shady business, eventually getting deeply involved in it.

Mykhailo Pidhainyi has a complicated hypothesis on any issue, but recently he was given a case for a howitzer powder charge to describe, and now the scientist is tormented by the question: why the hell is it so heavy?

"The M777 howitzer has a lightweight plastic case," he explains. "But the M119 has a huge steel tube. I don't understand, what for?”

Everyone's own choice

When we arrive at the address where we are supposed to talk to the administration representative, we find out that the meeting is postponed as the shelling has started, and the administration employees are taking cover. Explosions are heard, and we also seek shelter. The closest one is a ring-shaped gabion (a mesh structure filled with stones - author's note). Inside is a sports ground. An elderly woman wearing a knitted hat is catching her breath near one of the exercise machines. Yevdokiya Serhiyivna quietly explains that her doctor ordered her to do the exercises after a stroke. I ask Yevdokiya how old she is.

"Eighty-two," she replies. "I had a stroke today. Do you want to celebrate? I have a cake at home.”

She has a one-room apartment on the fourth floor. There is a sheet of plywood in the balcony window where the broken glass used to be. There is a pile of pills on a stool by the bed. On the coffee table, there is a bowl of salad, sandwiches, and a cake that Yevdokiya baked herself.

Yevdokiya Oleksiyenko was born and raised in Poltava Oblast, in the village of Stara Kozacha Stanytsia, which stood on the banks of the Sula River. There were seven children in the family. Her older brother was killed in the battles near Warsaw when he was 18. Her father returned from the front without a leg and died early. Yevdokiya's childhood was spent in the postwar period. It was hard, but she also has good memories. The village was beautiful, and the water in the river was the clearest and cleanest in the world. When the Kremenchuk Hydroelectric Power Plant was built, they got electricity. The school class was friendly, and one world-renowned scientist and one general graduated from it.

“The scientist now lives in America. He studies the brain. And the general lives in Moscow and is fighting against us.”

“How do you know this?”

“We all keep in touch. Well, those who have computers. My classmate wrote to this general. And he said that we have been brainwashed, and Putin is doing everything right. What else can I say?”

When Yevdokiya was 18, a friend suggested that she move to Kherson. It was warm there, a cotton mill had just started working, and there was work available. Yevdokiya accepted the offer. She graduated from the Kherson Institute of Technology, got married, and gave birth to a son. Now, she says, Kherson is more of a home to her than Poltava Oblast. Before retirement, Yevdokiya worked as a personnel officer at a trolleybus depot for 20 years, so many people in the city know her.

Her husband passed away in 2017. Her son would be celebrating her birthday with her right now, but he lives in the Ostriv district (a neighborhood in Kherson that is under the most intense shelling - author's note), and recently his yard was hit, so her son is busy fixing windows.

Along the front line, there are many towns and villages whose inhabitants live under constant shelling, but refuse to leave their homes. For some people in the rear, they are either “awaiters [of ‘Russian world’]” or insane. Psychologists have a different explanation: in a difficult situation, we tend to choose the solution that requires the least amount of action. We leave life as it is, shifting responsibility for our own fate to external circumstances.

Obviously, there is evidence for all these assumptions in life. But I didn't find it on my trip to Kherson. I didn't meet people who would complain about their troubled lives and let things slide. On the contrary: instead of inactivity, these people chose action. And now they entertain children in bomb shelters, lead knitting groups, spread positive messages on the radio, deliver babies, and prepare a collection of exhibits for the future war museum. Russia is making every effort to make Ukraine's frontline cities uninhabitable and deserted. In response, Kherson residents extend their middle finger: the roses have grown, are growing, and will continue to grow.

Everyone we spoke to has a sober assessment of the risks and makes a conscious choice.

Everyone except Yevdokiya Serhiyivna. She simply has no choice as she is no longer able to start life from scratch. She says that she is not discouraged, that "everything will get better, and we will live our best lives." She is only afraid of rockets. When the shelling starts and her home shakes from explosions, Yevdokiya Serhiyivna lies down on the bed and curls up into a ball so tightly that it seems she herself is about to fire.

We clink cups of cherry compote, and I ask the birthday girl what she would like me to wish her. She doesn't hesitate: "Peace." She persuades me to take some apples for the road. Photographer Yulia tries to refuse. I know it's futile, so I take them.

P. S.

A day later, Zarema will give birth to two healthy sons. Their childhood will continue during the war and will most likely be difficult. But there will definitely be good moments too.