"I realized that if I didn't take them out now, there would be no other chance."

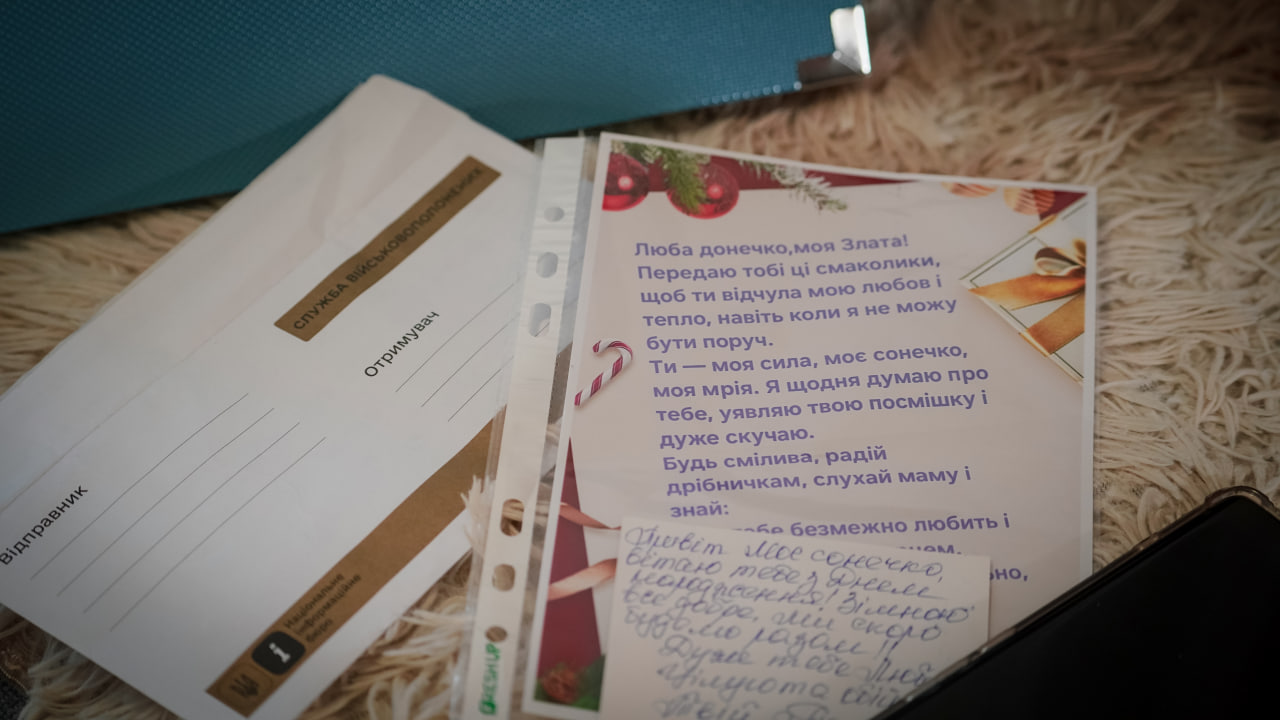

There was a real risk that the film by Mstyslav Chernov, Evgeniy Maloletka, and Vasylisa Stepanenko, 20 Days in Mariupol, would not be released. After the team managed to transmit photos of the aftermath of a Russian air strike on a Mariupol maternity hospital from the siege, the occupation administration began hunting for the journalists. Saving them, as well as the footage they had shot, became a personal matter for police officer Volodymyr Nikulin. He believed that if the world learned the truth about the cruelty of the Russians, it would stop the war.

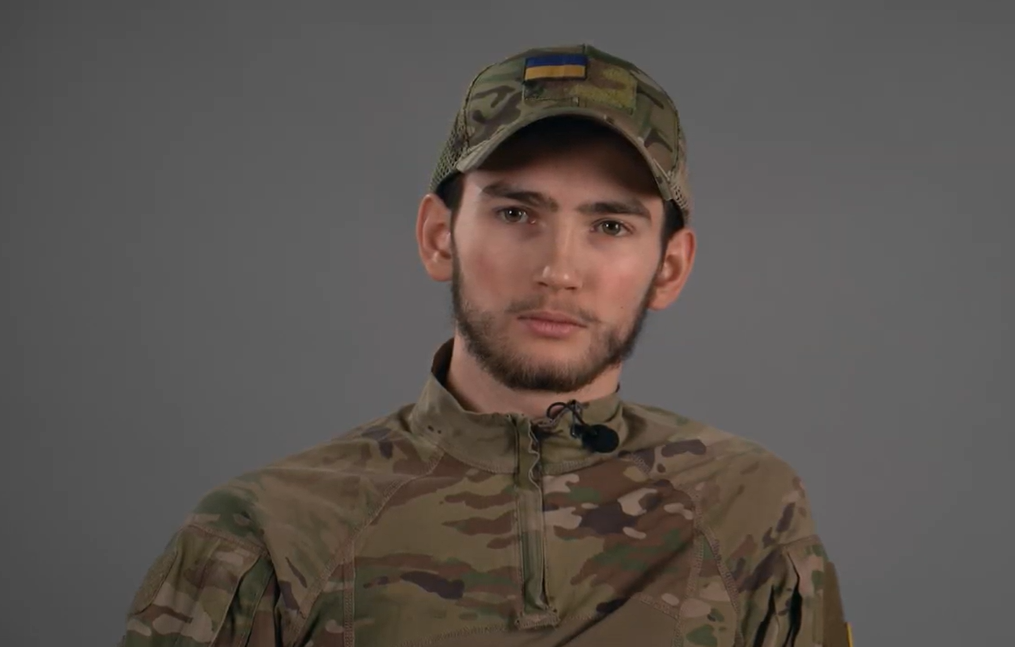

Volodymyr Nikulin has been working in the police since 1992. In 2014, he left the temporarily occupied Donetsk, and in 2022 he was stationed in the besieged Mariupol. In August 2023, he was wounded in the back by a missile fragment while helping injured civilians in Pokrovsk. He currently holds the position of Deputy Head of the Documentation Department of the Main Directorate of the National Police in Donetsk Oblast.

About the invasion

February 24 was the day immediately after the Russian invasion. We have a procedure called "combat alert". I received a call from my superior. I asked him: "Is this a combat alert?". And this was the phrase: "Yes, a combat one". I don't remember if I heard sirens, I don't remember if I heard shots. I only remember these words: "Yes, a combat one". I realized that this meant war.

[On the first day of the invasion], we had to organize the evacuation of documents. It concerns personnel issues and the activities of the police department. All police officers need this documentation, not just the police in the region. It also included documents related to the war: what we did, how we did it, and who participated in the Anti-Terrorist Operation, and later in the Joint Forces Operation. We divided the documents into categories with a restricted access stamp. Everyone had a package with special markings. We took everything to a safer area.

The fact that the situation was difficult was clear from the very first day. Those who stayed behind did not realize the complexity of the situation. We all thought that Mariupol would remain Ukrainian. Those who did not think so should not have stayed.

Tension was in the air. The worst thing that happened in the city before the first bombing was the silence. The silence was terrible. Later, when the city was destroyed, when the city burned down, I realized what silence was.

Every hour, every day, we realized that the Russians could seize the [police] building. We had to fortify it. I did it with the guys who stayed behind. A few locals also came to help. The first day: defense of the building, interaction with other units, with Azov, with border guards. No one taught us [how to act in a war of such intensity], we had to help deliver food and distribute it in shelters.

We thought that Mariupol would remain Ukrainian. Those who did not think so should not have stayed

When people saw me in a police uniform, they hoped that I would tell them something [reassuring], but I couldn't tell them anything. Maybe I should have lied a little and said that everything would be fine.

.jpg)

Civilians asked me when the Russians would open the corridor, when they would let us out. I don't know why I said that: "People, I'm sorry, I can't promise you anything. Can you negotiate with the mad dogs on the street? We can't come to an agreement."

Those were my words. I regret it now. Maybe I should have worded it softer.

About police work

Before the invasion began, the front line seemed to be 25 kilometers from the eastern side of Mariupol. 25 kilometers can be covered in one or two days. But the siege was laid only in early March, and the siege was completed around March 6. As I remember, on March 11, the Russians started an operation in the city, coming in from the villages of Nikolske and Manhush.

Since March 3, there was no robust communication. We received an order to stay in the city. We decided how to act on our own. There were no instructions on how to act when the city is being destroyed. How to act if there is no water supply, if shops and pharmacies are closed? I don't know if there is a country that has a protocol on how to act during a terrible war.

After we lost communication, it was very difficult to coordinate with the military administration. It was important to react [to events]. How did people report shellings? They approached the patrolling police officers and gave a verbal message. We spread the information further through the radio station.

I won't say much about the fact that the mayor left Mariupol. During hostilities of this magnitude, the city authorities do their job, but they did not have many opportunities. How can they provide [citizens] with food and shelters if it is the responsibility of the law enforcement agencies? In such circumstances, local authorities do not play a big role. I don't want to give an assessment of [the mayor's] actions because everyone decided for themselves. I know that the top officials stayed put. I am glad we did not leave the city and did our part. As for those who left, they should be judged by people.

-min.jpg)

About hope in the besieged city

The hardest part was realizing that not all people understood what a full-scale invasion was. They did not behave very humanely. This is the downside of war. I cannot say that all Mariupol residents stood up for each other. Many people drowned their grief and reality by looting shops. The police, the Armed Forces, Azov, the National Guard, and other units needed help. But there was not much of it.

We were in the city to prevent the situation from getting out of hand. Drug addicts who went cold turkey got very aggressive. Marauders could do anything at night. Whenever we showed up, this scum didn't bat an eye. [And sometimes] they were not even afraid of shelling; they walked the streets like zombies. I was with reporters, we were hiding during a shelling. And some drunkard was walking down the street and shouting: "Don't be ashamed! Look, all the people are walking, and no one is afraid." They did not realize what was happening.

It was impossible to [stay] in Mariupol without faith. Why stay there if you don't believe? When we were already under siege, when the fighting was already going on in the central part of the city, we rejoiced in small victories. Fighting was going on in the central part of the city and on Myru Avenue, and then reports came that our forces had taken back three stops. What is the [significance of] three stops? But we were so happy. Then came the news that [the Russians] had completed a landing operation. And then reports that they were all killed. How can we assess this now? It's ridiculous: you're under siege, but you're rejoicing. We may not live to see our guys coming from Volnovakha – it was sad. A siege is sad. But there was no despair or fear.

About the acquaintance with authors of 20 days in Mariupol

On March 9, we heard on the radio that a bomb had fallen near the children's surgery.

We saw a very large crater. We saw women coming out of the hospital. I noticed military uniforms, police, National Guard. And then there was another one – blue bulletproof vests. I was very surprised that journalists were in the city. They said they were from the Associated Press. They were Mstyslav Chernov, Evgeniy Maloletka and Vasylisa Stepanenko.

.jpeg)

On March 11, a [Russian] sabotage and reconnaissance group launched an attack on the hospital. They shot doctors and nurses. It was a special unit of the Russian Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU). When we were near the hospital, I saw a Russian tank hitting the residential buildings. It's impossible to start a fight near a hospital [when you're next to civilians]. We had to keep ourselves in check, to restrain ourselves from shooting [in response]. The Azov guys could not hold back. They were shooting at the Russians. I realized that this was wrong, and then I heard that people at the hospital were begging not to fire shots. [On the other hand], it saved many lives. An Azov soldier, call sign "Derek," was shooting right from the hospital. The Russians got so scared that they were not heard or seen for another day.

We had no communication; no one [except for Mariupol residents and the troops] knew what was happening in the city. The only [journalists] who stayed there were Associated Press correspondents. They could show what was happening in Mariupol and that we could do nothing without the world's help. In fact, I had no desire to say anything. But Chernov said: "Well, someone has to." I went, and we recorded this address in the yard of an apartment building.

As I said, no means of communication were working. At first, we went to the city center: there was a point where the Internet was available. The bombing was going on, we were hiding in small shelters under the stairs, and journalists were sending materials to the United States from their phones. Then the connection disappeared there as well. We started going to the patrol police headquarters, which was the only way to access the Internet. There were often soldiers, guys from Azov, and everyone needed to contact their families to let them know they were alive. I went there and begged them to turn off the Internet on their cell phones so that the film crew could have a better connection – so that people [from all over the world] could know what was happening.

About leaving the town

On March 14, the first groups of Mariupol residents began to leave by transport. It was obvious that the Associated Press had to leave. The plan was that I would send them along with one international organization (I won't say which one). But it turned out that there was no way to send them.

Time was running out. If we don't send them by March 15, there will be no other option. I have my own private car. It was damaged by a Grad [rocket] explosion. I offered to do the following: if the car starts, they will go. I took the battery out of my home. The car miraculously started. We had maybe ten minutes to decide. I took a set of car tools, a bag with some stuff from Donetsk, threw them into the trunk, and we drove off. Well, pretty much into the blue. What would it be like there? I didn't understand anything. I didn't know anything.

There was a long line of cars. Guys in their uniforms [with blue bulletproof vests with the inscription PRESS] got out of the car and ran in front of it – I was driving, and they were running. People see someone in uniform running in front of the car, and that's how they let us through. Mstyslav ran a kilometer, Maloletka ran a kilometer. Then Evgeniy sat on the hood.

We drove to the point where we were supposed to be met. There was no one there. I drove on. When I left Mariupol, I realized that I would not return.