Treason. How collaborators are punished in Ukraine

Ukrainian prosecutors are considering over 7,000 cases of collaborationism. So far, 941 sentences have been passed. Human rights activists believe that the imperfection of the legislation raises questions about the fairness of these verdicts. If left unresolved, the problem will threaten the reintegration of the liberated territories.

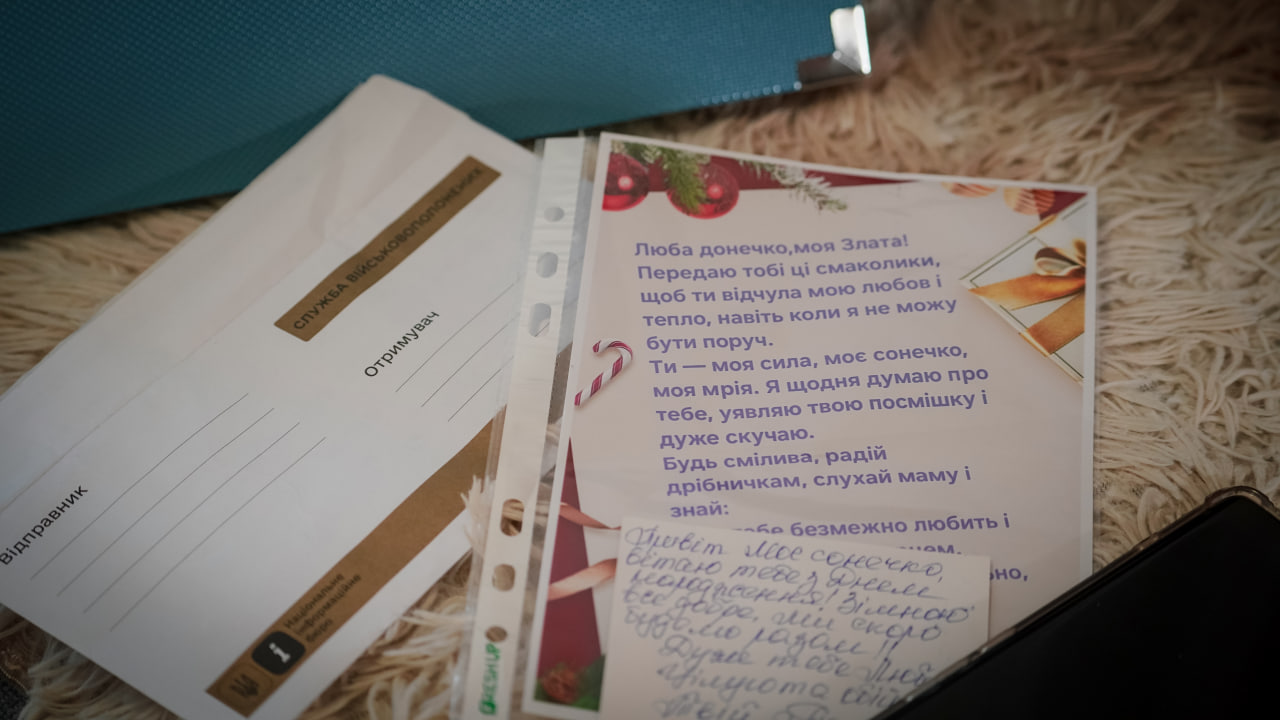

Dmytro Herasymenko, a 35-year-old electrician, lived with his wife in a private house in the northern part of Lyman, Donetsk Oblast. His father and 90-year-old grandmother lived next door. When Russian troops approached the town in April 2022, Dmytro did not evacuate because of his father, who had just suffered a stroke, and his grandmother, who refused to leave.

Soon, Lyman lost water, gas, and electricity. Due to the continuous shelling, the Herasymenko family did not leave the cellar for weeks. They cooked their meals on a gasoline stove. When the town was under full control of the Russians, Dmytro, a high-voltage substation maintenance technician, was offered the job of heading an enterprise that was restoring power supply (and was subordinated to the so-called “DPR Ministry of Energy”). As Dmytro would later say, he agreed because he wanted to help people who were without electricity and also because he was afraid of losing his job: "We were all left without money, without work, without anything. I needed to work to earn money for food, and for medicine for my father."

When Lyman was liberated, Herasymenko, an electrician, was charged with collaboration under Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, part 4: "conducting economic activity in cooperation with the aggressor state." This crime of medium gravity can be punishable by both a fine and imprisonment for a term of three to five years with confiscation of property. Dmytro's lawyer, Oleh Rohov, a resident of Lyman who survived captivity and torture during the occupation, asked the court to take into account the difficult circumstances of his client, and even cited President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as an argument: "...if a person remained a Ukrainian employee of a Ukrainian utility company and, for example, helped to maintain energy supply for people, then you cannot blame such a person for anything."

We were left without money, without work, without anything. I had to work for the Russians to earn money for my father's medicine

However, the court was adamant, and Herasymenko's sentence included confiscation of property, three years in prison, and a 10-year ban on working in his profession.

Same crimes – different punishments

Despite the fact that Russia occupied parts of Ukrainian territory as early as 2014, the concept of "collaborationism" appeared in Ukrainian national legislation only after the start of the large-scale invasion. The introduction of new corpus delicti – "collaboration activities" (Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine) and "aiding the aggressor state" (Article 111-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine) – was adopted in March-April 2022.

As of October 2013, SBU security service investigators were investigating 6,610 cases under Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code, 946 cases under Article 111-2 of the Criminal Code, and another 2,279 cases under Article 436-2 of the Criminal Code ("Justification, recognition of the legitimacy, denial of the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, glorification of its participants"). Most of them are in Kherson and Kharkiv oblasts.

According to experts of the Human Rights Center ZMINA, there are a number of problems in the practice of applying these articles. The main one is that the articles are not worded clearly enough, which forces law enforcement officers to interpret them at their discretion. This, in turn, leads to the fact that fundamentally different punishments can be imposed for crimes of the same nature.

For example, for a shared post on the Odnoklassniki social network, saying "If you are for Russia, then join this group. LET'S SUPPORT OUR GUYS WHO ARE NOW MAKING HISTORY, PROTECTING THE PEACE PEOPLE OF DONBAS AND UKRAINE FROM NAZIS", a court in Kyiv sentenced a person to five years in prison under Article 436-2 of the Criminal Code ("dissemination of materials containing justification, recognition of the legitimacy, denial of the armed aggression of the Russian Federation").

The articles on collaboration are not clearly worded. Law enforcement officers interpret them at their discretion

At the same time, a court in Zhytomyr sentenced a person for sharing a post "We bow to you, Russian soldier" on Odnoklassniki to 10 years' deprivation of the right to hold positions related to the performance of state and local government functions under Article 111-1 of the Criminal Code ("public calls by a citizen of Ukraine to support the decisions and/or actions of the aggressor state").

To identify problems with the legislation and ways to improve it, ZMINA analyzed 691 verdicts in collaboration cases and commissioned the Kharkiv Institute for Social Research to conduct 20 in-depth interviews with law enforcement officers, judges, and lawyers. The results of the study are presented in an analytical report.

Considering the case of electrician Herasymenko from Lyman, who was tried for "conducting economic activity in cooperation with the aggressor state," the experts found that the concept of "economic activity" is not clearly defined in the law, so it is interpreted by investigators extremely broadly and in different ways.

The document quotes one of the interviewed prosecutors: "Sometimes, even under such articles as collaboration activity, <...> employees of critical infrastructure facilities and medical institutions may be subject to prosecution. That is, those who, according to humanitarian law, cannot be held accountable because they have to ensure the vital activity of the population of the occupied territory. <...> now, during the war, there are many emotional actions, and... law enforcement officers are also human beings. Sometimes there is some abuse..."

Small-caliber collaborators

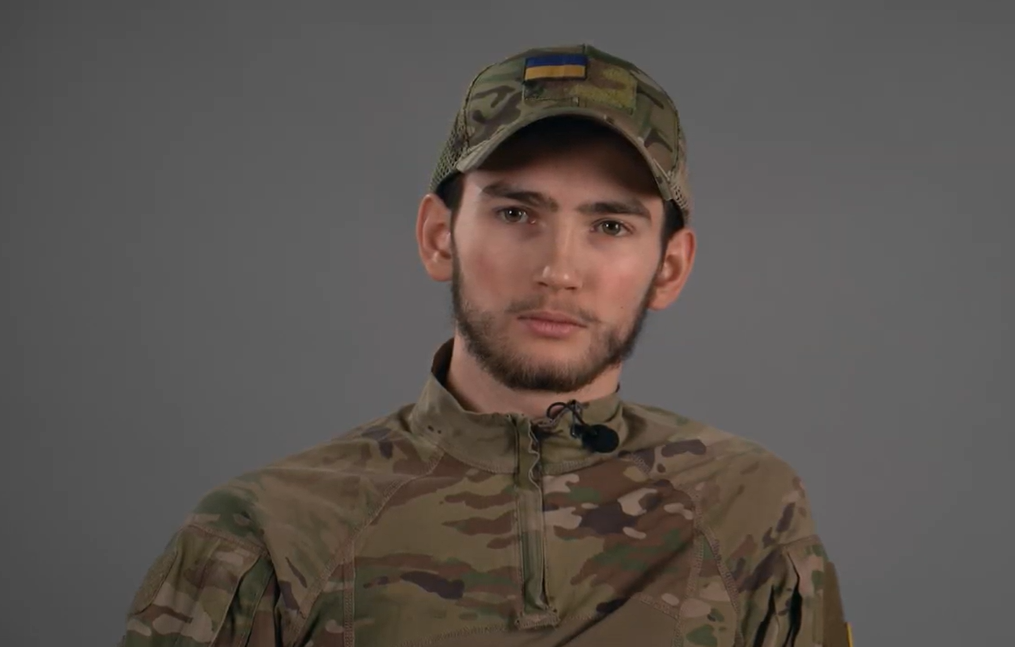

Oleksandr Kobyliev, Head of the Department for Investigation of Crimes Committed in the Context of Armed Conflict at the Kharkiv Oblast National Police Headquarters, notes that according to the Geneva Convention, residents of the occupied territories can cooperate with the occupiers, but only if hired by Ukrainian authorities, not the newly created occupation authorities. The problem is that Russia immediately dismantles Ukrainian institutions in the occupied territories.

According to the Geneva Convention, the occupying power must meet the humanitarian needs of the population, but the Russian leadership, ignoring international norms, deliberately creates a shortage of money and food for locals and thus forces Ukrainians to obtain Russian passports and take jobs offered.

Ukraine's judicial system takes these circumstances into account, Anastasiya Veselovska, a spokeswoman for the Kherson Oblast Prosecutor's Office, assures Life in War. For the prosecutor's office, "it is important not to punish, but to prove guilt or lack thereof," she says. However, it would be a mistake to assume that residents of the occupied territories cooperate with the enemy solely because of intimidation, financial hardship, or legal ignorance. Veselovska notes that for some citizens, collaboration has become a significant social elevator, and cites the story of a Kherson cleaner who served as a school principal during the occupation as an example.

At the same time, the representative of the prosecutor's office cannot recall any high-profile trials of high-ranking traitors. She admits that the SBU and the police manage to detain mostly small-caliber collaborators i.e. those who did not have the opportunity to escape to the east bank of Kherson Oblast or Crimea.

As of September 2023, there were only two acquittals in collaboration cases. According to Oleksandr Kobyliev, there are currently about ten such cases. He suggests that unfair accusations occur due to procedural errors or influence on witnesses.

A spokeswoman for the prosecutor's office admits that the SBU and police manage to detain mostly small-caliber collaborators

However, lawyers defending those accused of collaboration claim that there are many more unjust sentences. In an analytical report by ZMINA, one of the lawyers lists the problems he says he faces in 70% of cases: "It is the inadmissibility of evidence. It is the lack of standards of proof. It is evidence that does not actually prove the commission of an act. It is the testimony of witnesses from the words of third parties."

According to human rights activists, the accusatory bias in cases of collaboration is explained not only by public pressure on the judicial system, but also by law enforcement officers' own beliefs.

There are hundreds of unjustly convicted people

When Dmytro Herasymenko, an electrician from Lyman, was taken into custody, Oleksiy Arunyan, a journalist for Graty, became interested in his case. He met with Dmytro in the Dnipro pre-trial detention center and traveled to Lyman, where he talked to his lawyer, his father, and the town's residents. The result was a podcast episode in which the journalist does not seek to justify Dmytro's actions but rather raises questions about whether three years imprisonment along with property confiscation constitutes a proportionate sentence in this case.

In August 2023, Herasymenko's case was reviewed by the Court of Appeal. The judges ruled that their colleague from the lowest court had rightly found the guilt proven, but had imposed too harsh a sentence, without taking into account that Dmytro had repented, did not publicly support Russia's actions, had an elderly father and grandmother, and had just had a son. Instead of imprisonment, Herasymenko was given two years of probation, and the confiscation of his property and the ban on servicing the power grid were canceled.

ZMINA experts suggest that among the hundreds of people convicted of collaborationism, there are a significant number of those who received punishments disproportionate to their crimes. To address errors, human rights advocates propose removing minor violation categories from criminal statutes, strengthening lustration measures, and considering amnesty legislation to remedy injustices.

Experts believe such steps will not only help equalize the gap between the social dangerousness of the act and the punishment for it but will also promote the reintegration of de-occupied territories and citizens living there.

.png)