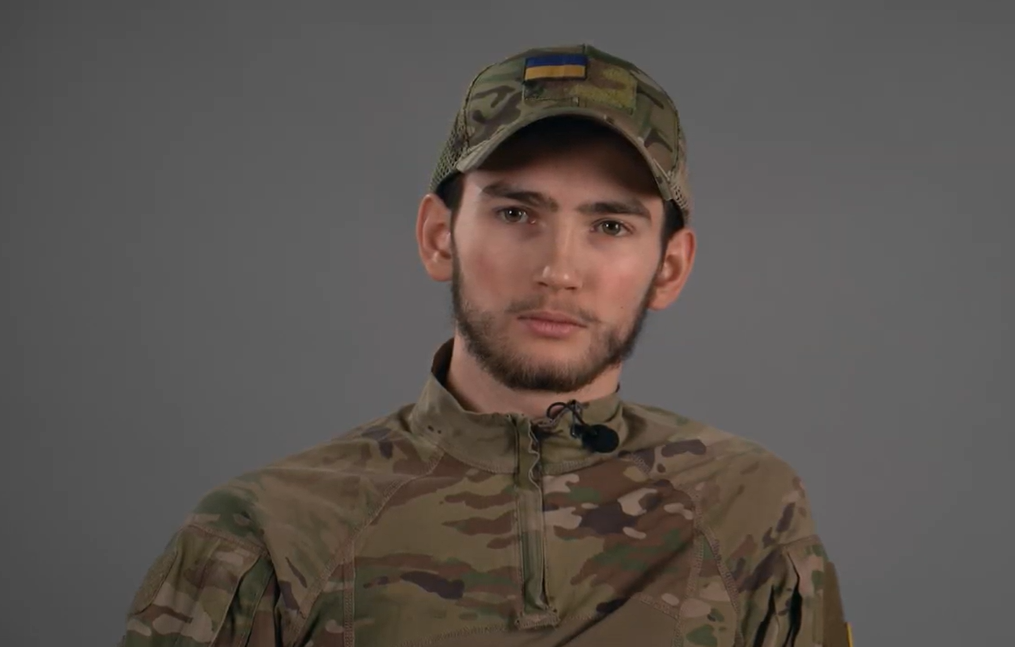

“The Russians said I could be beaten anywhere except the face. Because I am a politician, the face should look normal,” said Mykolaienko, former mayor of Kherson, about his captivity, occupation, and return

On August 24, 2025, as part of a “146-for-146” prisoner exchange, 65-year-old VolodymyrMykolayenko, the former mayor of Kherson, was released from Russian captivity. WhenRussia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he joined the local Territorial DefenseForces, but due to the rapid advance of Russian troops, he did not take part in combat. Heremained in the temporarily occupied regional center and actively participated in peacefulpro-Ukrainian rallies.On April 18, 2022, Russian occupiers unlawfully deprived Mykolayenko of his freedom andheld him in captivity for nearly three and a half years. Journalist and war crimes documenterfrom Kakhovka, Oleh Baturin — who himself spent more than a week in Russian captivity —met with Volodymyr Mykolayenko to talk about life in occupied Kherson in the spring of 2022,his imprisonment, and his return to Ukraine.

You’ve been free for several weeks now and have attended various events in Kyiv. From what you’ve managed to observe during this time, how much have Ukrainians changed since the beginning of the full-scale war?

It’s probably too early for me to give a proper assessment. I’m currently in the hospital, so it’s difficult for me to objectively evaluate the changes in our society. But while I was in captivity, I came to understand that a true nation has been formed in Ukraine — the nation of Ukrainians. Above all, these are people who are fighting for our freedom — both on the front lines and here, in the rear. I was deeply moved to hear about the support for our prisoners of war and about the people who have joined the effort to free our men and women from captivity.

I hope that Ukrainians remain united. I do have some concerns about people who say they don’t care what kind of government we have, as long as there’s a piece of sausage in the fridge. I’ve always said: if your freedom is taken away, your sausage will be taken too — and your bread as well — you’ll be left with nothing. This has been proven by what happened to me and to others who were held in captivity.

I’m also not very fond of those who have temporarily emigrated to other countries. I’m not talking about women and children — I mean men of military age who left and now, from abroad, are telling us how to defend and love our homeland. In my opinion, they should stay where they are and give up their Ukrainian citizenship. If you like Germany or Poland, stay there, but don’t interfere in Ukraine’s affairs. I understand that not everyone can take up arms and fight for the country. When I was handed a weapon myself, I understood that if a battle began, it would likely be my last one — because I’m not a military person at all. But at that time, there was no other choice.

You had no military experience?

At maritime school I only had a 45-day training camp; that’s when I took the oath — back in 1979. I never served in the regular conscript army. So when I was handed a weapon I didn’t even know which side to approach the rifle from. The other guys showed me how to handle it. I had no doubt I would be one of the first casualties. But we understood we had our families behind us. Who else but me should protect my mother, my wife, my daughter, my grandchildren? Likewise, no other man should rely on some Mykolayenko to come and defend Petrenko’s family.

If you can’t defend, you must help the military. My acquaintances asked me if they could volunteer or help financially. Even friends from abroad called and asked where they could transfer money. I said I didn’t know, because I was very afraid many “profiteers” would appear to make money off the war. When I came out of captivity, someone created a Facebook page in my name. Journalist friends told me that from that page, I was supposedly asking for money. Honestly, I would have crushed such “profiteers.” But such people do exist — they are also part of our society.

Did you ever consider leaving Kherson in the first days of the full-scale war?

No. We hadn’t invited anyone into our homes — we were living peaceful lives, building our country. Yes, we dreamed of a much better country, but we were living normally. When people with weapons came to us, I believed we should also take up arms and resist.

When did you sign up for the Territorial Defense?

February 24, 2022. In the morning, my wife said the war had started. There was a column of smoke near the airport — enemy helicopters had set fire to the fuel depots. I said I would pack my things, asked my wife to give me something to eat, and went to the military enlistment office.

The day before, on February 23, I had spoken with our regional military enlistment officer and told him I had a feeling war was coming. I asked him: if war breaks out tomorrow, what should we do? “Don’t stir things up, there will be no war, you’re just provoking conflict,” he said. I insisted: suppose a full-scale war does start — then what? We need to be prepared for it, not just brush it off. He replied, “Well, if something happens, come to our enlistment office, I’ll give you weapons and you’ll go defend Kherson.” When I went to that same enlistment office on February 24, unfortunately, that man didn’t see me — there were some ongoing meetings. Then the duty officer told me the military commissar was avoiding me. I asked what to do then. He said people were gathering at the city Territorial Recruitment Center and Territorial Defense units were being formed. So I went there.

At the city Territorial Recruitment Center, I asked what I should do. They replied, “Go home, pack your things, and come at 12 o’clock. We will form all the units and then send them to the war.” That was in the morning. When I came at 12, there were a lot of people. I stayed there a long time; everyone was probably waiting for some kind of order. Around five o’clock buses pulled up, and someone told me to get on because they would take us to where the territorial defense was stationed.

They took us to the village of Naddniprianske. There, I handed over my military ID, I was enrolled, and they issued me a weapon. While we were settling in, it grew dark. Buses came again, loaded people, and said they would be going to defend the Antonivskyi Bridge. One bus left; two remained and were told to wait. After a while, the first wounded arrived. The Russians were shelling with mortars, and a little later, our artillery appeared and began to return fire. That continued all night.

We spent the night in Naddniprianske, and in the morning, we were moved to Molodizhne, because enemy vehicles had already started crossing the Antonivskyi Bridge. I don’t know why it wasn’t blown up — that remains a huge question for me. If it had been destroyed, enemy equipment wouldn’t have been able to cross the Dnipro. The nearest crossing to Kherson is in Nova Kakhovka, but there’s only a narrow road over the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant and a steep riverbank. Beyond that, the next crossing is only near Zaporizhzhia. The Antonivskyi Bridge remained intact, and large enemy convoys crossed it toward Mykolaiv and Odesa. They say that’s where the Russians were finally stopped — and many of them were taken down there.

What happened in the first weeks of March, when the Russians had already entered Kherson?

First of all, the whole country saw how Kherson met these people — or rather, these inhumans. The city greeted them with massive acts of resistance, showing its attitude toward the so-called “brotherly help,” as the Russians called it when they came to “liberate” us. From whom? From what? From ourselves, apparently. The Russians were clearly dismayed — they hadn’t expected such a reaction from the people. Indeed, thousands upon thousands came out to demonstrate. At first, the Russians stood there frightened, then they began throwing smoke grenades. They fired into the air, detained people, threw them into prisons, beat them.

Then it was my turn. On April 18, 2022, I went to meet someone — but there was an ambush waiting for me. It happened in the city center, around three or four in the afternoon. The person had told me they needed my advice and had important information to pass on. I went — and ended up in captivity for almost three and a half years.

Was that person involved in your capture by the Russians? Who was he?

I’m convinced he was involved. He was also a member of the Territorial Defense. I only know his first name and call sign.

A car sped up toward me, and a man jumped out and grabbed me. He asked my last name. I told him, and they turned me to face the car. “Is it him? It’s him!” They threw me into the trunk and took me to the regional headquarters of the National Police. I immediately called my wife — they hadn’t yet managed to take my phone. I called her, they noticed, and ordered me at once to hand over the phone. My wife realized something was happening, that I was in trouble, that I’d been captured. Later, the Russians told me that within an hour, all the local and national media had reported my detention. I was actually very glad about that — it meant people already knew I was in captivity, and my phone couldn’t be used to lure someone else to a “meeting” and kidnap them too.

Afterward, the occupiers demanded that I call volunteers and journalists, naming specific people, and order me to invite them to meet. Naturally, I refused.

What was the first interrogation like?

They told me I had stayed in Kherson as the head of an underground resistance network, so they questioned me about who was working with me and where the weapons were hidden. They questioned me “with passion.” After a few days, they probably realized that I had nothing to do with any underground leadership. The guys from the Territorial Defense who were also captured must have confirmed that. I really was just an ordinary member of the Territorial Defense — nothing more.

In the meantime, the occupiers decided to “persuade” me to cooperate with them. At first, their offers were “peaceful”: they said they had come here forever and wouldn’t leave, that they needed support from the civilian population, and invited me to join them. I told them that if they needed my advice on how to prepare the city for winter, I could tell them which pipes needed replacing — and they could pay for it themselves. But as for everything else, I refused. I was too old for that anyway.

The interrogations were constant — and included the use of physical force.

Were you beaten?

Like everyone else. There were three or four of them, I think from the FSB. One of them was almost always present during the interrogations — probably a local. He was very knowledgeable about the city, law enforcement agencies, and public life. But I never saw any of their faces.

How long were you held in Kherson?

Sixteen days. On the morning of May 2, 2022, at around four or five o’clock, they sent us to Sevastopol. They said the conditions there would be good — they’d feed us, there would be television, and maybe they’d allow contact with our relatives. They said, “You’ll sit there a month or two, you’ll recognize the ‘new authorities,’ and in a week or two we’ll smash your troops, take all of Ukraine, and everyone will be happy.” And I thought to myself: sure you will — you’ll smash them. They didn’t. But I didn’t sit there a month or two either; I stayed almost three and a half years.

Were any of your acquaintances in captivity with you?

There were five of us sent to Sevastopol, if I’m not mistaken. One of them had previously been a lieutenant in the patrol police. When he was being detained, he jumped — either from the third or fourth floor — broke his arm and leg, and ran for half a block before the Russians caught him. Later, the Russians nicknamed him “Batman.” After that, they brought in another man who had been the commander of my company in the Territorial Defense. He was badly beaten — his body was completely bruised from the torture. Later, they threw in two more members of the Territorial Defense with us.

It turned out that in the neighboring cell was Andriy Putilov, a former member of parliament and ex-head of the Kherson Regional State Administration. But I never heard him.

When the occupiers took you out for interviews on propaganda TV channels in spring 2022, did they warn you about what would happen there, or what you should say?

They didn’t warn me. One day, they gave me a razor and ordered me to shave. By the way, they always said, “You can be beaten anywhere except the face. Because you’re a politician, your face has to look more or less normal.” And that’s what they did: they didn’t hit me in the face. But breaking ribs was normal for them. During my entire captivity, they broke my ribs three times, once in Kherson.

Then they ordered me out. They led me into some courtyard, seated me at a table, and placed two microphones on it — one, if I remember correctly, from REN TV, the other from Izvestia. And Vanechka appeared (the propagandist from Arkhangelsk, Ivan Litomin — ed.). He sat opposite me, and behind Vanechka, a thug stood with a rubber baton. With gestures and facial expressions, he was signalling, “Come on, work. And the rest depends on what you say.” The only thing they told me but didn’t do was take me to Solovyov in Moscow for the show. I replied, “Yeah, let's go, straight to the live broadcast.”

I don’t remember how long the recording lasted. I recall they took me out to that courtyard several times. Once, they lined me up against a wall and said they were going to shoot me. They even asked, “Are you afraid?” But for some reason, I wasn’t — I didn’t feel much fear. I already had two grandchildren; there was someone to leave my family’s future to. The same Kherson man was the one provoking most of all, shouting so much he practically fell out of his trousers. Even some of the FSB officers seemed calmer.

During the filming, the Russians expected me to call on the Armed Forces of Ukraine not to resist, to find common ground with the Russians, and to rebuild the country together. That’s what they wanted to hear. But they never did. My tongue simply wouldn’t let me say such things — I’d sooner have bitten it off.

Later, they took me to the Eternal Flame on the eve of May 9, 2022. They pointed to a plaque with words of gratitude to Russian soldiers for liberating the city during World War II. I said, “Well, thank you. But shouldn’t we also thank the Ukrainian, Armenian, Tatar, or Azerbaijani soldiers?” “You scoundrels! You don’t celebrate May 9th!” they shouted. I said, “How can you say that? May 9th is an official public holiday in Ukraine. People used to come here on that day to honor the memory of the fallen.” “How did they honor it if even your Eternal Flame wasn’t burning?” they asked. I replied, “That’s not our fault — you yourselves set gas prices so high that we would’ve had to spend half a million a year just to keep one burner lit here. I’d rather spend that money on fixing a road.”

Did you speak to them in Russian?

Yes. They constantly beat people for speaking Ukrainian. If you, God forbid, said even a single Ukrainian word — even by accident — you’d get beaten for it. It was an unbearable irritant for them.

What was it like in Sevastopol? Where were you held afterward?

In Crimea, it was a “showcase” facility — Tatiana Moskalkova (the Russian Federation’s Commissioner for Human Rights — ed.) had visited it about a week or two before I was brought there. They also invited Russian journalists to show them how Ukrainian prisoners of war were being “treated.” The facility really was comfortable: they didn’t beat us, the food was decent, there were checkers, chess, dominoes, and a TV with Russian news.

But we stayed in that “sanatorium” for only two days. After that, 48 of us were loaded onto a plane and sent to Voronezh Oblast, to Borisoglebsk. And there, everything followed the classic pattern. They gave us a “warm welcome.”

Were you beaten?

You bet! They showed us who was ‘boss’ here, and then they took us to the detention center and beat everyone there while they were “ taking us in.” They broke my nose and my leg. And then there were people standing around, guards or operatives – about two dozen of them. And everyone has to hit you. I was lucky. I was halfway through, and they stopped beating me. It was painful.

As I listen to you, I recall that other former prisoners said Russians usually didn’t touch those over sixty in captivity. Judging by your words, there were no such “exceptions” for age in your case.

Maybe there were other facilities where they didn’t touch people. But in our first cell, all the men were over 50 — I was 62 at the time. The Russians beat everyone, without asking anyone’s age. In Voronezh, I had a “friend” who took a strong “liking” to me from the very first days. He would make me put my hands on the table and hit them with a baton. My hands would swell so much that I couldn’t even eat. He also systematically beat me on the head. He also liked to shock me with a taser.

I had a story with that taser. It's funny to me now. We were called in for inspection, and the first time they hit me with that taser, I jumped out of my shoes. They stayed on the ground, and I flew — it was so unexpected and painful. Then I somehow got used to that taser. And that Russian beat and shouted. I had the impression that he was getting sexual pleasure from it. And you say they didn't touch...

I even made real friends in captivity — something I never thought would happen at my age. I was in a cell with Andriy, who was about fifty then. When we were taken out, and the Russians asked, “Who do we start beating today?” Andriy would always say, “Start with me, I’m the youngest and the biggest.”

There were other guys, younger ones, who would hide behind my back. There were three of us in the cell. When we went out for a walk or came back, it was usually the first and the last who got hit by the Russians. The one in the middle might get away — or might not. So that guy always tried to stay in the middle between us.

And sometimes they’d take us to the bathhouse. We’d hear them say, “Looks like our old men have gotten a bit too pale.” And then they’d start beating us again.

I even made real friends in captivity — something I never thought would happen at my age. I was in a cell with Andriy, who was about fifty then. When we were taken out and the Russians asked, “Who do we start beating today?” Andriy would always say, “Start with me, I’m the youngest and the biggest.”

There were other guys, younger ones, who would hide behind my back. There were three of us in the cell. When we went out for a walk or came back, it was usually the first and the last who got hit by the Russians. The one in the middle might get away — or might not. So that guy always tried to stay in the middle between us.

And sometimes they’d take us to the bathhouse. We’d hear them say, “Looks like our old men have gotten a bit too pale.” And then they’d start beating us again.

Were there periods in Voronezh Oblast when you were left alone?

Yes. Around the end of July 2022, they eased the regime for us, and the beatings weren’t as severe. Still, I kept getting it. Their inspections required you to spread almost into a full split, hands on the wall. I’m not athletic — I can’t do a split. I still have bruises on my legs from that. They would knock me down until I fell to my knees. They beat me for standing poorly.

At first, the Russians were very cruel. They had been told what scoundrels we are — all Ukrainians — that we abuse their soldiers, castrate them, pour foam into their anuses. They beat us and even set dogs on us. However, later we did feel some easing. When it comes to inflicting pain, the Russians are experts — they’ve practiced it a lot. At some point, I got used to it and was mentally prepared for torture. It was terrifying when young men couldn’t take it and broke down. The Russians rejoiced. How can those young men be restored now? How do you return their self-confidence after all they’ve been through? I don’t know — and that’s very frightening.

When were you transferred from Voronezh Oblast?

We were held there until October 1, 2022, and then transferred to Pakino — a penal colony in Vladimir Oblast, Russia. I stayed there almost until the exchange. From time to time, the Russians would bring in new “batches” of prisoners. It became a bit easier for us then, because the Russians would spend all their physical energy beating the “newcomers.” They always needed to show that they were the masters there, that they could do whatever they wanted to a person.

When I returned from captivity, I started recalling those I’d been imprisoned with. I remembered about forty people. I made a list, tried to find their relatives’ contacts, and called them to say: your loved ones are alive, they’re holding on. I couldn’t find the families of only three prisoners, and that really troubles me. I’ll keep searching.

Did the Russians provide you and the other prisoners with medical care?

I’ll tell you how they “treated” my cellmate Andriy. He’s asthmatic and has breathing problems. Once they took him to see a doctor, and brought him back completely beaten. They threw him into the cell and told us to revive him. We put cold towels on him. When he came to, we asked what had happened.

He said the doctor had given him some medication, and when he left the office, a guard asked, “How old are you?” — “Fifty-one,” he replied. “Then count to fifty-one.” Andriy said, “One,” — the guard punched him in the face. “Two” — another punch. Around seven, Andriy lost count, and the guard told him to start over and hit him with every number. That was their idea of “medical care.”

Were there prisoners the Russians released through exchanges?

Back in Voronezh, around the end of July 2022, the Russians took about thirty prisoners away — we thought for an exchange. But now I’ve learned they were actually sent to other camps.

The exchanges started later, in Pakino. I remember one large exchange. They brought in captured National Guardsmen who had been guarding the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Around late May or early June 2023, they were exchanged — about a hundred people were sent out then. Usually, though, small groups would leave the camp, and we never knew where they were being taken.

When did you find out that Kherson had been liberated?

We practically had no information at all. We tried to ask something about the course of the war — whether any negotiations were happening, whether there was at least a faint hope that the war would end — but no one told us anything. After the New Year, I even asked the guards what their “tsar” had promised them under the New Year’s tree. They just waved it off: “What can he even tell us?” That was their attitude toward their own president.

When I found out about Kherson, it was like a holiday. It was around the end of May 2023. During an interrogation, an investigator told me that Kherson was Ukrainian, but the region was “Russian.” By that time, I already had no doubt Kherson was Ukrainian — I just hadn’t had any confirmation. But hearing about the destruction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant was horrifying.

During one of the interrogations, the Russians kept asking me: “The Ukrainian troops won’t blow up the Kakhovka HPP, will they? They won’t, will they?” I couldn’t understand why they were so obsessed with that question. It felt like the entire interrogation was built to get me to confirm: yes, they will blow it up.

While the Russians held you all those years, did they ever stage any kind of “trial” against you or bring official charges?

No. I wasn’t accused of anything. During one interrogation, they asked if I wanted to recognize the new “authorities.” They added that I hadn’t violated any laws and that they had no claims against me.

Some other prisoners, though, were charged and even taken to court. For example, the commander of a brigade that defended Mariupol. Or my elderly cellmate, whom the Russians wanted to accuse of either storing or trafficking weapons. They beat him brutally and said, “Sign the confession. We’ll get a new star on our shoulder boards for it.” That man was denounced by a Ukrainian who decided to take Russian citizenship. Other guys were beaten so savagely they were ready to sign anything — just to make the torture stop.

Did the Russians warn you about the exchange?

No. On August 20, 2025, they took me out and brought me to the fourth cell. The guys called it the “portal,” because people are sent home from there. They dressed me in a military uniform, photographed me, and forced me to write a statement that I had no claims against the Russians. We understood they were preparing us for an exchange. Although earlier there had been cases when guys were taken to the “portal” and then returned to the cells after some time.

The next day, they returned me to the cell. It was a day of hope. The Russians said Ukraine didn’t want to accept us, so we would remain imprisoned. Well, if we had to stay, we’d stay. I hadn’t even gotten ready for freedom yet. Then on August 23: “Run — out!” They quickly changed our clothes, led us outside, and sent us off. They took me and Dmytro Khiliuk, a correspondent for UNIAN. Two other cellmates were left behind. The worst thing is that, in my opinion, one of them lost his mind. He’s about 26–28 years old — young. He still has a chance to recover, but when he will be taken out of there is unknown. Honestly, if I had a choice, I would have asked them to send Dima instead of me, because he needs urgent medical intervention to preserve his future.

Now I’m trying to make those on the Ukrainian side understand as much as possible that they need to free such young men who are morally broken. Their condition is very bad.

Going back to the period of Kherson’s occupation, were there any traitors or collaborators who surprised you?

No. None of the Kherson locals surprised me. I already had a good sense of what those people were worth. But in captivity, I was unpleasantly struck by one young man who said, “I wish the Russians would capture Kyiv sooner so they’d let us go home.” I said to him, “Who are you to say such a thing? Do you really think other people should be occupied and taken prisoner just so they can let you go free?” Though I do understand — it was hard for him, he wasn’t used to such extreme situations.

Is it true that the Russians offered you to head the occupation administration?

Yes. They placed a large sheet of paper in front of me with all the “vacancies” listed — including that of head of the occupation administration. They told me to write my name next to the position where I’d like to “work.”

Were there many vacancies?

Plenty. The sheet was completely blank. At that time, there were no Saldo or Kobets yet — all of them appeared later.

Did any of the collaborators try to contact or meet with you?

Yes, Kyrylo Stremousov (a blogger and propagandist, representative of the Russian occupation authorities, reportedly killed in a car accident in occupied Kherson in 2022 — ed.). He called me in the first days of April 2022 and said someone wanted to meet with me, assuring me he’d personally guarantee that no one would touch me. I understood perfectly well what kind of “conversation” that would be and refused. By that time, Sashko Babych (the mayor of Hola Prystan — ed.) had already been detained. They told me, “You’ll end up in the pit.” I replied, “Better to be in the pit with Babych than here with you in these offices, in your so-called administration.”

You mentioned that you contacted the relatives of other prisoners. What was that communication like?

The most emotional case was when I spent a long time trying to find the phone number of one prisoner’s wife. I finally managed to and tried to reach her, but she didn’t answer. Eventually, I wrote to her, saying that I’d been imprisoned with her husband and wanted to tell her about him. She replied, “Lies!” She probably didn’t trust me. I answered, “If you think it’s a lie, so be it. But when Mykola gets out of captivity, at least tell him that I called you. Otherwise, he might hear people say he was released and didn’t even bother to call his wife.” Later, I managed to contact his parents.

There were other situations too — I’d call the relatives and ask for a wife’s phone number, and they’d say, “No, don’t call her. She’s already left him.” I also tried to reach the family of a prisoner from Mariupol. To make sure I’d reached the right people and not someone with the same last name, I clarified that his wife had died of COVID. They replied, “His daughter died too. Back in Mariupol. A missile hit, and they were all killed — her too.” So that man sits there not knowing that he’s lost not only his wife but also his daughter. It’s horrifying.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.