“We’ve gone from hell to purgatory, while Western democracies are moving toward hell”— Maria Ressa

Filipino journalist Maria Ressa received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021 for defending freedom of speech. She worked for many years at CNN in Asia, later heading the news department of the Philippines’ largest media conglomerate, ABS-CBN. In 2010, Ressa left traditional media, wrote her second book, and in 2012 founded the online outlet Rappler. The platform focused on fighting disinformation, corruption, and documenting human rights abuses during the “war on drugs,” which President Rodrigo Duterte used to create an atmosphere of fear and impunity. Up to 28,000 Filipinos were killed in the first three years of this campaign.

Because of its criticism of the authorities, dozens of criminal cases were opened against Rappler and Ressa. The journalist could have ended up behind bars at any moment. But in March 2025, Duterte was arrested under a warrant issued by the International Criminal Court — he is accused of crimes against humanity committed during the “war on drugs.” Today, only one case against Maria Ressa remains before the Philippine Supreme Court.

In the podcast “When Everything Matters,” journalist Nataliya Gumenyuk speaks with Maria Ressa about this campaign and the persecution of the media, about the role of tech giants in undermining democracy, about the virus of disinformation and its impact on societies, and about how Ressa works while living between different parts of the world.

Maria, I’m glad to see you not between flights, but in calmer circumstances.

It really did feel like madness. I was constantly on the road — Europe, New York, Boston, San Francisco, and then all over again. I felt like a trained seal that always has to perform. When I finally returned home, I landed right in the middle of a typhoon. In Boston, Hillary Clinton called me “a modern Paul Revere” — someone who must warn of danger. That’s exactly how I’ve felt since 2016. When it comes to the Philippines, I’m Sisyphus and Cassandra at the same time: I push the stone uphill and constantly warn of disaster, but no one listens. And the patterns we see now around the world were already obvious long ago — and the first laboratories of these processes were the Philippines and Ukraine.

Can you explain what happened in 2014–2016? Many people know only about the ICC case against Duterte.

It was an information war. Social media became a weapon — because of its business model. Facebook’s algorithms, designed for platform growth, began dividing people. Imposed metanarratives emerged, and a lie repeated thousands of times became normal. In 2018, MIT published a study showing that falsehoods spread six times faster than truth. The situation has only worsened since. On this wave, in 2016 Rodrigo Duterte won the election. He took the issue of drugs — which was eighth in importance for the public — and turned it into the main metanarrative of fear. This allowed him to launch the “war on drugs,” during which tens of thousands of people — mostly poor — were killed. We were among the first to see how information campaigns win elections, and how the “surveillance capitalism” of tech giants enables manipulation of millions. Ukraine also saw this very early.

We remember the first coordinated attacks on Hromadske. Even our own journalists at the time thought real people were behind them. What happened in the Philippines after Duterte came to power?

To explain that, you need to understand our context. The Philippines lived through 300 years of Spanish colonial rule and 50 years under the United States. We never had a true revolution; we were always inclined to adapt. Within six months of the “war on drugs,” the first victims were the facts. The army and police received almost total impunity. It was a war on the poor, and fear became a tool of control. The system of checks and balances collapsed: parliament and the government were paralyzed, and the courts barely held on. Rappler became the first target. After the president publicly threatened us, eleven criminal cases were opened against us in 14 months. Personally, I received arrest warrants — at any moment I could have ended up in jail. But all this is nothing compared to what Ukraine has gone through.

Duterte is now in The Hague. How did that become possible?

Because no one stayed silent. Families of victims, the church, journalists — everyone documented the crimes. Our journalist Patricia Evangelista wrote the book “Some People Need Killing” — it contains 88 pages of references to Rappler’s materials. It was thanks to documentation that the ICC obtained evidence. There were whistleblower testimonies. In 2025, Duterte was arrested under an ICC warrant — by the current president Marcos Jr. The irony of history: the son of a dictator overthrown in 1986 arrested Duterte, who himself used dictatorial methods.

I want to return to the Marcos dynasty. A generation that was proud of overthrowing a dictatorship now has its heir in the presidential seat. How do you see this?

It shows how quickly things can change. In my book “How to Stand Up to a Dictator,” I warned against a Marcos Jr. presidency. But what we saw was a leader who wants to whitewash his family’s history while also caring about his international image. That’s already a significant difference from Duterte, who didn’t care about external opinion at all. After the change of power, numerous corruption schemes were uncovered: Marcos published a list of fifteen contractors, which triggered a series of investigations and became one of the reasons for the current protests. He restored Rappler’s accreditation in parliament and at the president’s office. Of the eleven criminal cases against me, only one remains in the Supreme Court. And as my lawyer Amal Clooney says, any day could be the moment when I receive a sentence of up to seven years. But this does not change the fact that journalist Frenchie Mae Cumpio is still in prison — jailed under Duterte. Sometimes journalists are killed. We are very far from ideal. I often say that we’ve gone from hell to purgatory, while Western democracies are moving toward hell.

We used to say that Ukraine had a certain “immunity” to Russian disinformation after the shock of 2014. But the virus returns in new forms. You mentioned a “breaking point of the virus.” What do you mean?

The metaphor is very accurate. When people believe a lie, their cognitive system works as if they were sick. Social media has changed our brains. Lies spread faster, women are attacked online far more often, and truthful facts can’t keep up with manipulation. Then generative AI arrived, and the boundary between fact and fiction almost disappeared. A term emerged — “AI collapse” — when the information environment becomes so toxic that machines and people can no longer distinguish reality. That’s why we see illiberal leaders winning elections in 78% of countries worldwide. Ukraine understood this early, but no one wanted to listen — neither to you nor to us. We sounded the alarm because after 2016, elections everywhere became vulnerable. Only Romania dared to invalidate its elections due to distortions caused by TikTok campaigns.

Ukrainian researchers also document massive “feeding” of AI models with pro-Russian content. I read that in Australia, a third of chatbot responses during the elections included Russian narratives.

Yes, and that’s very telling. Pravda Australia was producing over 200 pieces a day — not to persuade voters, but to “feed” algorithms. As a result, every sixth chatbot answer in Australia and every third in the US reproduced Russian propaganda. It’s madness: the information environment is being poisoned not for people, but for machines. And then those machines feed people the content seeded by bot farms.

In Romania, research showed that thousands of pages focused on astrology or travel blogging suddenly began spreading messages about an “energy crisis.” Is this something new or a familiar tactic?

It’s the same old tactic of destroying trust. It’s simply become more technologically advanced. The goal is to create chaos, isolate people, make them doubt their own state. When people lose trust, they cannot act collectively. Civil society weakens — and that is how democracies collapse.

I want to ask about the role of tech giants. Their perspective is very peculiar. How should we interpret it?

In 2016, when I first spoke about the threat, I thought Silicon Valley simply didn’t understand the chaos it had created. We saw it on the frontlines — the data reached us as 90–100 hate messages per hour. But even after the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021, they were barely concerned. They cared only about profit. They stripped people of agency and created an information virus where freedom of speech is fused with danger. At the same time, they forbid their own children from using social media — because they know how toxic it is. And the core issue is that technology giants have abandoned the idea of universal good. They consume colossal amounts of energy, drain the planet’s resources, and build their own escape bunkers. These are fantasies of billionaires driven by the same impunity that political dictators exhibit. In my book I ask directly: who is the bigger dictator — Duterte or Mark Zuckerberg? At least Duterte was elected. But Zuckerberg controls a significant portion of the world’s information ecosystem — and is accountable to no one.

You often talk about smiling, even when describing extremely difficult things. Where do you find optimism?

Optimism comes from action. Ukraine, like us, lives in the trenches. When you’re in a trench, you can’t stand still. We created Rappler as a community of action: journalism is the fuel, and technology is the infrastructure. We built an open system on the Matrix Protocol that now unites 65 local media outlets. It’s a tool that shifts control from tech giants back to citizens. Hope also comes from community. People can see how polluted the internet is with manipulation, and they want something different — a place where they can talk without algorithmic control.

I don’t believe we need to condemn technology itself — the problem is how it’s used. For example, in the drone war, Ukraine creates tools for self-defense, while Russia copies those developments and uses them against you. That shows there will always be creators and abusers.

I disagree with you — I think we do need to condemn technology.

But what matters most are the rules governing its use. The internet can’t be turned off, drone evolution can’t be stopped, artificial intelligence can’t be rolled back. We must acknowledge that inventors must work within clear, civil norms — just like pharmaceutical or medical companies. Almost any technology can be misused. Many innovators work for the common good, but without a code of conduct, someone will always exploit it against you.

Ukraine used drones effectively for self-defense because there was no other way. But it reminds me of the path from the Arab Spring to the Arab Winter. Wael Ghonim, who worked at Google and helped launch the Arab Spring, told me in 2013: “Maria, now the government is using it.” Without rules, authorities easily appropriate the same tools. An example where norms were implemented immediately is CRISPR gene editing technology, which can modify genes at a level where you could literally create a different human being. Thanks to laws passed in the early years, we don’t have “two-headed people”; instead, we use this technology to treat diseases. This shows how critical rules are. But technology still gives us the power of gods without the wisdom of gods — and that can change humanity. It’s already happening. That’s why responsibility lies with governments, especially democratic ones. They must protect people just as they do in construction or medicine. But today we see no such protection in the information sphere, and people are effectively “poisoned.” What can be done? Journalists can do far more — simply by giving people facts. Generative AI leads children into “rabbit holes,” radicalizes via chatbots, because we “fed” these systems all the filth of the internet. Silicon Valley is convinced machines will govern better than humans, but that’s an illusion. The hype around effective altruism and generative AI is unjustified: too much money, too little oversight. Ultimately, it all comes down to people. If societies understand the risks, they can demand better. The United States is one such “breaking point.” But if the West does not respond, if Europe doesn’t clean its information space and stop factories of lies, the world may collapse. The trends are clear: far-right governments come to power because of this information chaos. While there’s still time, we must act.

What actions are most important for journalists now?

First — radical collaboration. All journalists are on the same side. The battle is not against Putin or Trump. It’s a battle against tech giants for a shared reality. We must restore the information space and teach people to distinguish fact from fiction. Second — support for small and medium-sized newsrooms. Their business models are collapsing because advertising has gone to platforms. This is a moment of truth: if within the next 6–12 months we fail to do enough, we will face a long decline.

I want to return to the physical reality of war. In Ukraine we know that without weapons on the battlefield, information campaigns don’t win. How do these two dimensions fit together?

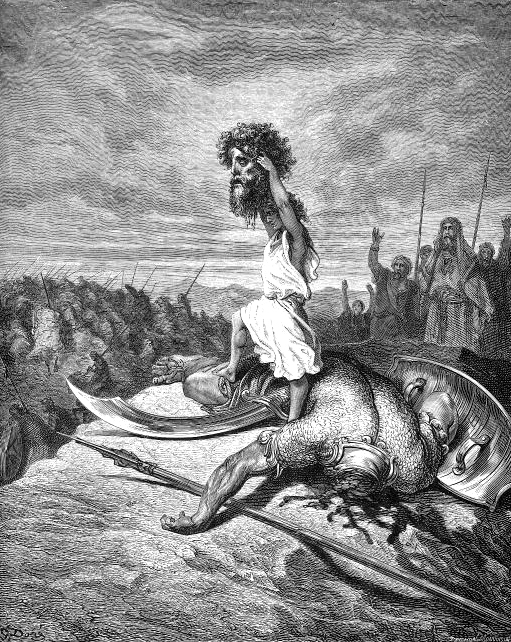

It seems like you’re separating them into two spheres, but they’re connected. Ask yourself: would Russian soldiers have appeared without Russian disinformation? Often the online space prepares the ground for physical aggression. I know this from personal experience: first came waves of lies and online attacks that created the image of an enemy. Only then came the criminal charges and the threat of arrest. It’s the “fertilizer” for future violence. That’s why the information front is not secondary — it’s equal to the physical one. And if you don’t defend it, the war always begins earlier than anyone sees tanks or missiles.

At what stage is your court case now? You mentioned it and the role of Amal Clooney. What exactly are the charges?

I’m almost embarrassed to talk about it because I don’t want the story to be about me personally. But the fact is: the Supreme Court of the Philippines still has a pending case against me for “cyber libel.” I could be sentenced to up to seven years. The absurdity is that I’m being tried under a law adopted after the publication of the article that allegedly violated it. The process is opaque. Whenever I need to leave the country, I must request special permission. Amal says plainly: a decision can come at any moment. And this is telling. Rights that are taken away don’t return automatically. You have to win them back. The same applies to countries: if Ukraine had received enough resources in the first year of the war, perhaps it would have already won. We live in a moment when nothing can be postponed — neither in the physical nor in the virtual world.

You spent two decades working at CNN, opening bureaus in Manila and Jakarta, and then returned home to found Rappler. Why?

After 20 years at CNN, I felt I wanted to build something of my own, not just tell stories created by others. I became head of the Philippines’ largest broadcasting company — ABS-CBN. Thousands of journalists worked there. Those were six strong and important years. But it became clear that the future was online. Traditional media were sending their youngest or least experienced journalists to the digital side. I wanted the opposite: to put the best where the new public sphere was forming. In the Philippines, the median age is 23. For six years in a row, we were global champions in time spent on social media — even with very slow internet. So I left ABS-CBN, wrote a book, and with a team founded Rappler. The idea was simple: social media should serve the good, and technology should help people understand the world. The irony is that at the very moment social media began generating huge profits, they also became most dangerous.

How do you manage to live in several countries and work across time zones? It’s exhausting. What’s your practical advice?

Honestly? I use technology when it helps, not when it harms. In New York, our meetings start at 8 p.m. and last until 2 a.m., and in the morning I’m at the university. In Manila, I work on local time. And, of course, I spend far more time on planes than most people. And if I speak to an audience of 150 people and even twenty feel something and want to act — it’s worth it. My simplest advice: sleep on the plane. Jetlag is a choice. Once you land, stay awake until evening, don’t fall asleep earlier. It sounds minor, but it really preserves your energy.

You received the Nobel Prize together with Dmitry Muratov. Ukrainians have mixed feelings about Russian liberals. What was your interaction with him like?

He always seemed like a “warm bear” to me — someone who hugs firmly. I didn’t know him well, but we stood together on the Nobel stage. My college friend from Russia helped me notice some things I hadn’t seen. In his speech, Putin is barely mentioned, and Ukrainians feel this. But I’m not going to judge him without understanding the full circumstances of his life. Every culture has its boundaries — Filipino, Ukrainian, Russian. I only shared with him my own approach: if I couldn’t speak openly, I would shut down Rappler.

Why is Ukraine important to you? Why do you follow what happens here?

In Southeast Asia, many think this is “not our war.” But Ukraine is on the frontlines of physical struggle, just as the Philippines is on the frontlines of the information war. You show the world the limit to which a society can go in defending freedom. It’s important for Filipinos to see how far you are willing to go. Because sooner or later, every country must answer the same question: will you take up arms to defend your own freedom? Where is the line after which humanity is lost?

If we lose the battle for truth, we lose the battle for democracy. I wanted people at home to hear that.