"They wanted us to break down and beg to surrender Kherson." How Russians terrorize civilians with drone attacks

The past year in the de-occupied territories of the Kherson region has become a period of real terror from the sky for the civilian population. Mass and systematic drone attacks on people have not only intensified but have also become a round-the-clock phenomenon. In August and September, Russians attacked the Kherson region with drones at an average of more than 2,500 per week. In just the first seven months of this year, 847 civilians were affected by these attacks — 79 of them killed, according to the Regional Military Administration. People, animals, civilian and medical transport, and infrastructure are targeted; banned antipersonnel mines are scattered on roads and in parks. The United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine qualifies this conduct, among other things, as a “crime against humanity in the form of forcible transfer of population” — since drone terror has forced thousands of people to leave their homes. How Ukrainian civilians are forced to survive under conditions of being hunted from the sky is described in this article, prepared in partnership with the Public Interest Journalism Lab (PIJL). The testimonies of civilians were collected within the PIJL project The Reckoning Project.

The past year in the de-occupied territories of the Kherson region has become a period of real terror from the sky for the civilian population. Mass and systematic drone attacks on people have not only intensified but have also become a round-the-clock phenomenon. In August and September, Russians attacked the Kherson region with drones at an average of more than 2,500 per week. In just the first seven months of this year, 847 civilians were affected by these attacks — 79 of them killed, according to the Regional Military Administration. People, animals, civilian and medical transport, and infrastructure are targeted; banned antipersonnel mines are scattered on roads and in parks. The United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine qualifies this conduct, among other things, as a “crime against humanity in the form of forcible transfer of population” — since drone terror has forced thousands of people to leave their homes. How Ukrainian civilians are forced to survive under conditions of being hunted from the sky is described in this article, prepared in partnership with the Public Interest Journalism Lab (PIJL). The testimonies of civilians were collected within the PIJL project The Reckoning Project.

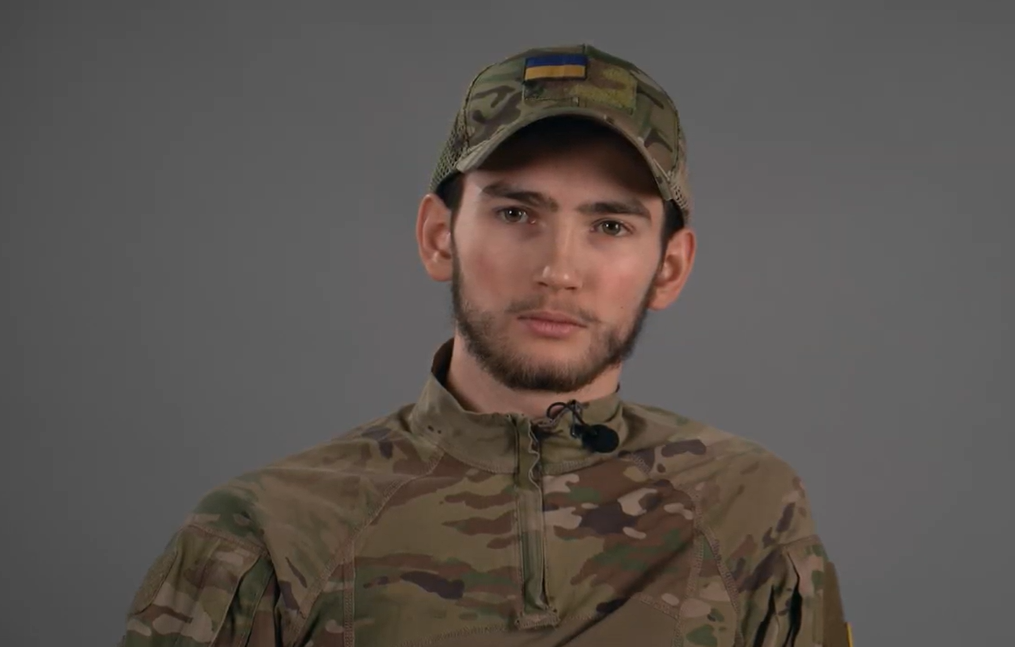

The private house of 66-year-old Tetiana Karmazina is located quite close to the Dnipro River in the Dnipro district of Kherson, also called “Warfield.” On March 30, 2025, the woman went outside to look for her dog, which had run out through the gate. She did not hear the sound of a drone’s engine. But when she reached the nearest intersection, she noticed a drone above her.

“It was either on the roof of a house or on a tree — and as soon as I came out, it immediately took off. I saw a red light and immediately realized that a bomb would be dropped. And that’s exactly what happened,” recalls Tetiana.

The explosive fell directly at her feet. Her right foot was torn off, and her left was badly mangled by shrapnel. Tetiana had left her phone at home, so to save herself she had to crawl back to her house.

“I probably crawled for an hour and a half. The dog came to me at the gate, didn’t recognize me, and started biting my hands,” the woman recounts. “The gate was locked; I couldn’t open it for a long time. Then I still had quite a way to crawl from the gate to the house, but I made it.”

For four months after the injury, she had to stay in a cast. She is still working to rehabilitate her left leg and can already stand on it a little. Soon she will go to Mykolaiv to begin the process of fitting a prosthesis for her right leg. Until recently, the pensioner moved around her home by sitting on the lid of a bucket and pushing herself forward with one leg — an improvised device she invented herself. Before the injury, Tetiana walked 10 kilometers every day — something she now greatly misses. Forced to spend whole days at home, she reads a lot. After the attack, Tetiana moved to a safer part of the city. She says that many of her neighbors do not leave the dangerous district because they are afraid that looters will rob their homes.

Forty-eight-year-old Nataliia Derhach lived until recently in the settlement of Antonivka, located on the bank of the Dnipro. On January 12 at 8 a.m., she went out to walk her dog and heard buzzing on one of the streets. She looked up and saw two drones, then ran to hide behind some trees.

“I ran behind them, curled up, and shielded the dog with my body. They hovered above me for about three or four minutes. They clearly saw that I was a woman with a dog, that I was covering the dog with myself. But that didn’t stop them. My mistake was that either I or the dog moved. The first drop was to my left; I was very lucky that there was a cemented road beside me, and the bomb fell into the ground beyond it. I didn’t hear the second one at all. I just immediately started bleeding,” says Natalia.

As a result of the explosions, Natalia was injured almost all over her body: her torso, arm, both legs, and head. She suffered a concussion. The dog was also wounded. After this, Natalia and her husband moved to a safer district of Kherson.

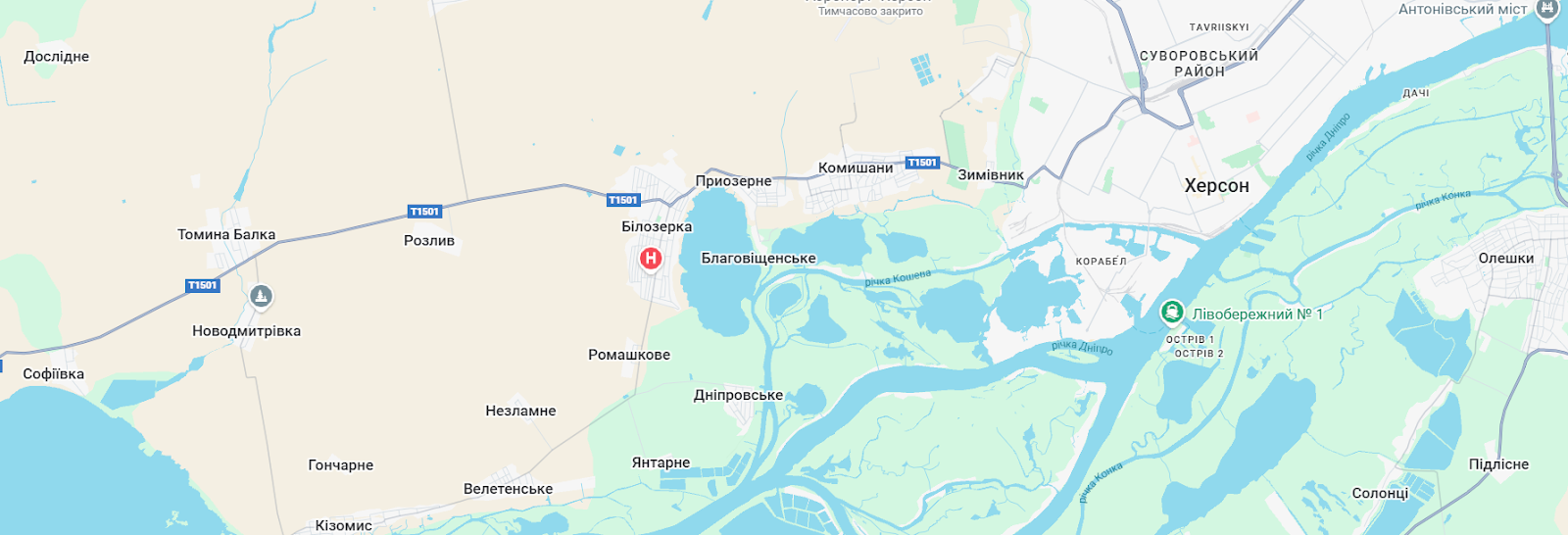

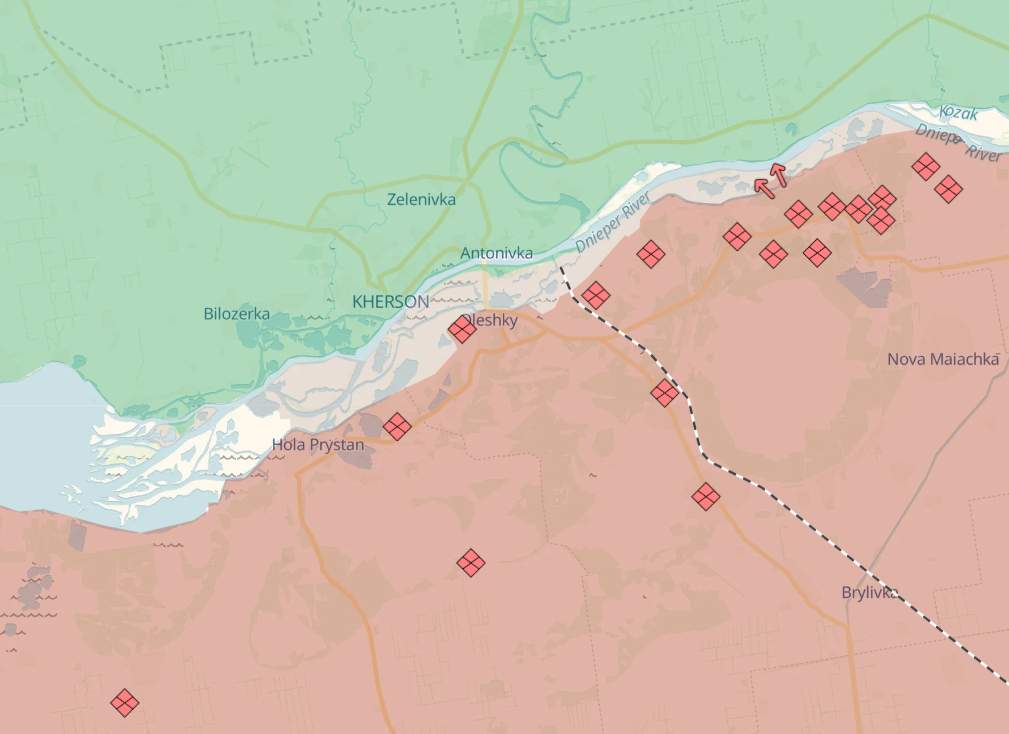

The Red Zone

The Dnipro district and Antonivka, where Tetiana and Natalia lived, are located in the so-called “red zone” of Kherson region. This territory includes part of the regional center and the riverside villages: Sadove, Bilozerka, Pryozerne, Komyshany, and others.

They are separated from Russian positions only by the Dnipro River. This allows the Russians to continuously shell the areas from which Ukrainian forces drove them out in November 2022. Over the past year, drone attacks have multiplied many times. People say they literally cannot leave their homes without risking their lives.

Russians began to use UAVs on a mass scale in late summer and early autumn 2024. They regularly publish their “hunts” on social media, claiming that they target only soldiers and Ukrainian Armed Forces transport.

In September 2024, an image filmed from a drone appeared on a Russian Telegram channel: a person on a bicycle riding down a country road in Kherson region. The caption stated that a Russian operator had recorded a “Ukrainian Armed Forces soldier” before dropping a munition on him. The author claimed the soldier was severely wounded and that his comrades were unable to evacuate him.

The quality of the image was far from perfect, but 24-year-old Anastasiia Pavlenko recognized herself in it. The young woman had never served in the Armed Forces, she is a resident of the village of Antonivka and the mother of two small children. That day she missed her bus and decided to take a bicycle. Near the Antonivka Bridge across the Dnipro, she noticed a drone flying after her.

“It took off from a roof and started chasing me,” Anastasiia recalls. “I turned my handlebars right and left. Then it realized there was a ditch on my right, meaning I could no longer turn that way. I steered left, and it flew aside, filmed me, and then dropped a munition.”

The explosive hit her and rolled to her feet. An explosion followed. Anastasiia sustained a severe blast injury and later underwent several operations to remove shrapnel. One fragment remained in her leg, forcing the mother of two to move around on crutches, and when the pain worsened, in a wheelchair. Despite lengthy treatment, she still limps. Recently, doctors also found another fragment in her lung.

According to the Kherson Regional Military Administration, in the second half of 2024 the most vulnerable villages were those on the outskirts of Kherson — Antonivka and Kindiyka, these are the Dniprovskiy and Korabelniy districts of Kherson. The largest number of drops occurred in September and October 2024, with up to 2,700 drone attacks recorded each month. During the second half of 2024, 47 residents of Kherson region were killed by drone attacks and 578 were wounded, including eight children.

In 2025, Russian drones began reaching the center of Kherson as well. Yet the riverside zone remains the primary target. The frequency of bomb drops continues to rise.

In the first seven months of this year alone, Russians used 16,322 strike drones of various types against the de-occupied territories of the Kherson region. A total of 847 civilians were affected, 79 of whom died. Seven hundred sixty-eight people were injured, including 11 children, according to the Kherson Regional Military Administration. In August 2025, the intensity of attacks increased sharply — up to 2,500 drones per week targeted the Kherson region. This trend continues in September. Although Ukrainian forces manage to shoot down 80 percent of enemy drones, over the past month and a half drone attacks have still killed 15 people and injured 118.

Types and Methods

Russian troops using UAVs drop not only explosives but also antipersonnel mines banned by the Convention on the Prohibition of Antipersonnel Mines, the so-called “petals” or “butterflies.” In June, President Zelensky signed a decree on Ukraine’s withdrawal from the treaty, which prohibits the use of and obliges its state parties to destroy stockpiles of anti-personnel mines. Russia, the United States, and China are not parties to this convention. Ukraine joined it in 2005. The Baltic states — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — as well as Poland and Finland, which shares a border with Russia, have also begun their withdrawal from the treaty. Ukraine’s Foreign Ministry stated that these countries were forced to reconsider their participation in the Convention due to Russia’s armed aggression.

Forty-six-year-old Kherson resident Oleksandr Perederei has been evacuating people, the bodies of the dead, animals, and belongings from the red zone in his private SUV for several years. Twice, while driving along ordinary public roads, he ran over these “petals.” The first time was on April 20, 2025, in Antonivka, when he was evacuating two families. The inconspicuous mine was lying on the road.

“As soon as I entered Antonivka, I drove 300–400 meters and hit a mine. It happened right in front of those people. My wheel was blown out, and I replaced it with the help of those I was evacuating. We worked quickly — one unscrewed the wheel, another tightened the jack. We did everything in a hurry under the drones,” the man recalls.

The second time he ran over an antipersonnel mine was ten days later, on the highway near the Antonivka Bridge.

“I was going fast, and the blast tore off my fender, door, bumper, and wheel arch. The car was badly damaged,” Oleksandr recounts. “They even repaint them specially to match the color of the road or soil, depending on where they are dropped. They know the soil color from drone video footage. On the ground, they are very hard to spot.”

That time, fortunately, only the car was damaged. But antipersonnel mines also take lives. According to the Kherson Regional Military Administration, since the beginning of this year three people have been killed by “petals,” and another 53 injured.

Despite the danger, Oleksandr continues evacuating people.

Forty-four-year-old Kherson resident Olha Chernyshova is convinced that drones primarily hunt people. If no person comes into the operator’s view, he drops explosives on houses or cars. Olha lives in Kherson, near the Dnipro River. In September 2024, Russian drones dropped explosives on two of her cars.

Repairing the vehicles cost Olha nearly 100,000 hryvnias (about $2,500).

According to residents’ observations, last year drone operators were still practicing, honing their skills. For this, they could pick anyone — person or animal.

Nataliia Derhach, who runs an animal shelter, recalls that in October of last year she had to evacuate a wounded dog and the body of a killed one from Antonivka.

“Two dogs were sunbathing. A drone dropped a little bomb on them. They were completely different — one dog was badly injured, and the other was practically torn apart,” the woman recounts.

What’s in the explosives

Residents of Kherson have noticed that the munitions dropped from drones wound people in different ways. Nataliia Derhach suffered multiple mine-explosion-type injuries on the left side of her body, a concussion, and barotrauma.

“The trouble with these drones is that nobody knows what they’re filling them with. On my left side I have ragged wounds — fragments went in and stayed there. And in my right leg a fragment went in and basically exploded inside,” Nataliia says.

Tetiana Karmazina had her right leg amputated below the knee. Her left lower limb has a complex fracture. From the pattern of injuries, she concluded that her legs were hit by an explosive packed with nails.

In 2025, Russians increasingly began using fiber-optic tethered drones that are not susceptible to electronic warfare countermeasures (EW). Drones also started changing flight altitudes so that people have less chance to escape.

“They fly very high, to about 400–500 meters, and when they see a target they suddenly drop down. You only start to hear it when you can clearly see it — unless you can reach out and touch it with your hand,” says Nataliia Dergach.

Residents also describe a double-strike tactic: drones often arrive in pairs. After one drone drops an explosive on a person, the second loiters to prevent anyone from helping the wounded or recovering the body. Because of this, emergency services — police and ambulances — cannot always respond to calls.

Medics go to calls wearing helmets and body armor — this is mandatory, says 65-year-old paramedic Oleksii Alferov of Kherson emergency services. He is currently on unpaid leave because even after several months of sick leave he still limps and is treating the consequences of a drone strike on an ambulance. On April 17, 2025, his crew received a call in the Dnipro district of Kherson — very close to the riverbank. Passersby had called medics for a person struck by a drone. Oleksii and the driver arrived at the scene, placed the wounded person on a stretcher into the ambulance, and set off for the hospital. They had driven roughly 300 meters from the call site when an explosion occurred. The medic felt sharp pain and saw blood flowing. He sustained a severe multiple mine-explosion injury.

“Most likely that drone was in waiting mode,” Oleksii says. “It was a direct hit on the vehicle, into the passenger compartment. The car was destroyed, you could say utterly ruined. The driver was injured slightly less, but he was hurt too.”

Oleksii is convinced the operator intentionally struck medical transport — the vehicle bore clear markings. A taxi driver who happened to pass by took Oleksii and the driver to the hospital. The patient was picked up and transported to the medical facility by police.

Oleksii Alferov was awarded the “For Saving a Life” medal by the president on Independence Day. He plans to return to work in October. Given his injuries, he is unlikely to drive an ambulance again and will most likely take calls from dispatch.

Russian drones hunt not only by day but also at night, using thermal imagers. In Kherson’s riverside zone there is no safe place or time. Public transport does not operate because it has been destroyed by drones. People are also afraid to drive their private cars. Because explosive drops often occur near power substations, many homes are left without electricity and communication problems arise. People are forced to leave their homes. Some residents still remain in the riverside zone, but it is gradually turning into a wasteland. Since de-occupation in November 2022, regional authorities have evacuated more than 47,000 people from Kherson and the surrounding districts, the regional military administration reports.

At the end of August this year, Russians tried to paralyze a vital transport artery of Kherson region — the M-14 highway between Kherson and Mykolaiv. Drones began attacking civilian cars traveling that road. Kherson authorities together with the military deployed every possible countermeasure — EW, anti-drone nets stretched along the road. Traffic resumed, but nobody guarantees complete safety.

Hunting the defenseless

Social institutions are also being evacuated from the riverside zone. Until December 2024, the Kherson regional oncology dispensary operated in Antonivka and served 34,000 cancer patients in the region. But from autumn 2024, Russian UAVs began arriving regularly at the facility, which overlooks the Dnipro, says its director Iryna Sokur.

At first, drones hunted public transport and people at bus stops, the doctor says. Later they targeted individuals and private cars anywhere. They even began dropping explosives onto the hospital parking lot.

“The number of our staff who came to work by their own cars kept decreasing, because their vehicles kept getting into the damage zone. Our parking lot used to be full, so the drops began,” Iryna explains.

In autumn 2024 a patient of the hospital was seriously injured when a drone hit a car. On November 26, 2024, a lab technician from the oncology dispensary was killed. Nurse Tetiana Starostenko witnessed it. Tetiana had finished her night shift and went outside at about 8:00. She was already used to first looking at the sky and saw a drone chasing a car heading toward the hospital.

“I saw a man driving at high speed, the drone was after him. When it caught up to the car, it dropped a bomb — it hit the rear hood. The car stopped. When I went over, the man was screaming terribly, it was awful to watch. And my colleague was lying dead in the front seat. A fragment pierced through the seat,” she remembers.

Iryna Sokur says such events demoralized the staff. After December 2, 2024, public transport completely stopped running in the Antonivka district, where the oncology center is located, so the team decided to relocate. “In their Telegram channels the Russians wrote that there were military personnel there,” Iryna says. “But we never had anyone there except oncology patients. And our oncology patients are mostly elderly people.”

Why are they doing this?

“I was walking down the street, a man was pushing his wife in a wheelchair, and a drone started flying after us,” recalls Kherson resident Olha Chernyshova. “We ran a block down — I, he with the wheelchair — toward bushes and trees to hide, but the drone followed us. It was clear it was hunting.”

Olha calls the hunting of vulnerable people who cannot move without the help of others a new form of terrorism: “This is intimidation —to force people to leave, blackmail, in fact, terrorism. You can see where the drones come from — they fly in from the occupied territories, drop explosives, and fly back.”

This May, a report was published by the United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine. The Commission concluded that Russian armed forces committed crimes against humanity in the form of killings and attacks on civilians with the intent of “spreading terror.” The Commission also found that Russian conduct can be qualified as a crime against humanity in the form of forcible transfer of population, since “the mass and systematic nature of the attacks and the terrorizing of the population forced thousands of people to abandon their homes.”

The report’s authors note separately that the public dissemination of video recordings of attacks and threatening texts announcing further strikes increased public fear, and that the online publication in Russian Telegram channels of footage showing the killing and wounding of civilians constitutes “a war crime in the form of an affront to human dignity.”

“I spent two and a half months in the hospital — every day new victims of drones were admitted. For them this is the most exciting work — to make us break down, to make us beg, probably, for our authorities to give up Kherson,” says Tetiana Karmazina. “But we will not break down, we don’t want anything, we endure everything from them. And they strike only at civilians.”

This article was prepared by The Public Interest Journalism Lab collective, within The Reckoning Project, an initiative of Ukrainian and international journalists, analysts, and lawyers. Since March 2022, the team has been documenting and analyzing war crimes committed during the Russian war against Ukraine.

This publication was prepared with the support of the “Partnership for a Strong Ukraine” program. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the NGO “Public Interest Journalism Lab” and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Program and/or its financial partners.