How Children Live in a City Where Air-Raid Sirens Sound for 20 Hours a Day

According to the Children’s Well-Being Index conducted in 2023 by the Olena Zelenska Foundation and UNICEF, nearly 44 percent of Ukrainian children show signs of potential PTSD resulting from Russia’s war against Ukraine. Airstrikes, fear of losing loved ones, remote schooling (due to the inability to attend classes in person), and the psychological state of parents—who are also affected by the war—have all contributed to this. Life is especially difficult for children living in regions located closest to the front line, such as Sumy. This regional center in northern Ukraine lies just 30 kilometers from the Russian border. Over the past year, Russian attacks with drones, missiles, and aerial bombs on the city have quadrupled. More than 70 residents have been killed and nearly 500 injured, according to the Sumy Regional Military Administration. Air-raid sirens in Sumy sound for up to 20 hours a day.

Palm Sunday Tragedy

The deadliest attack on Sumy occurred on 13 April 2025. Russian forces struck the central streets of the city with two Iskander missiles, killing 35 people. Another 127 residents were injured. Among the dead were minors—17-year-old Oleh Kalyusenko and 11-year-old Maksym Martynenko, who died together with his mother and father.

In terms of civilian casualties, it was the deadliest strike on the city in the 11 years of Russia’s war against Ukraine. The attack took place at the start of the Easter holidays—on Palm Sunday—when many people, including those who were killed, were on their way to church.

The first missile hit the Congress Center, a venue that hosted cultural and artistic events in Sumy. The second missile exploded 140 meters away, in the middle of a street.

The attacks came five minutes apart. This is known as the “double strike” tactic, when the second attack targets rescuers, medics, and civilians who rush to help after the initial explosion.

According to the Sumy Regional Military Administration, the second missile contained a cluster munition—a charge with multiple fragmentation elements designed to inflict mass casualties.

Healing Through Dance

One of the families injured in the Palm Sunday attack is that of Viktoriia Rudyka and her daughters Kira and Elina. That morning, they had been riding scooters and drinking cocoa.

When the explosion occurred, the family fell to the ground as glass, stones, and tree branches rained down on them. Viktoriia and her one-year-old daughter Kira were not injured, but a missile fragment shattered six-year-old Elina’s shoulder and damaged her lung.

Six months after the injury, Elina is recovering through swimming and ballet lessons. After lung surgery, she developed Horner’s syndrome—one of her eyelids is drooping, her pupil is constricted, and one side of her body (the side struck by the missile fragment) no longer sweats. Doctors cannot predict whether this condition will disappear. Two missile fragments remain in her body; they pose no immediate danger but are lodged too deep for doctors to remove. They will likely remain in her body permanently.

Swimming lessons help Elina regain mobility in her shoulder. Ballet classes have improved her coordination.

Elina and her classmates are now preparing a New Year’s performance at the ballet studio. The children rehearsed without electricity or heating. Their choreographer, Anna, lit the floor with battery-powered lamps for the six-year-olds. But parents quickly raised donations and bought a generator for the studio.

This is the reality for children in Sumy who practice dance, as Russia has been deliberately targeting Ukraine’s energy infrastructure throughout the autumn. Power in Sumy is shut off for five to seven hours at a time every day.

Elina chose ballet not by accident—her older sister Veronika dreams of becoming a ballerina. Veronika is 14 and has been studying ballet in Sumy for ten years. Classes did not stop even in 2022, when Russia launched its full-scale invasion and attempted to capture the city. Her mother, Viktoriia Rudyka, remembers that time: gunfire echoed around them, yet the family rushed to dance lessons to avoid losing their minds from despair.

Recently, Veronika was accepted into the Serge Lifar School of Dance in Kyiv and moved to the Ukrainian capital. Her mother and younger sisters visit her on weekends. The family does not want to move from Sumy to the safer Kyiv.

“Sumy is our home. The strikes are terrifying, but where in Ukraine is it not terrifying right now? A missile can hit any city, no matter how far from the Russian border,” says Viktoriia Rudyka.

Viktoriia is currently on maternity leave with her youngest daughter Kira. Her husband was recently killed in the war. An FPV drone struck his car as he was returning from a combat mission.

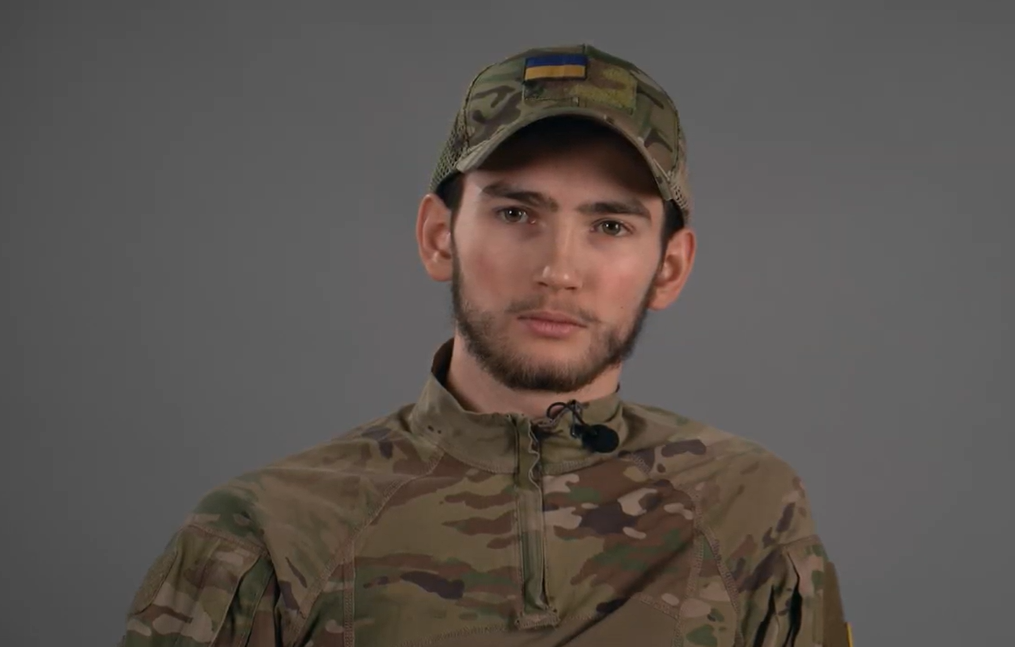

Rescuer of the Year

Thirteen-year-old Kiril Illiashenko was injured in the Palm Sunday missile attack. He was riding in a bus with his mother when a missile exploded in front of it. The driver and several passengers were killed instantly. The bus caught fire, but people inside could not open the doors to escape. Kiril jumped out through a window and forced the door open from the outside.

His bravery deeply moved the residents of a city that had just suffered a tragedy. People brought him fruit and gifts in the hospital. His idol—Ukrainian athlete and Olympic champion Zhan Beleniuk—called him. Later, Kiril received the national award “Treasure of the Nation — 2025” for courage.

During the attack, small missile fragments struck Kiril’s head. Doctors managed to remove some of the shrapnel, but three metal fragments will likely remain in his body forever.

A month after being wounded, Kiril traveled to Croatia for a beach wrestling competition, where he won a silver medal. He was upset—he wanted gold. He competed with a bandage wrapped around his head to cover the wounds, which were still bleeding.

Kiril has been practicing freestyle wrestling for more than six years. His father, Oleksii Illiashenko—a former athlete—trains him. Kiril’s younger brother Matvii and all their friends also attend the wrestling club.

“Shaheds fly all night, explosions everywhere. In the morning, the children are exhausted in school and then they come to my training sessions,” says Oleksii Illiashenko. “I understand how difficult it is for them, and I try to help them relieve stress and stay physically active. Children in Sumy train under these conditions and still win medals at national and European competitions. They are truly brave and strong.”

Kiril dreams of becoming a professional athlete and competing in the Olympic Games. Whether the missile fragments in his body will prevent this—no one knows. His father Oleksii says that his son has already won the greatest award in life—he survived and saved others.

A City Where the Air-Raid Siren Never Stops

The sports school where Kiril trains now has 230 children. Before the war, it had twice as many. Elina’s ballet school had 120 students before the war; now it has only 30.

According to Viktoriia Rudyka, far fewer children can be seen on the streets. Families who had the financial means to relocate to safer regions have already left. However, the number of adults in the city has not decreased, she says.

“In Sumy, you won’t find a free table at a café on Friday evening. There are traffic jams—something we never had before,” says Viktoriia.

There is no official data on the number of children currently living in Sumy—calculations are difficult because of the constant attacks. The Sumy Regional Military Administration only has data on the overall population: in 2025, Sumy has 254,000 residents. This is not significantly different from the number in 2022, when Russia launched its full-scale invasion: 256,000. These figures were provided in response to a request from the Public Interest Journalism Lab.

Authorities say the stable demographic number is explained by the fact that around 30,000 Ukrainians have moved to Sumy from towns and villages on the Russian border that have been completely destroyed by shelling.

Due to the proximity to the border, air-raid sirens in Sumy sound for up to 20 hours a day. The city is struck by missiles, aerial bombs, and drones, and because of the short distance, Russian forces can also use multiple-launch rocket systems. Such weapons reach their targets within minutes, so although the warning system exists, residents often have no time to take shelter. It is impossible for people to spend most of the day in bunkers.

Children’s Lives During the War

Over the 11 years of Russia’s war against Ukraine, 911 children have been killed, more than 2,000 wounded, and roughly the same number are considered missing. Another 19,000 Ukrainian children have been forcibly taken by Russian forces to occupied territories or to Russia itself. These figures come from the Office of the Prosecutor General and the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine.

According to UNICEF, 4.6 million children started the 2025 school year in Ukraine. Because of air-raid alerts and shelling, schooling takes place in a mixed format: on some days children attend class in person; on others — lessons are held online. One million children living near the front line study exclusively online. In certain cities—such as Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv—subterranean schools have been built, mostly funded by foreign donors. However, these projects are extremely costly, especially due to the need for high-quality ventilation, so not all frontline cities have the budget for them.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, more than 2,800 educational institutions in Ukraine have been damaged or destroyed. Not all schools have bomb shelters, and those that do are often too small to accommodate all students at once.

This year, Elina Rudyka started first grade in her hometown. Because her school has a shelter, classrooms for first-graders—60 children in total—were set up underground. All other students, from grades 2 through 11, study online.

Kiril Illiashenko has been studying online since 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began. He is now completing ninth grade. The last time he attended in-person classes was in 2019.

Kiril’s younger brother Matvii is in fifth grade. This year, for the first time in his school life, he and his classmates attend in-person classes once a week; the rest of the time they study online.

Hybrid or fully online schooling has led to problems with socialization and increased negative emotional effects of the war, as noted by UNICEF and the Children’s Well-Being Index report.

Long periods of remote learning have affected children’s ability to concentrate and absorb information. Parents report disrupted sleep schedules, dependence on gadgets, lack of energy, and heightened aggression in their children.

According to the research institution Rating Group, the level of stress among Ukrainian children increased by 10 percent from 2024 to 2025, and more than 40 percent now experience high levels of stress. This stress is directly related to the war.

Children say they worry about airstrikes, fear losing loved ones, and absorb the anxiety and irritability expressed by their parents. According to the study, shared hobbies with parents as well as sports and physical activity help reduce stress. The stories of Elina, who studies ballet, and Kiril, who practices wrestling, are exceptions rather than the norm.