Donald Trump’s Second Term: Year One Comes to an End. What Has It Brought?

The United States began 2026 amid rising tensions both at home and abroad. On January 3, America launched strikes on military and government targets in Venezuela, abducted and removed dictator Nicolás Maduro and his wife from the country, and has already sold the first shipment of Venezuelan oil. Immediately after the military operation in Venezuela, the White House began seriously discussing the possibility of Greenland coming under U.S. control. American officials have not ruled out the use of military force to annex the island, although one scenario under consideration is purchasing it. Trump administration officials have also discussed offering Greenlanders between $10,000 and $100,000 per person, believing this could persuade them to break away from Denmark and join the United States. Denmark and Greenland’s government have rejected these options, hoping instead for negotiations and security guarantees through NATO. Domestically, 2026 is also shaping up to be a decisive year for the United States. Congressional elections will take place in November, and if Democrats win, they may attempt to impeach Donald Trump. The current U.S. president has already urged Republicans to prevent that outcome. At the same time, public dissatisfaction is growing over the Trump administration’s crackdown on migrants. In early January, an officer from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement shot and killed poet Rene Nicole Good in Minneapolis. Her death occurred just four blocks from where George Floyd was killed — an event that sparked nationwide Black Lives Matter protests in 2020.

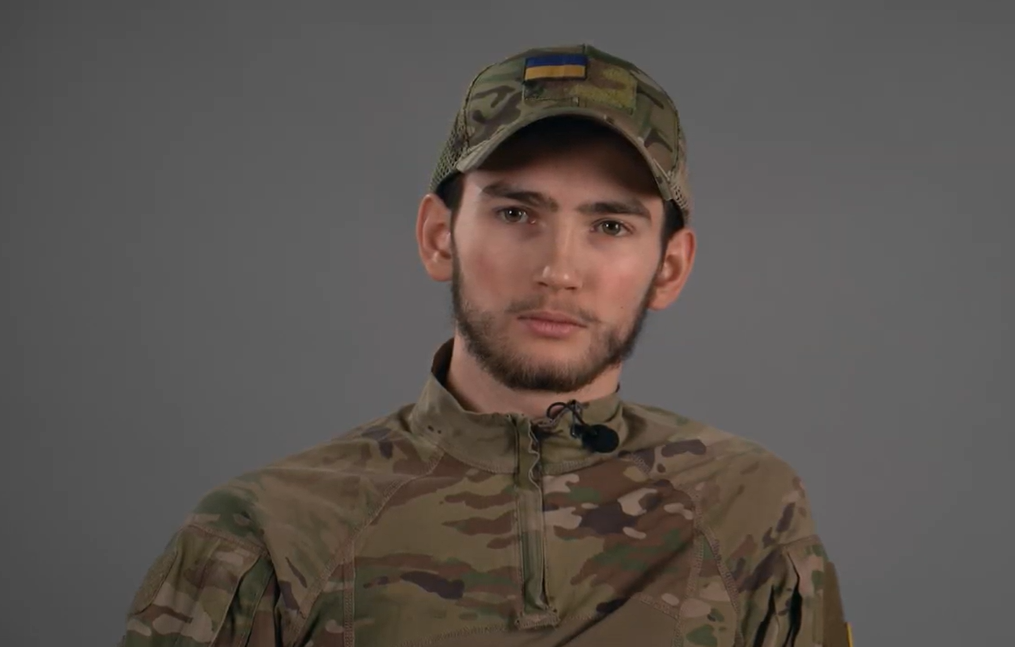

In the podcast When Everything Matters, journalist Angelina Kariakina speaks with journalist Ostap Yarysh about what life in Minneapolis looks like now, whether the killing of Rene Nicole Good could trigger a new wave of civil unrest in the United States, how Americans are reacting to the White House’s actions in Venezuela, and how the U.S. political establishment views “peace in Ukraine at any cost.”

Ostap, hello! I’m glad to welcome you to the podcast, and thank you for finding the time to join us.

Thank you for the invitation — I’m very glad to be part of this conversation.

I’d like to start with Minneapolis, where protests against Donald Trump’s immigration policy are ongoing. These are ICE raids, which recently ended with a city resident being killed by an immigration officer. You were at these protests, so tell us: what is happening there, who is taking to the streets, what are they demanding, and what is the overall atmosphere?

The situation in Minneapolis is extremely tense right now. I was there a few days after an ICE agent shot and killed 37-year-old American Rene Nicole Good. That killing, and ICE’s intensified activity since the start of the year, sparked large-scale protests. During the day, they are mostly peaceful, but toward evening they sometimes escalate into clashes. The increased presence of immigration enforcement is strongly felt throughout the city: in neighborhoods where migrants live, there are posters explaining how to behave if stopped by ICE; in cafés, you can find business cards for immigration lawyers. Some businesses have even posted signs on their doors stating that this is private property and agents may not enter without permission. These events have deeply shaken the city. Everyone is talking about it — from pedestrians to Uber drivers. You can see how the city has organized itself: people are creating Signal chats to track ICE vehicles and warn one another about raids. Particular outrage has been sparked by the federal government’s response. The Department of Homeland Security, ICE, and Trump personally insist that the agent acted in self-defense — claiming the woman was driving her car toward him. But witnesses I spoke with say the opposite: she was trying to flee and turn around, and there was no threat to the agent’s life. This gap between what people saw and how authorities are describing it is fueling the protests even further.

Minneapolis has a special context — it was here that George Floyd was killed (George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was killed on May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis during a violent police arrest — ed.). How connected are the current events to that history? And is this purely a local story, or is the country responding more broadly?

These things are very closely connected. To begin with, Rene Nicole Good was killed just four blocks away from where George Floyd was murdered. It’s the neighboring area — about a ten-minute walk from one site to the other. One of the men I spoke with told me: “Our muscle memory has kicked in.” People really do remember 2020, and they are comparing how the city is reacting now. There is another dimension I only fully understood once I arrived in Minneapolis — the large Native American community. ICE has also been heavily patrolling their neighborhoods and detaining people on the spot, because immigration officers often perceive Native Americans as Latino or as potential undocumented immigrants. Native Americans are now leading part of the protest movement. They say: “Listen, Minnesota — our people have lived here for thousands of years. The federal government of the United States isn’t even 250 years old. And now you’re telling us we have to show documents or prove that we belong here legally?” They find this outrageous, and it adds another deeply painful layer to the conflict. How local or widespread is this story? In reality, the protests have spread from Minneapolis to New York and Washington, D.C. There, they take place mainly on weekends, while in Minneapolis they continue every day. There have also been demonstrations in Chicago, Portland, California, and Texas. So far, this is not on the scale of the Black Lives Matter movement after Floyd’s death, but the tension is growing. Frustration with immigration policy is building — among migrants, local communities, and businesses alike. The only question is what it will turn into over the coming months.

I think it’s important to explain why Minneapolis, specifically. The city has a large community of migrants from Africa — especially from Somalia and the Congo. Donald Trump has repeatedly claimed that these communities supposedly create a criminal environment and that this must be fought. At the same time, I recently listened to an interview with one of Minneapolis’s police leaders. He said that after George Floyd’s killing, the city police went through serious reforms, trying to rebuild public trust. Right now, they are facing staff shortages, and the increased presence of federal forces is essentially undoing those efforts. In the city, people don’t distinguish between ICE and the local police. Everyone is once again seen as part of one repressive force, and that only escalates the situation further. So my question is about Trump’s use of federal forces. He has repeatedly spoken about the possibility of deploying the National Guard or even troops into “problem” cities. How is this perceived in Minneapolis itself, and more broadly within the political establishment? To what extent do other branches of government see such steps as justified?

Minneapolis and Minnesota in general are very liberal. In the 2024 election, people here voted for Kamala Harris, so opposition to Trump’s decisions was expected. ICE’s presence is viewed extremely negatively. As for the local police, when I asked residents, their attitude was somewhat better. But overall, for many people, it all falls under the same umbrella of law enforcement. As for the National Guard — for example, I live in Washington, D.C., the first American city where it was deployed. It still patrols the streets today. This is not ICE: they don’t check documents or carry out raids. They are mostly present in tourist areas or wealthier neighborhoods.

So they don’t really create a direct sense of danger for me personally, but I also wouldn’t say I feel much safer because of them. When the administration claimed this was necessary due to high crime rates, many city residents responded with irony. The National Guard presence on the streets doesn’t bother me much — I don’t feel strong discomfort. Although locals did protest, and some still do, saying this amounts to a military occupation of the city. At the congressional level, Democrats have sharply criticized these steps, speaking about the militarization of the country and the intimidation of society. At the same time, in some cities Trump was unable to implement similar scenarios — for example in Chicago or Portland, where local authorities opposed it. In Washington, however, the city government chose to cooperate with the president.

Let’s return to Minneapolis. Who exactly is coming out to protest, and how radical are these demonstrations? We know that Rene Good, who was killed, was a poet. She also left behind three children. So who are the people in the streets? How organized is this movement, and does it have specific demands?

It’s very mixed. There are so-called observer groups — people with whistles who warn others when ICE vehicles appear, create noise, and, as they put it, disrupt communication between agents. There are large peaceful demonstrations — mostly liberal crowds, many activists, a very visible Native American community, as well as ordinary residents who are simply tired of what is happening in their city. But there are also cases where things move toward confrontation — when people try to approach the hotels where ICE agents are staying. There have been incidents involving barricades. So far, it hasn’t escalated to Molotov cocktails or the kind of riots we saw after George Floyd’s killing and during the BLM protests. Weather is also a factor: the BLM protests took place in May, June, and July. Right now, in Minneapolis, it’s –15 to –17°C, with strong icy winds, and that physically makes protesting much harder. In other words, the tension is there, it’s building, but how exactly events will develop дальше — we’ll see.

In your view, what has Rene Nicole Good’s killing changed? We see ICE’s explanation and the federal government’s response, but has it affected the agency’s actions in Minneapolis? And does this story have the potential to change Trump’s immigration policy more broadly?

In practice — no. ICE’s presence has not decreased, and the government has completely dismissed protesters’ arguments. The official position remains unchanged: the agent acted in self-defense, and Rene Nicole Good allegedly posed a threat by trying to run him over with her car. There are no signs that federal authorities plan to reduce their presence. Instead, the city is trying to act within its very limited powers. ICE is a federal agency, and decisions about it are made in Washington, not at the city level. But after Rene’s killing, Minneapolis did take specific steps to at least partially protect residents. For example, schools were temporarily allowed to switch to hybrid learning. The reason is simple: ICE agents were patrolling areas near schools — in the mornings and after classes — trying to identify and detain migrant parents. People became afraid to even take their children outside. So the city made it possible for families who do not feel safe to study remotely.

That’s very striking. And to what extent is local government trying to stay on the side of residents, unlike the federal authorities?

Here, everything is quite clear. Minneapolis’s mayor is a Democrat and is in open opposition to Trump. Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, who was Kamala Harris’s running mate in the election, has also publicly supported the state’s residents. Local authorities are doing everything they can to distance themselves from the actions of the federal administration and to show that they are on the side of the people, even if their tools for influence are extremely limited.

Let’s shift for a moment to Washington. I’m particularly interested in the political reaction to Trump’s actions. I’ll start with Venezuela. From Ukraine, this operation looked extremely brazen — essentially like a covert спецoperation and a coup. Can we say it boosted Trump’s popularity inside the United States? What did it actually change?

Among Venezuelans, and among parts of the broader Latin American and Cuban communities — yes, the operation did give Trump and Marco Rubio some political momentum. It also strengthened Trump’s standing among Republican voters. But among Democrats, the reaction has been the complete opposite. Democrats acknowledge that Maduro is a dictator, and his removal in itself does not inspire sympathy. But they openly argue that the real goal of the operation was control over oil, and that it was carried out in violation of international law. So Democrats are firmly in opposition. It’s also interesting that even within the Republican Party, there is a segment that is fundamentally against U.S. foreign interventions. Even if they support the idea of fighting dictatorship or drug trafficking, they are принципово opposed to вмешательство abroad. In the Senate, there was even an attempt to limit the White House’s authority: a bill was introduced that would have required congressional approval for any further military action in Venezuela by the administration. Some Republican senators supported that step and even voted to bring the bill forward. But under pressure from the Trump administration, many backed down. At the decisive moment, Vice President J.D. Vance personally came to the Senate and cast the tie-breaking vote against it — so the bill ultimately failed.

That’s an expected partisan divide. But looking more broadly — did this operation shift the overall mood in the country? From here, it seems like a dangerous precedent. Europe is reacting cautiously, Ukraine too. Does it feel inside the U.S. that something has moved? You mentioned the reaction among Venezuelans: on the one hand, they were finally избавлены of Maduro, but on the other, people are being pushed out of the country. It creates a kind of political schizophrenia.

I specifically looked at polling, not just personal conversations. Overall, Americans responded to the Venezuela operation more positively — much more positively, for example, than to Trump’s ideas about Greenland. Several arguments played a role: fighting drug trafficking, removing a dictator, and the reaction of Venezuelans themselves. Many Americans were guided by the images coming out of Venezuela, where people were taking to the streets and celebrating the fall of the regime. That created a sense of moral justification, despite the questionable methods. So yes, in the short term, this operation likely worked in Trump’s favor — certainly more than some of his other foreign policy adventures.

You mentioned Greenland — let’s talk about that. Thankfully, no one has seized it, but the statements alone sound shocking. What six months ago felt like bizarre jokes no longer seems funny: Denmark has reacted, European leaders have reacted. My question is about the system of checks and balances in the U.S. How capable is American democracy today of restraining Trump? Do real mechanisms still exist that could stop him?

During the first year, we saw very little evidence of Congress seriously constraining Trump. Republicans hold majorities in both the House and the Senate, so for the most part they did not go against the president — that was entirely expected. That said, toward the end of the year, the first cracks began to appear. There was growing pressure inside the Republican Party to release the Epstein files, and that triggered a real conflict. We saw an open split within the MAGA wing, including a public confrontation between Donald Trump and Marjorie Taylor Greene, who had previously been one of his most loyal allies and eventually announced she was stepping down from her seat. Another revealing moment was the so-called “28-point plan,” which provoked a wave of criticism in Congress, including from influential Republican senators. Beyond public statements, there were also private calls to the White House from people whose voices still matter there. In my view, that genuinely slowed the process down and forced the administration to abandon previously announced deadlines. So by the end of the year, Congress’s voice — even within the Republican Party — became slightly louder. Of course, on most initiatives they will still stand behind the president, and that is not surprising — that is essentially how the system works. As for Democrats, they tried to use the shutdown as a way to express opposition, blocking Republican votes. The result was the longest shutdown in U.S. history, but strategically it did not deliver the outcome they wanted. Their entire bet now is on the 2026 midterm elections, when the entire House of Representatives and one-third of the Senate will be up for reelection. Democrats hope to regain at least one chamber, above all the House. If that happens, the вопрос of impeachment will likely arise very quickly. Trump understands this perfectly well and speaks about it openly. In a recent speech, he said Democrats would try to impeach him again if they win, and that this must not be allowed. There is about a year left until the elections — and this period, both domestically and in foreign policy, is going to be extremely turbulent.

If we talk about another layer of checks and balances — the confrontation between the federal government and the states — we’ve already discussed Minneapolis, but California is another key case. To what extent can states and cities realistically constrain Trump?

It depends on the specific city and state: not all of them are in opposition. There are many regions that actively support Trump’s policies. If you travel to Texas, Oklahoma, or Nebraska, local authorities there are not restraining the president — on the contrary, they are helping him implement his agenda. Texas, the second most populous state, is a striking example: the governor and local leadership openly back Trump. So when we talk about the system of checks and balances, it operates unevenly. Liberal states like California try to resist, but in other parts of the country, federal policy receives full support. And that is precisely what makes the situation far more complex than the simplistic narrative of “Trump versus everyone.”

Yes — and it’s not only the stance of local governments. Among local populations in many Republican states, support for Donald Trump is genuinely enormous.

Of course, there are major cities — Houston, San Antonio, Dallas — where the dynamic is different, because large metropolitan areas tend to lean more Democratic. But overall, in Texas and other “red” states, a significant share of voters sincerely supports what Trump is doing. When it comes to ICE operations, people say: “Yes, illegal migrants need to be deported — that’s what we voted for.” When they talk about the economy, they point to cheaper gas and say: “We voted for that too.” The same applies to fighting crime and other parts of his agenda. For many, this is not abstract politics — it is the fulfillment of concrete campaign promises. California is a different story. It is a large, reliably “blue” state and a powerful Democratic stronghold. Gavin Newsom (California’s governor since 2019 — ed.) certainly understands California’s symbolic role and, clearly, has ambitions for 2028.

He is already actively building a national profile — on social media, in the press, and through public appearances. It matters to him to show not only Californians but voters across the country that he is capable of openly confronting Trump and has real political backbone. Under the Constitution, Trump cannot run for a third term, but trends within the Republican Party suggest otherwise: the next candidate will likely continue the MAGA line in one form or another. As of January 2026, that scenario appears the most probable — unless, of course, major upheavals occur before 2028, which cannot be ruled out either. So California is not only about Los Angeles or San Francisco. It is an example of an alternative political model for the entire country. Both the state leadership and Newsom himself understand this very well.

Speaking of the Republican Party and its legacy, let’s talk about the so-called “peace deal” that Donald Trump is trying to push Ukraine toward. We see the rhetoric shifting almost weekly: sometimes the lack of progress is blamed on Russia, sometimes on Ukraine. It has become difficult to predict what this will ultimately look like. But just today, we again heard statements about the “final yard,” about supposedly last steps toward such an agreement. My question is: how does this idea look inside the Republican establishment? To what extent is the track of “pressuring Ukraine into peace as quickly as possible,” and sometimes at any cost, supported by old-school Republicans and traditional party figures?

The idea of “peace at any cost” does not have broad support among traditional, old-school Republicans. In fact, they have been among the loudest critics of the so-called 28-point plan associated with the Russian side. For instance, Senator Roger Wicker, chair of the Armed Services Committee, directly described these proposals as Ukraine’s capitulation. Lindsey Graham — one of the Republican senators closest to Donald Trump, with strong personal ties to him — insists that any agreement must be ratified by Congress. It cannot be another “Budapest-style piece of paper.” It must include clear, legally binding security guarantees. There are quite a few voices like this. Many senators argue that peace is only possible if it is fair to Ukraine. By contrast, pressure on Ukraine to “make a deal at any price” more often comes from younger, more isolationist politicians. They are loud, emotional, and highly effective in the media, but they remain a minority in Congress. A textbook example is Congresswoman Anna Paulina Luna, who promotes openly pro-Russian narratives, meets with Russian representatives, and amplifies claims about the “persecution of Christians in Ukraine.” But for every such figure, there are several senators at the level of Wicker or Graham — people who do not make dramatic statements but wield real influence through votes, backroom negotiations, and pressure on the administration. They remain today the main safeguard against a scenario in which Ukraine is pushed into an unjust peace.

Do you also follow visits by Ukrainian government officials to the United States? I’m curious how you see the Ukrainian authorities working with the wing of American politics that can genuinely shape international policy — and, specifically, Donald Trump’s strategy toward Russia and Ukraine. How active is this work right now, especially after the change of ambassador? We know that Ms. Markarova, with her immense experience, has completed her mission, and now we have a new ambassador. From Washington, what does this look like to you?

Of course, the Ukrainian government is trying to use the levers of influence and the connections that were built up earlier, and to capitalize on them. It seems to me they are doing solid work, both through the embassy and through efforts to strengthen cooperation with the U.S. Congress. Ms. Stefanishyna, in particular, is now actively stepping into this role, learning from Markarova’s experience and continuing the groundwork that was already in place. Every week I see her meetings with key players — both in the Senate and in the House of Representatives — as well as her appearances on American television, including conservative platforms. So the effort is clearly there, both from Kyiv and from Ukraine’s representation in Washington. The Ukrainian community is also very engaged. Quite often, when Ukrainians in the U.S. — both long-established diaspora members and those who arrived after the full-scale invasion and are now residents — are asked what they can do, the answer is fairly concrete: call your representatives in Congress, in the House and the Senate, and speak up in support of specific legislation. These may include initiatives on sanctions, the use of frozen Russian assets, or the return of Ukrainian children. This is important to understand, because it doesn’t work this way in Ukraine — but in the U.S., the system is different. Congressional staffers log every call, report weekly to lawmakers, and politicians pay attention, especially because they have to run for reelection. There are real examples where, after a major wave of constituent calls — including in Michigan — a congresswoman who had previously voted against supporting Ukraine changed her position and voted in favor. And there is another crucial point. When I speak with members of Congress about this, they tell me that more than 90% of the calls their offices receive about Ukraine are calls opposing support for Ukraine. Whether this is the result of organized networks linked to Russia, or simply people who for various reasons do not want continued assistance, is hard to say. But the fact is that negative signals are overwhelming — which is exactly why the pro-Ukrainian presence in this kind of advocacy needs to be significantly strengthened.

The point about calling Congress is fascinating. I remember conversations with experts and journalists at the beginning of Trump’s first term. Back then, many things seemed frightening — and now they are materializing. But many people said: “Trump will come, then Democrats will return — that’s normal, the U.S. balance of power works.” They seemed calmer. Now, some of those people are trying to spend less time in the United States, or have left altogether, understanding that even temporarily, this is not the best period for work or academic projects, given what is happening in universities. So the next question is: what about what Trump is doing is irreversible? What won’t the next administration be able to undo? At the same time, I don’t want to sound alarmist and shout, “This is a nightmare!” if Americans themselves believe everything is under control. So let me ask again: is anything in Trump’s policies causing serious concern among Americans?

You can feel the tension rising in the United States. American society was polarized during Trump’s first term and during the Biden administration, but today the polarization is becoming even sharper. We are seeing cases of political violence from both the right and the left: the killing of Charlie Kirk, two agents of the National Security Agency in Washington, and recently Rene Nicole Good in Minneapolis. The spring is tightening, and it is difficult to predict what 2026 will look like — we are entering an election cycle, with the midterm congressional elections ahead. We can expect the trajectory of 2025 to accelerate, and domestic tensions to grow. Moreover, 2026 is symbolic: the United States will mark its 250th anniversary of independence, and Donald Trump has major plans for the celebrations. As for Americans themselves, there is no single view. If you travel to “red” communities, people sincerely say these are the best times since Reagan, since the 1980s — that life and the economy have improved. Their support is genuine. But at the same time, events like those in Minneapolis show that a significant portion of Americans does not agree with the administration’s course. This is a major societal challenge for the United States: finding answers and stabilizing the situation. And for Ukraine, this is also critical, because our situation depends in many ways on what happens in the U.S. So we will keep watching — with anxiety at times, with curiosity at others, sometimes with popcorn — and hoping that for Ukraine, it will not lead to very serious consequences.