What If Trump Wants Goliath to Win?

Original article was published in English as a guest essay in the newsletter of American historian Timothy Snyder, Thinking About….

Note from TS: from time to time on Thinking about... we will listen to other voices on important topics. Nataliya Gumenyuk is a leading reporter on war and politics, known for her work in the Middle East and in Ukraine. Here she reflects on how we think about the Russo-Ukrainian war. The Biblical image from which she begins, of David and Goliath has powerful resonances in our own time. This essay can be read as a discussion of a certain problem in American foreign policy, but also implicitly as a discussion of the role that archetypes and prejudices play in foreign policy.

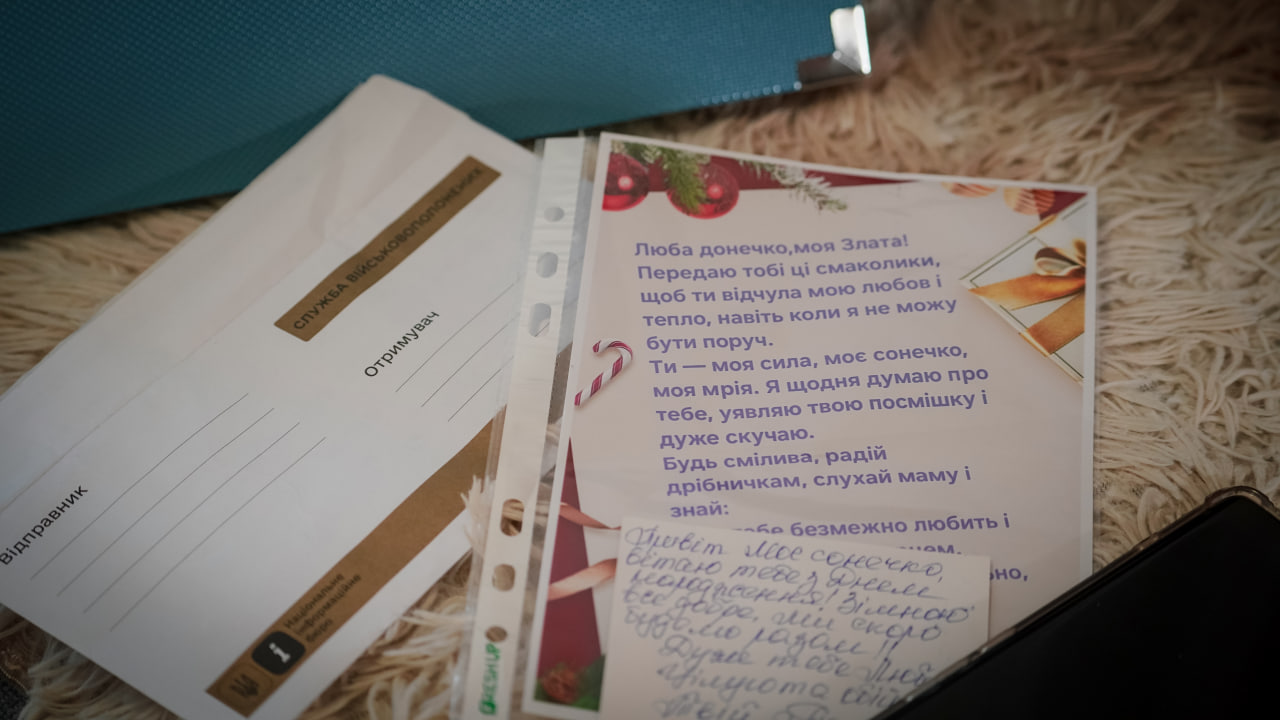

Pretty much every week I notice that Ukraine figures in international news as a David fighting against a Goliath. A Polish colleague just me asked whether the book I’m writing about the Russian war against Ukraine would have the word “David” in its title, since I also write about other things that begin with the letter “d”: decentralization and democratization. I laughed, because for quite a while I have indeed been thinking about the image of David and Goliath in the context of Ukrainian-American relations.

The metaphor of a struggle of David against Goliath tends to resurface each time we have to deal with another burst of so-called “negotiations,” when American leaders say, for example, that the Ukrainian president has few cards, and therefore must make concessions. If Russia is a Goliath, if that image is what matters, then Ukraine’s arguments and indeed the actual correlation of forces on the battlefield do not matter.

On the force of a stereotype, or an archetype, the White House insists (now, as several times before) that Ukraine must enter an agreement which would worsen not only the current battlefield situation but grant Russia things that it could not in fact get without American help.

The classic example of this, which has emerged several times and just emerged again this month, is that Ukraine must cede to Moscow the full Donetsk region, which Russia is not capable of taking. It is the best-defended section of the front line, which of course is why Russia wants American help to get it without a fight. It is certainly possible to imagine Ukrainians accepting a full ceasefire; but this text did not even provide for one, focusing instead only on such concessions to Russia.

We are told that international relations is a realm of interests and logic. But other things are clearly at play, and journalists right now are exposing some of them. But I want to dwell on an underlying issue, the moral issue, or perhaps the psychological issue.

Why Moscow and the Russian war of aggression seem to arouse sympathy in the White House? For those of us who root for David, this can be hard to understand.

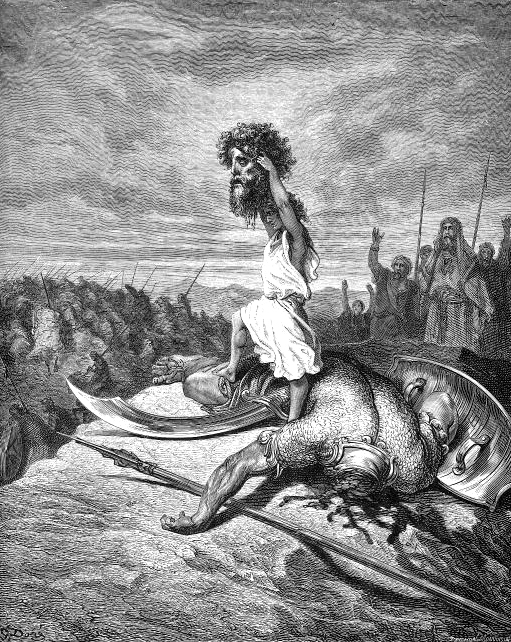

Indeed, for most people, it seems to me, David is an unequivocally positive figure. He embodies the capacity of a small individual to resist a vast and dangerous world. It’s not only about one man; it’s about the idea that good can overcome evil, that something apparently weaker can prevail thanks to confidence, persistence, and intelligence. And indeed, sometimes that does happen. It is not just a wish, it can be a reality. David slew Goliath.

But the question of David and Goliath is not just one of the past few days or months. A year ago, during the 2024 US presidential election campaign, I was writing for American publications. I had the feeling that editors were asking me over and over again for the same article —that I had to make the case again and again that Ukraine, as a David fighting a Goliath, deal with Trump, a man who constantly shows admiration for “Great Russia,” who values the strong, the apparently obvious winner?

All of my answers, back then, were variations on David’s smartness, ingenuity, and determination. At that time, Kyiv still clung to the argument that if Western support were more decisive—if there were specific actions from the West rather than just praise for Ukraine’s resilience—much would change. This was the context in which Ukraine was presenting Victory Plan to both Democrats and Republicans in the autumn of 2024.

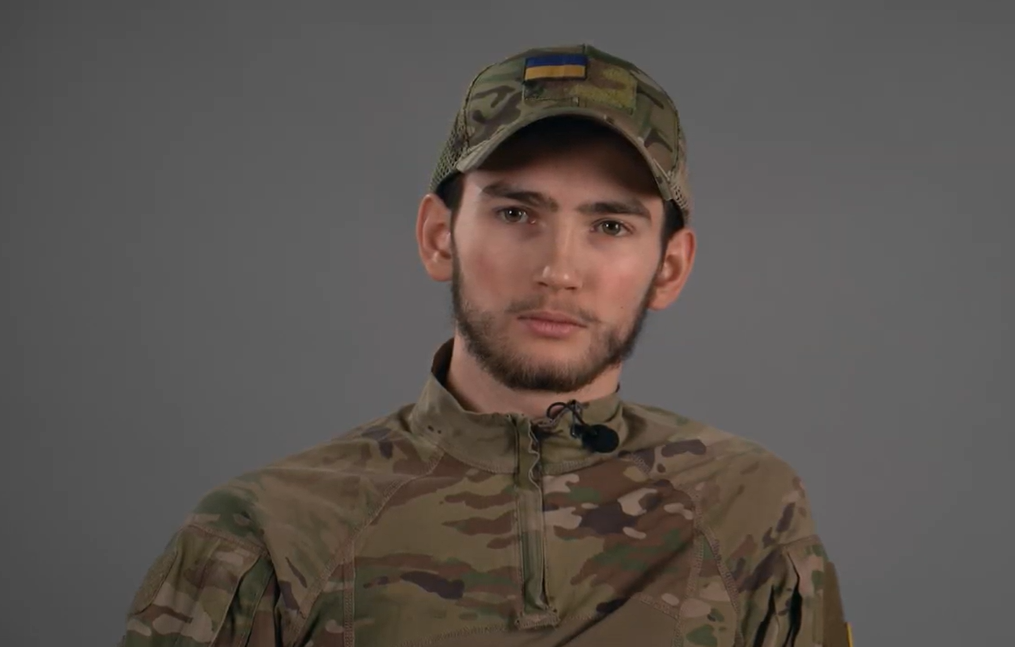

During that campaign, and in the weeks after Trump’s victory, Ukrainian diplomats generally insisted that Trump did not personally dislike President Zelens’kyi. After all, he seemed to perceive Zelens’kyi as a fighter, not a weakling. Ukrainians tended to think roughly the same thing, to see themselves not as a nation of victims but as underdog fighters. Instead of constantly trying to interpret Trump’s moods or adjust to them, Ukraine spent the year working to reduce its dependence on the United States, building its own military-industrial complex.

Then came the Oval Office meeting between Trump and other Americans with Zelens’kyi on February 28th. It was miserable. When Trump said that “Ukraine doesn’t have any cards,” Zelensky replied, quite firmly, that Ukraine was not playing cards—it was fighting a war and dealing with matters of human life. Even though the “card analogy” sounded vulgar, and did really reflect the truth on the battlefield, Ukraine began searching for the “cards” that it it could show Trump, cards that he could see. And suddenly the media mood began to shift.

My American editors, as well as foreign analysts and experts, asked me to explain why Ukraine can win, why it is strong, and why it is the side worth supporting. Throughout the spring, there were numerous meetings—Zelens’kyi with Trump, and J.D. Vance with European leaders in Rome. Global efforts, especially by European countries, were intensifying. Relations seemed to have stabilized somewhat.

Yet when Ukraine actually showed strength on the battlefield, in an unmistakable way, the results were mixed. If Trump wanted to see a “card,” Ukraine definitely showed him one in early June 2025: Operation Spiderweb. This was was a deep-strike campaign carried out by Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) against Russian military infrastructure, including airfields far inside Russian territory. The operation caused an enormous stir in the global defense community and provoked widespread admiration.

Ukraine, small but determined, allegedly inflicted losses of around US$7 billion. and hit roughly one-third of Russia’s strategic bomber fleet.

A few days after Operation Spiderweb, in the United States, I saw how astonished experts in New York and Washington were by the scale of the operation. Goliath had taken a hit. What would follow?

Yet the American president seemed not to notice. And his reaction to Operation Spiderweb, such as it was, seemed to arise not from the event itself, not from what David had done, but from what Goliath had to say about it. After a phone call with Putin, he said that Russia “will have to respond to the recent attack on the airfields,” which I interpreted as blaming Ukraine for “provoking Goliath.” Shortly afterward, Trump wrote that Ukraine should show restraint and not escalate the conflict with Russia—echoing Moscow’s narrative.

In the next moment, the two months between Operation Spiderweb and the Alaska meeting between Putin and Trump, the media space was still dominated by articles about some possible agreement that would “freeze the conflict.” None of this really reflected the battlefield; it was more a reaction to a White House mood. Meanwhile, by now, half of the weapons on the front were domestically produced. Drones had become a symbol of innovation, giving Ukraine a tangible advantage. Yes, Russia was sacrificing thousands of soldiers, advancing step by step, but at that pace—even considering the painful losses of Ukrainian troops—it would take decades to capture the major cities of the East.

Kyiv feared that freezing the front lines would simply give Russia time to rebuild its military strength while Western support declined. This scenario favored the Kremlin, yet rejecting it outright was difficult—Ukraine risked being portrayed as the obstacle to peace, which was exactly the narrative Putin sought. Ukraine consistently said that it would accept a ceasefire.

It was Russia that did not. It consistently rejected a ceasefire, but paid no price -- as if this were natural for a Goliath. Putin aimed to make Ukraine look uncooperative, to shift blame onto Kyiv for “sabotaging negotiations.” In reality, Ukrainian officials were ready to accept a ceasefire in place, but Putin, intoxicated by what he saw as his own successes, which were perhaps largely in the mind of the US president, wanted more. In Alaska Putin met with Trump alone, without Ukrainians, without Europeans. This was itself very significant -- the war of aggression and Russia’s war crimes had isolated Putin until then. During the Alaska summit, talk of negotiations resurfaced, driven largely by Putin’s blatant arrogance. In public Trump echoed Putin’s general line about Russia’s greatness and sympathized with Putin. But Alaska led to nothing. The world could clearly see that Putin was not ready for any genuine negotiations.

After the Alaska fiasco, Trump kept talking about “big Russia,” about the “great side” -- and that was the moment when I realized that for an entire year I had been constructing the wrong argument, sticking to a famous analogy which, although in some respects true, might be even harmful. In the Bible, David does win. But of course in the Bible some people were rooting for Goliath. And what if that is the case now? What if some people simply hate the David figure, because they do not like surprises, they do not like talent, they do not like people working their way up towards the top, towards victory on the basis of merit? What if for somebody like Trump the victory of a small David defeating a big Goliath is irritating because he thinks that the big should beat the small, that the more powerful (or those who are believed to be more powerful) should always triumph?

It is not so much that Trump himself is a Goliath. It is rather that in the tv show of David versus Goliath, he roots for Goliath.

In his comportment towards the Russo-Ukrainian war, Trump does not behave as a statesman with an idea of US interests; it seems that he is driven by personality. His ambitions are not those of American expansionism, but of his own persona, his own power, his own worldview, which he wants the world to reflect.

The David-and-Goliath story is deeply archetypal, and for most people it is hard to imagine anyone genuinely wanting to side with Goliath. We have all felt small at some point; watching a weaker side collect itself to confront a giant speaks to our own desire to exist in history, to take meaningful action, to overcome long odds. To identify with David restores a sense of justice. It reassures us that brute force, size, or bullying are not the final word, and that moral clarity can in fact win. The Biblical story gives hope that the system is not always rigged; that hierarchies can be disrupted; that the powerful are not invincible. It affirms human agency: David wins not because he is larger or physically stronger, but because he is more intelligent, faster, and more inventive. Ingenuity can overturn dominance.

As we go through all this yet another time, as a capitulation plan written by Russia takes on an apparent legitimacy because it is presented by Americans as their own, I am asked again, as so many times over the years: what does Putin have on Trump? Why is Trump so persistent? And perhaps, at last, I found the answer, or at least a meaningful part of the answer. It is not really about domestic Ukrainian politics, the sense that Zelens’kyi is weak because of a corruption scandal. It is not about the recent massive Russian strikes on civilians. I do not believe that the specific moment is that important. The answer lies elsewhere.

The unfortunate reality is this: we are seeing affirmative action for Goliath. We know that Goliath can lose. Wars are unpredictable. Russia has many problems. They could be exploited by consisted US and European policy. David can win. But the whole traditional scheme, the whole moral scheme, the whole archetype of David-versus-Goliath seems itself to be hurting Ukraine.

This US administration seems to prefer a world where Goliath always wins. Or at least a world where David must be told never to pick up his sling.

You can subscribe to the newsletter at this link.