“Less talk about what the White House will think. More action!” — Kersti Kaljulaid

Kersti Kaljulaid became Estonia’s first female president in 2016 and led the country for five years. Trained as a biologist, she worked in both the banking and public sectors and in the early 2000s ran a power plant. She openly acknowledges the existence of a glass ceiling that limits women’s career growth and leadership ambitions. When a woman ignores prejudice and still reaches for top positions, people immediately start questioning her competence, personality and even appearance. For twenty years now, whenever someone asks Kaljulaid who this woman is and whether she can handle such a demanding job, she has replied with the same line: “I always ask in return: do you need a penis to run, say, a power plant? I don’t have an answer to that question — and neither do men.”

Kersti Kaljulaid is a consistent defender of human rights, the rule of law, freedom of speech and democracy. She constantly urges people not to stay silent and to speak out openly against injustice and rights violations. She also spoke out over the disqualification of Ukrainian skeleton racer Vladyslav Heraskevych at the 2026 Olympics. “Honouring the memory of your fallen compatriots is not politics, it’s human,” said Kaljulaid, who now heads the Estonian National Olympic Committee.

In the podcast “When Everything Matters”, journalist Nataliya Gumenyuk talks with Kersti Kaljulaid about sport under authoritarian regimes, the city of Narva on the Russian border and how local attitudes have shifted, NATO’s actions in relation to Estonia, what makes it possible to integrate Ukrainian refugees in Estonia, and what could ensure Ukraine’s energy resilience in the future.

Kersti, you head Estonia’s Olympic Committee and came to Munich straight from the Games in Italy. Thank you for your sincere support for Ukrainian athletes — it means a lot. Why, in your view, did the disqualification of skeleton racer Vladyslav Heraskevych over his “memory helmet” become one of the defining moments of these Olympics?

Heraskevych’s disqualification turned what could have remained a local incident into a global precedent. Of course, the IOC has rules. But where is the line between formal regulations and basic humanity? The Ukrainian skeleton racer didn’t resort to any aggressive form of protest like blocking a route, as happened in the 2025 Vuelta, when protesters with Palestinian flags physically stopped the race and the final stage was cancelled because riders could not finish. That was dangerous.

There were no hostile slogans on Vladyslav’s helmet — only restrained black-and-grey memorial images. It didn’t look like a provocation until the decision to disqualify him made it an issue of global importance.

Naturally, I’m proud that it became a global issue, and I’m proud that things banned in Milan can be spoken about freely in Munich. I’m glad that thanks to YES (Yalta European Strategy), Vladyslav has the opportunity to discuss his act with political leaders. It proves that the voice of truth cannot be silenced with a disqualification.

What does this mean to you personally?

A great deal. Even before the Games began, we warned the IOC that Russian and Belarusian athletes were gradually returning to the global arena. Unfortunately, the Baltic states found themselves in the minority, so now we have to act more subtly, explaining to the sports community what is really going on. And Vladyslav’s case is exactly such an instrument.

I told our Estonian athletes very clearly: we are not going to boycott the Olympics. Instead, we will make blue and yellow our main way of being present — everywhere and in any quantity. This kind of asymmetric action is what the Olympic movement needs today so that the topic of aggression cannot be silenced or brushed aside.

It’s obvious that Ukrainians are deeply disappointed with the decisions of the International Olympic Committee. Ultimately, behind Olympic slogans there are often big money and even bigger politics. We remember 2014 well: Russia hosted the Games in Sochi and just days later launched its invasion of Ukraine. Do you believe the IOC is capable of real transformation? And what goal do you, as head of Estonian sport, set for yourself in that conversation?

Most IOC members come from the world of sport, and for them the interests of the athletes are paramount. They still carry a painful memory of the boycott of the Moscow Olympics in 1980, when more than 60 countries refused to participate because of the USSR’s aggression in Afghanistan. This determination to “save the Games at any cost” makes them deaf to reality. On top of that, they often invoke double standards, bringing up conflicts in Ethiopia or South Sudan.

For us, however, the red line is clear. Russia, a signatory to the Helsinki Final Act, has openly trampled on its own commitments. To demand that Ukrainians compete “on equal terms” with the aggressor is not fair play, it is blatant injustice. Authoritarian regimes are extremely skilled at turning sport into a propaganda tool, buying the loyalty of federations. This degradation of Olympic principles is not just destructive — it is disgusting.

Have you met Vladyslav Heraskevych? Spoken with him?

Yes, I met him on Friday. At the dinner I was moderating, I had the honour of congratulating him on behalf of everyone present. I’m proud of YES’s decision to invite him to Munich — it gave him the chance to explain to opinion leaders what really lies behind his act.

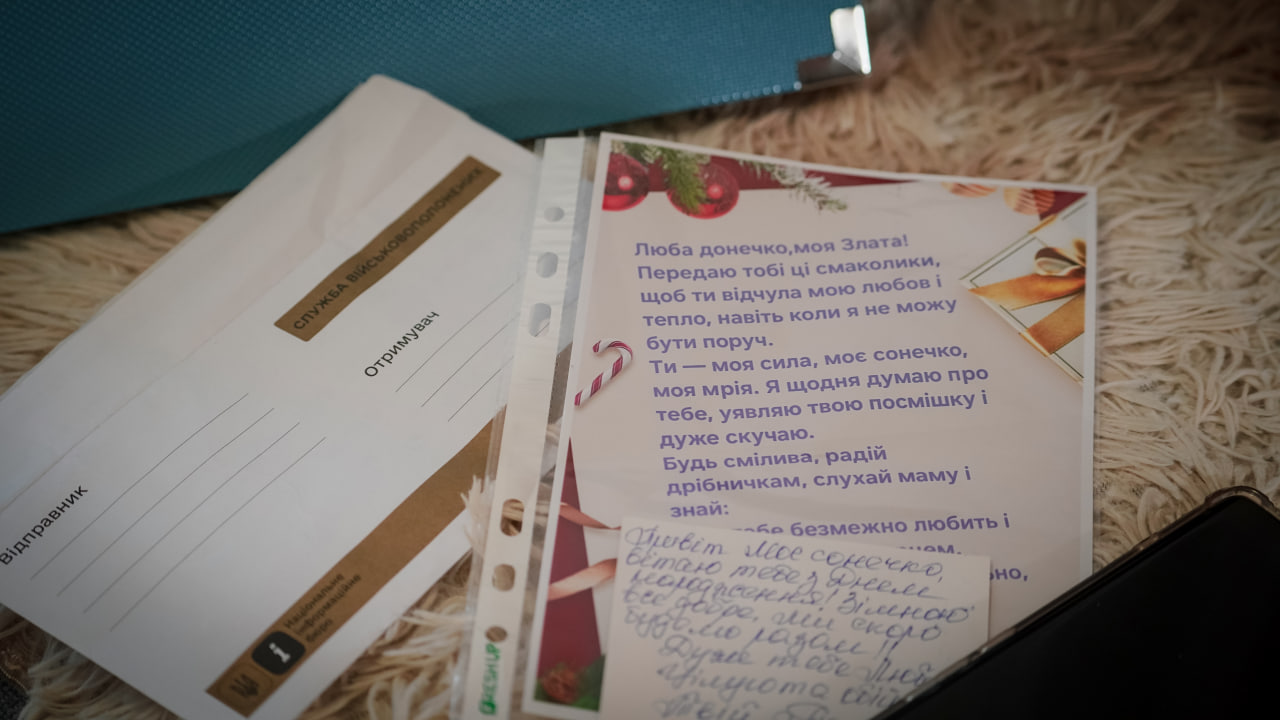

For athletes, this kind of support means a lot. Those of us outside sport don’t fully grasp what it means for them to be excluded from the Olympics.

A disqualification is the collapse of a dream they have worked toward all their lives. But the dreams of the people whose faces Vladyslav carried on his helmet have already been cut short forever — just like the dreams of their loved ones.

Vladyslav may still have a chance at the next Olympics. They will never have that chance. That is why this attempt to simply “erase” them from these Games in the name of regulations feels so deeply wrong.

A few weeks ago in Davos, security expert Carlo Masala and I discussed his widely talked about book If Russia Wins. It’s a dystopia in which even Estonia’s Narva ends up under occupation — the same city where you once symbolically relocated the presidential residence. We agreed then that Narva today is no longer the “Achilles’ heel” it once was. What have Estonians managed to achieve in this region? And in your view, what does a reliable deterrence system look like for a country like Estonia?

To be honest, Finland’s accession to NATO was the key deterrence factor for Narva. Before that, the city was a lonely outpost in the far northeast; now it sits on the shore of NATO’s “inner lake” — the Baltic Sea. This is a direct consequence of Putin’s actions: the security situation here has improved dramatically.

Another consequence is a profound shift in mindset. Even those who once felt nostalgic for the Soviet Union have changed their views under the influence of independent media and the obvious threat posed by the Russian regime. It’s a painful process. In Estonia there are many moving stories of people cutting ties with relatives somewhere beyond the Urals because they cannot reconcile themselves with what their “motherland” is doing.

So what’s happening? I think people’s outlook has become much clearer. It’s easier now to see where the real axis of evil lies in today’s world — Russia, China, North Korea. And this has become obvious even to our Russian-speaking population in Estonia.

I want to talk not only about defence, but also about the mental dimension of security. My acquaintance, Taiwanese journalist Jason Liu, who researches China’s influence, recently visited Narva. He was interested less in the “hardware” and more in the people — how the Russian-speaking part of society functions, the group Moscow tries to turn into a tool of influence.

I remember how, during your presidency, you symbolically moved the presidential office to Narva. It was a strong message: not “we won’t let you”, but “we are with you, we are here for you”. You fought isolation with presence and dialogue. But the world has changed. Russian propaganda and far-right movements now skilfully feed off people’s pain and sense of injustice, using general frustration to erode trust in institutions. How does Estonia counter this virulent strategy of anger? Is it even possible today to calm such societal resentment?

Estonia’s state model has been stronger than the Russian one since 1991. The only paradox lay in the status of so-called “grey passport” holders. Under pressure from our Western partners, we granted them visa-free travel both to the West and to the East. That turned the alien’s passport into one of the most coveted documents in the world: people clung to it for decades, even tried to pass it on to their children to avoid choosing a side. It was precisely this status that maintained a dangerous ambiguity about their loyalties.

The events of recent years changed everything. In 2014, a third of Russian-speaking Estonians openly said: “We are Ukrainians.” After 2020, another third identified themselves as Belarusians. The Kremlin’s aggressive actions pushed its own diaspora to rapidly distance itself from Russia.

We are now closing Russian-language schools for good. This should have been done much earlier, but international institutions — including the OSCE — did not fully grasp the risks.

And how is that perceived politically?

There is a certain irony here. What the grandmothers’ generation saw as a privilege, today’s youth sees as segregation. When I visited Narva, one main complaint kept coming up: young Russian-speaking parents want to send their children to Estonian schools. Because there are not enough places in the city, they have to move to Tartu or other towns to secure a good education for their kids.

Instead of fighting for “their own language” in schools, parents choose Estonian because they want a future for their children in a civilised European society. For them, it is the fastest path to integration. Against this very clear demand, we are left with one uncomfortable question: why did we postpone this decision for thirty years?

.jpg)

This is a telling case, and it reminds me of a colleague from a Moldovan village in Ukraine. Her mother deliberately chose a Ukrainian school over a Romanian one because it provided better education and broader opportunities. Ideally, every school should be strong regardless of the language of instruction. But the point is that today Estonian or Ukrainian are no longer perceived as something imposed. They are languages of opportunity that people want to master for the sake of their own future.

Exactly. My mother used to tell a funny story from the 1970s. Some Russian colleagues came back from a trip to Finland and were genuinely shocked that nobody there understood Russian. Soviet propaganda had convinced them for so long that it was the “language of international communication” that encountering reality became a real discovery.

In Narva, Russian is indeed dominant, but that doesn’t make all residents Russian. People from nineteen different communities live there — from Armenians to Chechens — and for many of them Russian is simply a lingua franca, not a marker of loyalty to Moscow. In the end we are aligning with European standards. There are millions of Russians living in Germany, but nobody is demanding state-funded Russian-language schools from Berlin.

In Estonia you can open a private school and teach in any language you like, as long as you’re not spreading the aggressor’s propaganda. But the state budget will no longer finance a system that kept people in ideological isolation. Estonia, like Germany or the UK, has no such obligation.

If we turn to defence, we are going through a critical moment: the world is increasingly debating NATO’s viability and the US role in the Alliance. NATO certainly exists — but is that enough? The accession of Finland and Sweden was a historic step. Still, have you seen any other tangible actions by NATO to strengthen Estonia’s security in recent years? Do you feel that your country is genuinely safer?

Obviously, yes. It all began in 2014 with the occupation of Crimea. Back then NATO’s resources were limited, and defence spending rarely reached 2% of GDP. In response, the Alliance introduced the so-called “tripwire” — a deterrent signal in the form of Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) in the Baltic states, as well as an enhanced presence on the southern flank in countries like Romania. That was essentially all NATO could do at that time.

Over ten years this initiative has grown into powerful brigades. Today French and British soldiers stand side by side with Estonians as one combined fighting force. We started almost from scratch: in 2017 the units didn’t even have common communications systems. Our allies learned how to fight on our terrain through their own mistakes: the British were learning territorial defence, and the French were discovering that Estonian bogs are no place for tanks. If Article 5 had had to be triggered instantly back then without preparation, the losses would have been catastrophic.

Today the situation is very different. Thanks to EFP and JEF forces, NATO’s eastern flank is much better protected. General Christopher Cavoli has drawn up a genuinely robust plan for building up NATO’s forces which, he says, will require 3.7% of our combined GDP.

What does worry me is something else: one day the war in Ukraine may end, or at least be frozen. Experience shows that whenever that happens, the pace of defence efforts tends to slow. But Europe is large enough that I’m confident NATO can continue to provide the necessary level of deterrence. I feel safer today than I did on 24 February 2022 — which, incidentally, is Estonia’s Independence Day. We were all celebrating then, but you can imagine what we felt that day. It didn’t feel like a holiday at all.

I must admit we, too, feel much more protected today than in 2022. But the question of how sustainable our defence is remains open. Recently, Professor Snyder and I had a meaningful conversation with the commander of Ukraine’s 7th Assault Corps, the 25th Brigade, which holds the Pokrovsk sector and is one of the country’s largest airborne brigades. Just that one corps is larger than the entire Lithuanian armed forces. It really highlights a fundamental problem for small NATO members.

Alliance standards require us to invest in very expensive systems — for example, aircraft — which in a large-scale attack will be among the first targets. The whole philosophy of NATO is built on interdependence and interoperability. It doesn’t really function autonomously. If allies do not come to your aid immediately, you are practically defenceless in the face of a superior enemy. How do you live with that? It feels like existing in a state of absolute dependence on your partners’ political will.

Today, when the foundations of NATO sometimes seem to shake under doubts and political noise, the key question sounds sharper than ever: will the allies actually fight when the first shot is fired?

NATO decisions are not made by some abstract “council” — each member state determines its own contribution. In Estonia this is set out in law: our units have the right to return fire immediately. If we are attacked, our troops will fight without waiting for formal decisions by parliament or the president. The French and British soldiers embedded in our brigades will act the same way.

That in itself sends a clear message: “We are here together — Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, whoever it may be. There is nothing to discuss. We have a plan, and we are ready to fight.”

We have not yet reached the 3.7% of GDP target, but political will is decisive. If the will is there — and we believe the presence of troops in our region shows that it is, for instance Germany is forming a brigade in Lithuania — then the means will follow.

Ukrainians had almost nothing, but they had will. NATO’s strategic thinking changed with the arrival of the forward presence forces. The military were the first to understand that they would be drawn into a fight from day one, which pushed them from abstract talk to real planning for reinforcements. Today NATO has “come out of the barracks”: constant exercises from Greenland to the Baltic have turned declarative deterrence into something practical.

Of course, the question of the “window of opportunity” for a declining empire like Russia remains. We have to be ready precisely for the moment when Moscow feels that window is closing. To avoid a catastrophic gap in readiness, we are building a system of collective deterrence without fear.

This morning I listened to General Hrynkevych at a breakfast hosted by the Atlantic Council and the Munich Security Conference. He put it very clearly: we need all our armies, and we need them to have asymmetric capabilities. States on the frontier, countries with strong submarine fleets or unique intelligence assets must all be part of one puzzle. His doctrine is simple: in a global world where crises can erupt simultaneously in the Baltics and around Taiwan, those who are not under attack at that moment must immediately use their resources to support those who are. That is the true essence of modern collective security.

General Hrynkevych is the commander of US Army Europe. What exactly did he say? We are hearing extremely mixed signals from the US administration. It often feels as if both the military and politicians are leaning toward stepping aside. I was at last year’s Munich Security Conference during JD Vance’s speech, but the situation has changed since then, and the mood in the White House has become even more ambivalent. So what was the tone of General Hrynkevych’s remarks — did he support that line or not?

If you strip away the political rhetoric, you see that NATO is moving forward because resources have finally appeared. Let’s be honest: for years the Americans urged us to increase defence spending, warning us about Taiwan and other global threats. The fact that they had to speak so bluntly is partly our fault.

Instead of endlessly dissecting mood shifts in the White House, we should focus on our own commitments. We must help Ukraine and be ready for any scenario. Even if we imagine an unlikely peace in which Ukraine maintains an 800,000-strong army — that will cost money. Just as our own deterrence system will. This challenge will not simply disappear.

We have to do our job regardless of what is being said in Washington — politely, harshly or not at all. It doesn’t matter. It’s time to take responsibility ourselves.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen recently said that her country has given Ukraine everything it could in terms of military aid. Now that their stockpiles are depleted, the focus is shifting to production: investing in Ukraine’s defence industry and boosting capacities in Denmark itself. Estonia is also extraordinary in this regard. It is hard to express how grateful we are to a country that has provided us with the largest amount of aid per capita.

But resources are finite. Where are you now? Have you begun rebuilding your own reserves? I know Estonian companies are already working with Ukraine in drone production. But where are you in the broader picture? You made the noble choice to give everything so we could hold on. Despite critics who asked why you were giving away your own weapons, I’m convinced this was the only right path.

We essentially outsourced our deterrence. It would have been unwise not to give what we had. The Danes understood this, as did all forward-looking allies. Naturally, we are replenishing our stocks: buying weapons around the world, restoring and upgrading equipment.

But modern war sets new rules. To effectively use “mass” from your depots, you first need to neutralise the enemy’s air defences, and in that niche the innovation cycle lasts just weeks. Accumulating huge piles of ready-made hardware today, for a war that might happen in five years, is absurd — the technology will be outdated by then.

We don’t need mountains of steel in warehouses. We need a mobile capacity to manufacture relevant weapons here and now. That means rethinking industry. Production facilities must be dual-use: today a workshop makes civilian equipment, and when needed it switches quickly to drones or missiles. There’s no sense in mass-producing drones for a hypothetical war years from now — by then they’ll be obsolete.

Ukraine’s experience has shown that the future belongs to flexible plants capable of producing whatever is required at that moment. That is the new strategic reality: keep only the necessary basic stock in storage, but build industrial muscle that allows you to generate “mass” on demand.

How popular is this policy in Estonia? From the outside we often see your position as monolithic and coherent. But a shift toward a defence-oriented economy and rapidly rising military spending almost inevitably provokes internal political debates. Is there a broad consensus in Estonian society on this course, or is it still a point of tension?

No, of course not. Russia is actively trying to fuel social media narratives that all social support money is being turned into tanks and missiles. But Estonians understand what is at stake.

The only complaint is that next year we will spend 5.4% of our GDP on defence while others are only slowly approaching 3%. I, however, don’t see that as a problem. Europe simply doesn’t yet have the capacity to absorb such volumes of money at once. If everyone suddenly started spending 3% tomorrow, it would only cause wild inflation in the defence sector and a chaotic shopping spree for equipment that doesn’t match real needs.

That’s why I fully support General Cavoli’s plan — and now General Hrynkevych’s — to build up NATO’s capabilities in a measured way, gradually increasing spending. For Estonians it’s a bit difficult: we are among the leaders in defence expenditure despite not being the richest or largest economy in the EU. But we are encouraged by the fact that we are not alone. There is the “Nordic-Baltic Eight” format — eight Nordic and Baltic countries following the same path. Together that’s 33 million people within the EU and NATO.

This is what Mark Carney calls a “middle power”. It’s the biggest ice floe we could climb onto as the ice breaks around us. And from his speech you can see that this group is already starting to play a role in the global conversation.

It feels like we are living in several parallel realities now. In Ukraine, they are different for the military and civilians. In the foreign press, however, everything tends to be reduced to talk of negotiations and deals. To me this path leads nowhere.

I agree. I haven’t met anyone who could explain to me why Putin would sign anything. What would be in it for him? There is no answer.

How do you see this situation? For instance, Carl Bildt asks bluntly: isn’t it time to drop this game of illusions? I’ve seen you at many events and I genuinely want to hear your take. Ukrainian officials, when dealing with Washington, have to be cautious: they show gratitude and try not to antagonise the US leadership in order to preserve the strategic relationship. That’s understandable and right. But because of that, they sometimes use a much harsher tone with European leaders, and to me that feels a bit unfair.

Is this attempt to “appease” the Americans worth it, especially given the pressure on Europeans? And isn’t it time for all of us to finally come back to reality?

I think we all understand that the current US administration can sometimes be unpredictable, so Kyiv’s daily efforts to maintain engagement with Washington are entirely justified.

The security guarantees being discussed between Ukraine and the US are crucial, although one question remains unresolved: why would Russia agree to sign anything? At the same time, it is essential to send a clear message to the Global South and the UN: it is Ukraine that shows readiness for dialogue, while Russia ignores talks and continues bombing.

What worries Europeans? The truth is that an experienced and powerful Ukrainian army is an enormous asset that NATO badly needs. It’s strange that this still isn’t widely recognised. Of course, the path to NATO and the EU will require serious work on the rule of law and legislation, but this integration is in everyone’s interest.

The worst scenario would be a dubious peace agreement, followed by elections whose results are manipulated by Russian propaganda. That could lead to an “anti-Maidan” and send Ukraine down the Georgian path. Europe cannot afford such a failure. That’s why we are trying to speed up Ukraine’s integration into Western structures — it’s a matter of our own security. And that is exactly what Ukrainians are trying to convey.

How serious do you think the current talk of Ukraine’s integration into the EU really is? Recently, at a dinner with American journalists and European analysts, I noticed a striking contrast.

The Americans were deeply sceptical: in their view, Europe will never go for it. They point to Ukraine’s internal political issues, the need for reforms, corruption risks, and treat the accession debate as empty rhetoric. The European experts at the table, meanwhile, insisted that in Brussels these discussions are very practical.

In this context, the idea of “soft integration” keeps coming up — a gradual entry into the single market and EU structures. How realistic is this scenario in the short term, say by 2027? Can this gradual approach become a genuine mechanism rather than just a way to postpone full membership indefinitely?

Georgia’s experience has shown that partial integration into separate programmes, without real political progress, leads to deep disillusionment in society. Europeans understand this. But we must be honest about one basic thing: the European Union is first and foremost an economic union. A political decision to accept a new member is not enough. Every European entrepreneur needs to be convinced that Ukraine is a safe part of the common market, where the legal system reliably protects investments and the rules of the game are clear and transparent.

This is a massive task, and Estonia had to do it as well. We too emerged from the Soviet Union with “scars” on our collective mindset — cynicism toward the authorities and distrust of laws. We had to change that mentality and convince people: “This is our rule of law, and it must apply equally to everyone.”

It was not easy. We even ran public campaigns like, “Don’t bribe the police — it delays our path to the European Union.”

So the first thing is honesty. In Estonia we chose radical steps. While other countries offered special benefits for foreign investors, we insisted on equal conditions for all. We were constantly faced with the question: are we “better” than Poland? Poland was a big, attractive market and its accession to the EU was never in doubt.

Today Ukraine is in a similar position. You need to do the same homework on reforming the legal system. But you have an important lever we didn’t have: Ukraine is a huge market, just as Poland was then. That’s your strategic advantage — but it doesn’t remove the obligation to create transparent rules, without which full integration into the Union is impossible.

I think a lot of this comes down to the scale at which you look at things. I want to talk about your security because it can give us hope. When discussing EU integration with businesspeople and journalists who specialise in economic issues, I often hear the argument: “No one will invest in the left bank of Ukraine — Kharkiv or Dnipro are too close to the Russian border.”

And I always say: “Wait, what about Narva? It’s even closer.” If you look at the Baltic states through the lens of scale, it becomes obvious that you can live and develop successfully right on Russia’s border, attracting capital and building an economy. Your security model proves that geographical proximity to the aggressor doesn’t have to be a death sentence for investment.

You make it sound as if Finland didn’t have the longest border with Russia of any NATO country… In fact, Finland has the longest land border with Russia in the Alliance.

Yes, but at least they have a big territory. In your case, it’s as if one small slice of the country is extremely close to Russia, and on top of that Estonia itself is small. If we truly think that proximity to Russia is a problem, then we have to conclude that nothing can be done in all these border regions. But Estonia clearly shows this isn’t true: life goes on, and it’s possible to build a prosperous state.

This is a challenge for all the Baltic states. Even Swedes and Finns spent years worrying about the safety of foreign direct investment. But that issue has been largely resolved through NATO’s strengthening. Today we are confident that the Alliance will defend every metre of our territory — and that confidence directly supports our investment climate.

Former Estonian Commander of Defence Forces General Herem once put it very well: a safe economic environment means having enough long-range missiles to stop the enemy at the border. That is the foundation of security.

I believe that once a just peace is achieved, investment will come to Ukraine as well. You have unique assets: from natural resources to a highly educated workforce. Estonia attracted capital without special incentives largely thanks to the education level of our society, and in this respect Ukrainians are very similar to us.

The history of EU enlargement shows different approaches to labour markets. The UK and Ireland immediately opened their borders, which later helped push Britain toward Brexit. Germany and France kept their borders closed, so capital moved in the opposite direction — instead of people going west, factories were built in Eastern Europe. That stimulated our economies.

European welfare systems have many flaws, but everyone is reaching the same conclusion now: strategically, it is more beneficial to have production nearby than to move it to somewhere like Vietnam. In that sense, Ukraine is a unique opportunity for all of Europe.

You once ran a power plant. I’m asking about this because energy used to seem like a dull sector but now it’s absolutely central.

I ran a Soviet-built power plant with a capacity of 110 and 90 megawatts — it supplied heat to all of Tallinn.

Given that experience, how do you view Russia’s attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure today?

In Estonia we are taking a different approach, although if everything depended on me, I would push for maximum autonomy. We have to admit that Europe does not have significant fossil fuel reserves of its own. So the only path to true energy independence is “green” generation.

Obviously, an instant transition is impossible. Gas will be needed as a transitional fuel to cover peak loads. But the future belongs to a clean energy system based on wind, nuclear power and pumped-storage hydropower.

Nuclear energy involves two different approaches. On the one hand, having a nuclear plant brings in the IAEA as a security guarantor willing to talk to anyone to prevent shelling of nuclear facilities. On the other hand, large plants are extremely vulnerable. Until small modular reactors become commonplace, we are trying to manage without big nuclear stations, especially given the existing capacities in Finland and Sweden.

Our priority is decentralised generation: wind, solar, gas and energy storage. As Ukrainian experts rightly say, you shouldn’t build facilities larger than 50 MW. A decentralised system of generation and distribution is much more resilient from a security standpoint. If I were the “tsar” of Estonia, that’s the direction I would take.

Today I had the chance to listen to the CEO of DTEK — he also stressed the importance of decentralisation. But I’m interested in what you feel when you see footage of destroyed power plants. Unlike most civilians, who just see damaged buildings, you understand exactly how these systems work. You know where the strikes are aimed and which components are critical.

Based on your experience running a power plant, how would you explain to Americans or Europeans what Russia is doing to Ukraine’s energy system? What do you see where others see only ruins?

First of all, it’s crucial to understand the role of district heating. It is essentially a strategic resource that allows you to use fuel as efficiently as possible. In a classic old-type power plant, the usual ratio is 100 MW of electricity to 200 MW of heat.

Without a connection to a heating network, that heat potential is simply lost, and the plant’s efficiency will not exceed 40%. If you use the heat for city heating, efficiency rises to 90–95%, even at old Soviet facilities.

What Russia is doing now is a deliberate destruction of Ukraine’s energy efficiency. Power systems across the former Soviet space were designed on the principle of cogeneration, which makes combined heat and power plants twice as efficient as conventional condensing plants. By destroying these facilities, Russia is hitting not only electricity generation but also district heating systems.

Rebuilding such networks is extremely expensive and time-consuming. As a result, people are forced to turn to primitive solutions — wood stoves, gas boilers, generators. The aggressor is not just disrupting comfort for one winter. It is destroying critical infrastructure that is the foundation of Ukraine’s energy-efficient future.

Is it actually possible to prove that this type of strike is a war crime? How do you see it in the context of international humanitarian law?

We are already witnessing numerous war crimes by Russia: deportation of children, killings, torture, rape, hostage-taking. Frankly, those responsible for this war should have ended up in The Hague ten times over by now. Will one more life sentence on their record change anything? Hard to say.

But the destruction of energy infrastructure is definitely a war crime, because it destroys the conditions needed for life and makes the land uninhabitable.

And how do you protect against that?

International legal mechanisms have shown themselves to be, let’s say, weak. So the only real way to protect yourself today is decentralisation: shifting to small facilities and building them underground.

As for justice, major conflicts usually push international law to evolve, but this time the process is painfully slow. At first there was hope for a universal tribunal, but when that failed, European countries began acting individually. It seems that for now the prevailing logic is: first we have to solve basic survival problems, and only then can we turn to justice.

I’d like to briefly return to Estonia. I visited in the first year after the full-scale invasion and was struck by how warmly people welcomed Ukrainians and how quickly new Ukrainian schools appeared. But even then it was clear that, per capita, the number of refugees you took in was extremely high.

For Tallinn, 30,000 new residents is an enormous strain that immediately exhausted the rental market. Small countries have a natural limit to how many people they can absorb before frustration appears. Is that dynamic visible now in Estonia? Are there voices saying that there’s no more room and the inflow is too large?

Interestingly, no. We have no problem with the number of people, but there is a key condition: integration into Estonian-language society. A nation of one million has a constitutional obligation to protect its language and culture.

So all Ukrainian refugees who learn Estonian and can speak it are very welcome and can stay for generations if they choose. We place great emphasis on language as the core of national identity. It doesn’t matter whether your name is Oleg or something else — if you speak Estonian, you are one of us.

A vivid example is politician Jevgeni Ossinovski, who has Russian roots. People see him as Estonian, despite his background and his own ironic references to being an “integrated Russian”.

If, after ten years here, you still speak only Russian, we will inevitably begin to distrust you. We cannot move forward with those who cling to Soviet nostalgia, believe in Russia’s “natural superiority” or display Russian chauvinism by refusing to learn our language.

Estonia will not adapt to such views. We went through depopulation in the 1990s and the decline of Soviet industrial towns, so we do in fact have room for new people — for example in Kohtla-Järve. But trust is built through language.

My guidebook “How to Become Estonian” is simple: learn our language, use it, show a desire to be part of our culture. At home you can cook Ukrainian food, celebrate your holidays and speak your own language, but social integration in Estonia only happens through Estonian. That’s how you earn our full trust.

You were often the first woman in strategically important roles, from running a power plant to becoming president. Do you think there is still a glass ceiling for women at your level?

Obviously there is. Even when you break through it, your authority is constantly questioned. I’ve had the same answer to comments about my gender for more than twenty years now.

When I’m under pressure and someone says, “You understand, we simply have to ask — you’re a woman in such a position…”, I reply: “What exactly do you need a penis for to run a power plant?” Neither I nor the men asking this question have an answer.

Doubt follows you everywhere: your wardrobe, the way you stand, the way you speak. If you are decisive, you are labelled too harsh and people are afraid of you. If you show flexibility, they say women are too soft for such roles.

When I raise the topic of domestic violence in Estonia, explaining that it is a root cause of social tension and low birth rates, people tell me: “You care about this only because you’re a woman.” They don’t see systemic analysis — just “female empathy”.

There is definitely a glass ceiling in Estonia. That’s why we women need to support one another.

Once I helped a female politician from a party I would never vote for. She was in despair: “I haven’t even started the job, and journalists are already convinced I’ll fail. Why?”

I told her: “Look at yourself. You’re forty, attractive, successful and going for a high-paying EU post. They are trying to belittle you simply because in their minds a woman has no right to that level of success.”

It can be hard for some men to accept this. Not for all, and not in every generation, but it is noticeable. Some even sincerely pity my husband — as if he’s a “poor man” who has to make pancakes on Sunday mornings. So what if he does?

What advice would you give based on your experience?

My advice is to speak up. Never stay silent. When Kaja Kallas won the elections, people asked me, for instance: “What will it be like to have two women leading the country?”

I had a counter-question: “Did anyone ever ask my predecessor, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, what it would be like to have two men leading the country?”

Thank you.