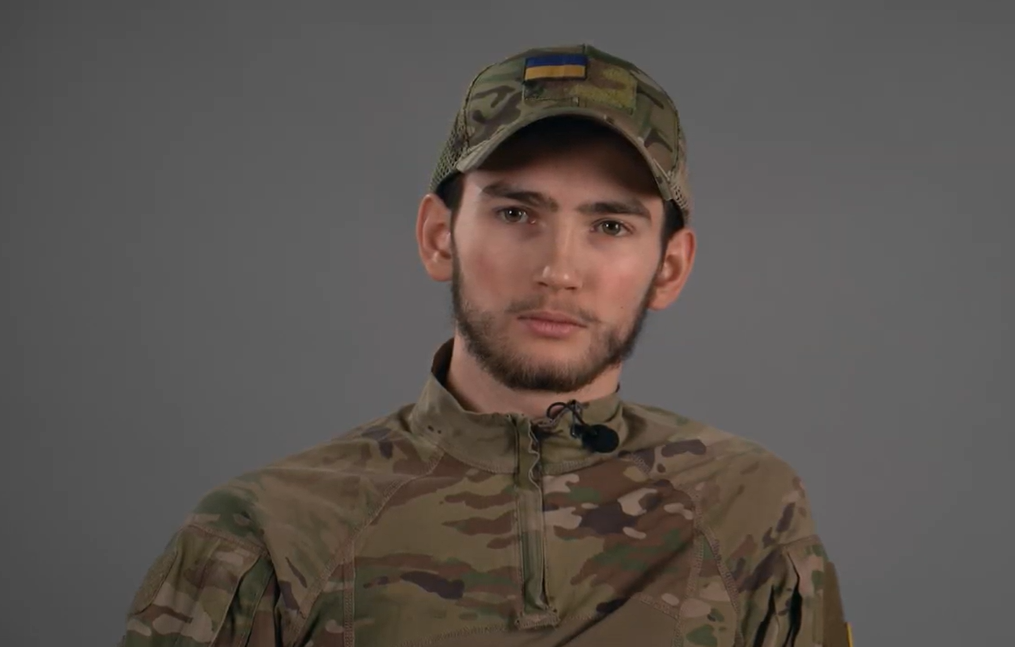

“China is doing everything it can to make people in Taiwan stop believing in democracy,” Jason Liu

Taiwanese journalist Jason Liu was born in 1987 — the same year martial law was lifted on the island after thirty-eight years. This period in Taiwan’s history is also known as the “White Terror,” remembered for widespread repression, the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, and severe restrictions on civil rights and freedoms. Since then, the island has been building a democratic state. However, Liu reminds us that the people of Taiwan have been fighting for their rights since the late 19th century, after the island was colonized by Japan. Today, Taiwan is under immense pressure from neighboring China. The PRC uses armies of bots on social media, various influence agents, political parties, and media outlets to shape public opinion and create chaos within the country’s democratic system. For example, the national parliament is now dominated by the pro-China Kuomintang party. It promises a “new era of peace,” cuts budget spending on weapons procurement, and reduces investment in the island’s civil defense system. Meanwhile, China cooperates with Russia and studies its lessons from the war in Ukraine with one goal — to better prepare for a future invasion of Taiwan.

Journalist Nataliya Gumenyuk in our podcast “When everything matters” speaks with Jason Liu about Taiwan’s preparations for a possible Chinese invasion, the country’s relations with the new U.S. administration, how Taiwan’s advanced high-tech industry can be used for defense — and how Ukraine might take part in this — as well as how the island understands the legacy of a century-long struggle for its rights.

Jason, I’ve been looking for an opportunity to have this conversation — to talk about your work in Ukraine and Taiwan. But first, tell me: where are you now? I know you're in Estonia. Why there?

Yes, I’m in Estonia now. I came here to see how one of the most advanced digital democracies responds to hybrid warfare from authoritarian regimes. I’ve been speaking with government officials and local residents — it helps me feel the general mood. I just returned from Narva, a city on the border with russia.

What did you see and hear there? What conclusions did you draw? In Narva, the Russian threat feels almost tangible.

The atmosphere felt familiar, even though I’m here for the first time. Estonians were very welcoming: they gave me a tour so I could better understand the city’s story and feel its context. And I can say this — Taiwan and Narva share a lot. Both places have people with different identities and languages, and next door is an authoritarian regime that tries to distract from real social needs. The difference is that Estonia has NATO and the EU — Taiwan does not. But the challenges look remarkably similar.

You’re very solutions-oriented. What is the key lesson from this trip across Europe that could be useful for other democracies?

The biggest lesson is seeing how small democracies like Estonia or Taiwan fight for their subjectivity. It’s easy to unintentionally create division: if you emphasize cultural and linguistic uniqueness too strongly, you risk distancing part of society from political life. That opens the door to external influence. For small democracies, this is a central dilemma — how to build national identity that includes everyone, not just the majority. This is exactly the lesson I want our politicians in Taiwan to understand: how to defend ourselves while taking care of all our people, how not to allow internal fractures that could become vulnerabilities during hybrid warfare.

We learned this the hard way after 2014. But tell me more about Taiwan. Why is part of society leaning pro-China? Why isn’t there full unity in the face of the threat?

Many people don’t understand why the Kuomintang — a party that once fought communists — is now seen as pro-China. It’s a long story, but here’s the core. Our state’s official name is still the Republic of China. It once held the “China seat” in the UN until the US shifted diplomatic recognition to the PRC. After losing the civil war, the ROC government retreated to Taiwan and imposed martial law for 38 years — without freedom of speech or basic rights. This was the period of the “White Terror.” I was born the year it ended — 1987. Since then, Taiwan has been building democracy. The Kuomintang gradually lost support, especially after the 2014 Sunflower Movement protests against deeper economic integration with China. But after eight years of rule, the Democratic Progressive Party also made mistakes, and some people began looking for alternatives. The Kuomintang, with support and media influence from the mainland, mobilized voters and now controls the parliament. This affects the budget — defense and civil preparedness initiatives get blocked. At the same time, social media became extremely influential. During the last internal Kuomintang leadership elections, even party members said that bots from the mainland helped secure the victory for the new leader. So now, the party’s chairwoman is someone openly supported by Beijing. This is the reality we’re dealing with.

It’s a new type of crisis — when the public discourse itself shifts because of external interference. Let’s return to democracy. In Taiwan, democracy is seen not only as a political system, but as a mechanism for protecting identity. Can you explain that?

There is a four-volume study about a century of democratic struggle in Taiwan. It shows how local people fought for rights starting from 1897, when Japan colonized the island. Later, they fought against the authoritarian ROC government, which imposed martial law and destroyed generations of elites. This experience is deeply rooted in our collective memory. We know stories of people who secretly printed magazines, studied human rights, and connected with international communities despite repression. It was democracy practiced under pressure. Today, we continue that struggle — only now the pressure comes from the PRC. The difference is that today we have a tool: democracy. We vote, organize civic initiatives, donate to independent institutions. This is how modern Taiwanese identity is formed — not through ethnicity or language, but through democratic practice. We speak Chinese; we share elements with China, but we also have Japanese and American influences. Our foundation is civic identity, not ethnic identity. China tries to undermine this through social media, influence agents, politicians, media. Our mission is to keep imagining and practicing democracy. For more than a hundred years, previous generations did this. Now it’s our turn.

Your line — that the very existence of a Chinese-speaking democratic community proves democracy is possible in a Chinese-language environment — is brilliant. And your metaphor: “If russia is an earthquake, China is climate change.” But sometimes it feels like a typhoon now. Where is Taiwan in this global dynamic?

Recently, I was in Finland and Sweden. Everywhere I heard the same thing: we are not alone. Many societies see the world now as a clash between two systems — democratic and non-democratic. The war in Ukraine made this obvious. And I was struck by how closely China and russia cooperate — and how hard it is for democracies to coordinate with similar efficiency. If authoritarian regimes can unite so effectively for invasion, why can’t democracies unite just as effectively for defense? This is the core question today.

How are you preparing? If the leading party blocks defense budgets and calls preparedness a “provocation,” how can society be ready? We also didn’t believe a full-scale war was possible until 24 February.

There is no honest, definitive answer. For years, any mention of a possible attack was labeled “provocation.” But recently, the government released a civil defense manual — basic emergency instructions. This alone shows how difficult it is to speak openly even about obvious things. Today, we do everything we can. The president created a National Security Council that includes analysts, academics, the private sector, government officials, and the military. We meet quarterly to discuss different threats and approaches. Civil society is very active: young people organize drills, new civil defense groups appear, people teach courses, record podcasts, hold events. The problem is that parliament is cutting budgets at the same time, and information attacks target anyone discussing readiness. Working in such conditions is hard. But there is progress. In Finland and Sweden, I learned that our officials are studying their resilience models. That means the government is slowly changing. International support is crucial for us to prepare properly.

Another feature of Taiwan is its strong economy. How can high-tech industries, especially semiconductors, help in a potential war with China?

Economy is our way to survive. From childhood we’re taught that Taiwan feels safe only because the world sees us as a crucial technological hub. We aren’t members of most international institutions; with a Taiwanese passport you can’t even enter the UN building. So our global presence depends on what we produce — our technologies and knowledge. But turning this potential into a defense industry — that part is still ahead. We lost time because previous governments avoided developing defense tech in pursuit of “peace” with China. Now we see how important it is to learn from Ukraine, which innovates directly on the battlefield. The idea of joint innovation or venture funds — combining Taiwanese tech and manufacturing with Ukrainian engineering creativity — has huge potential. It could create a new defense ecosystem for democratic countries. You have engineering genius. We have money, technology, and production. It’s a natural match. But we’ll have to build such partnerships through alternative channels, because we aren’t members of international institutions.

Let’s return to China. How would you honestly assess the level of Chinese defense technology?

Just as we invested our talent into semiconductors, China invested everything — people, money, institutions — into defense technologies. They publish analytical reports showing how they study russia’s war against Ukraine, copy weapon designs, adapt production, and prepare for potential invasion of Taiwan. They analyze the battlefield, test technologies, then mass-produce more — and all of this is documented. Their progress relies heavily on cheap labor and a government that doesn’t care about the well-being of citizens. Meanwhile, youth dissatisfaction, unemployment, and local protests are growing — but the outside world rarely sees this because of censorship. It’s important to distinguish the regime from the people. PRC citizens are monitored, even abroad. Their voices are almost never heard. It resembles the Soviet era. And the key challenge is: how do we have honest conversations with ordinary Chinese people?

Another important topic is the new US administration. Can Taiwan rely on automatic US intervention if China attacks? What is your sense of Taiwan–US relations after Donald Trump’s victory?

I can’t speak for our government or reveal details of negotiations. But here’s what I can say: we follow the situation daily. Everything can change after a single post or statement. Public messages don’t always reflect real processes. We act with maximum restraint. We do everything we can to defend our values: finding allies, developing technology, strengthening our economy, building civic diplomacy, forming partnerships — including with Ukraine.

There’s a large clash of systems happening now, and it’s crucial for the US to see Taiwan as part of its strategic vision.

A year has passed since Trump took office. Ukraine experienced a difficult period in relations with the US — but we still held our diplomatic line.

Yes, there are no perfect answers. Only trying to find solutions within the circumstances we have.

What do you think about the recent meeting between the US president and China’s leader?

I don’t see anything fundamentally new. Their interests are clear. The confrontation continues. The positive part is China’s announcement of establishing a direct communication line to prevent accidental escalation. They want to avoid direct confrontation. For us, this matters: almost nothing on the mainland is transparent, including military movements. Any reliable channel reduces risk.

Congratulations on your nominations for journalistic awards in Taiwan for your Ukraine reports. You once said that Ukraine’s ability to turn crisis into opportunity was your main insight. What other lessons did you take from Ukraine?

Our spring report from Ukraine was nominated for two major awards; our YouTube video was nominated as one of the most influential of the year. We achieved this thanks to support from civil society. In Ukraine, I saw that crises are inevitable — but people use them to build something better. I hope Taiwan learns this too. We need guidance: how to use windows of opportunity, how to avoid political infighting, how to build something new — democratic, inclusive, secure. Not all Taiwanese appreciate the democracy they have. Some feel pessimistic about the future. A small part even wants to join China — to be part of a “great power.” It’s a minority, but it exists. We must learn to value what we have and use crises to build a better future. That’s why I want to learn from Ukrainians — how you do this.

Taiwan is a highly technological society. But you often say that offline events matter. Why, when social media reach thousands?

Social media succeed because people seek community and identity. But online connections are fragile. Real human contact is becoming more valuable. Almost every week I host offline events — about Ukraine, disinformation, or simply moderating conversations in local communities. These meetings build a real community that supports one another. It’s essential for civil society, journalists, anyone working with people.

Experts often say offline engagement is too small-scale compared to algorithms. Why does it still matter?

Numbers can be misleading. You see ten thousand views and think: “Why hold an event for fifty people?” But if you do it for years, you see something different: one conversation can change a person so much that they become active, motivate their family, join public life. They then support your work. Offline creates decentralized networks. Each person becomes a center for their own community. In my city, we had a café where we hosted weekly events. Sometimes a hundred people came. They would hear Hongkongers speak, ask questions, see real faces. Media alone could never create that. Offline and online approaches don’t contradict each other — both matter. But offline brings real relationships. And when I write stories, I remember the faces of those people. It gives meaning and motivation.