The world is inventing new ways to attack journalists. Can they be protected?

As of early December 2025, 124 journalists have been killed worldwide, and 377 are imprisoned. These figures were published by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). The number of journalists killed has already matched last year’s total, which was considered a record. More than 50 of them were killed during the war in Gaza. According to CPJ Executive Director Jodie Ginsberg, Israel has in recent years deliberately tried to portray journalists as terrorists or terrorist sympathizers in order to undermine trust in them. This creates an environment in which killing journalists no longer requires justification. The trend of labeling journalists as a security threat can also be seen in other countries. “If journalists are branded as a threat simply for trying to gather facts and inform the public, it becomes much easier to justify restricting their work,” Ginsberg says. At the same time, she notes some positive changes in coverage of the war in Gaza: journalists have begun to stop treating Israel’s official position as the ultimate truth, are asking difficult questions, verifying facts, and trying to understand what is actually happening. However, the way this conflict was covered earlier will have consequences for journalism for decades.

In the podcast When Everything Matters, journalist Nataliya Gumenyuk speaks with Jodie Ginsberg about the “normalization” of killing journalists, the state of American journalism under President Trump, whether employees of propaganda outlets can be protected, and how laws are used to pressure media workers.

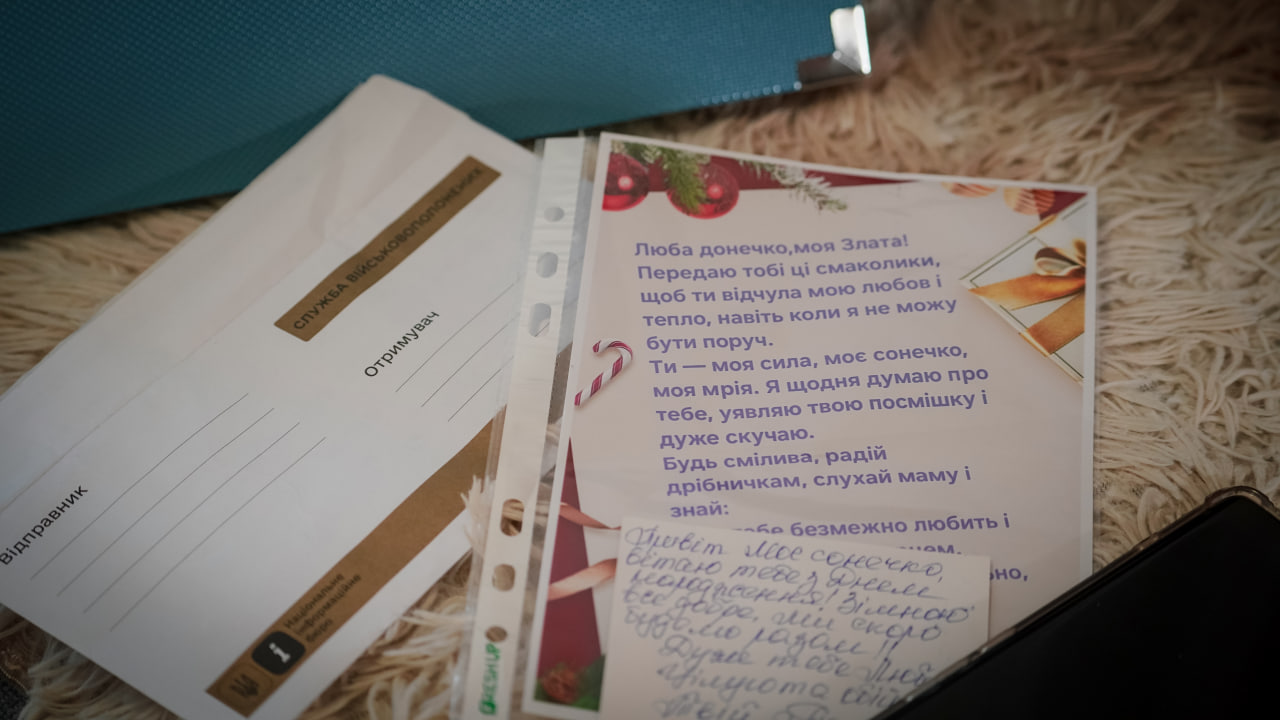

Jodie, this conversation is important to me because we are increasingly seeing that journalism as a profession no longer has the protection society once seemed to guarantee. On the contrary, during war or any other crisis, journalists are more and more often turned into targets. Around the world, journalists are attacked by armed groups and governments — and this happens not only in authoritarian states, but also in democratic ones. My first question is about Ukraine: around thirty of our colleagues are still being held in Russian captivity. I understand that organizations like CPJ can do very little when a journalist is killed by shelling on the front line. That is a horrific but at least visible, physical threat. But when a journalist is imprisoned, a different question arises: is there any leverage at all that can help bring them home? This is especially painful to talk about because of our colleague Viktoriia Roshchyna. Her case was raised at every level, discussed by international organizations, including CPJ — while she was still alive. And yet Viktoriia died. She did not survive imprisonment. We still do not know exactly what happened to her. There are reasons to believe it was not only about inhumane conditions, but also torture: she was abused, beaten, and it seems she was never meant to be released. We waited a long time for her body to be returned. This experience leaves a sense of complete helplessness. What can organizations like yours do to at least preserve the lives of those who are still alive?

Stories like Viktoriia’s are heartbreaking precisely because we know that sometimes we simply cannot get someone out of prison when we are dealing with a regime that does not respond to any pressure from international organizations. Unfortunately, the number of such regimes is growing. By bringing cases into the public eye, however, we at least signal to the authorities that they are being watched. Our constant hope is that even if this does not lead to release, it might provide some degree of protection and make them treat the person more cautiously. That is why Viktoriia’s death was so shocking: it seemed that after the attention of the international community, at least some safeguard should have worked. What happened has forced us to reassess our approaches. At CPJ, we used to conduct an annual prison census, documenting journalists behind bars. But this method quickly became outdated: people were detained, transferred, disappeared without explanation. The situation changed daily. So we shifted to more dynamic monitoring that allows us to respond almost in real time. We also changed how we approach imprisonment itself. It is not enough to know how many journalists are in prison — it is crucial to understand the conditions, the treatment, the daily experience. In many countries, political prisoners are deliberately sent as far from home as possible as part of a strategy of isolation. We therefore look for ways to provide at least minimal support and to involve more people whose presence sends a clear signal: this case is being watched. One example is the case of Filipino journalist Frenchie Mae Cumpio. We tried to tell her story in a way that would encourage international observers to get involved — for diplomats to attend court hearings and visit her in prison. This raises the political cost for the authorities. Many regimes, including Russia’s, can easily ignore CPJ as a US-based organization. But it is much harder to ignore foreign diplomats sitting in a courtroom. This is one way to increase pressure even when we cannot directly secure someone’s release. At the same time, we began looking more closely at the moments when imprisoned journalists are most vulnerable. One of these is during transfers between facilities, when people can suddenly disappear and no information is available about where they are or what is happening to them. Our task is not only to document these moments, but to quickly alert those who may be able to influence conditions: we are watching.

This brings us to another terrifying phenomenon — the “normalization” of killing, when the violent death of a journalist stops shocking people. Even I, someone who closely follows international news, reads about the war in Gaza, and signs most letters in support of journalists worldwide, missed one of the bloodiest attacks in decades. During an Israeli strike on Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, 31 journalists were killed — the largest mass killing of journalists in decades. I only saw this news on the CPJ website. Someone like me can simply miss it in the news.

But you understand why this is happening. In recent years, Israel — and not only Israel — has deliberately tried to portray journalists as accomplices of terrorists, as unreliable and untrustworthy people whose work should not be believed. Commenting on its attack in Yemen, the Israeli army claimed that the journalists were part of a propaganda wing of military structures and that their killing was therefore justified. We hear such explanations again and again when it comes to the war and genocide in Gaza. This is how killings are being justified today. The reaction to the mass killing of journalists in Gaza has been extremely muted. That is why you did not hear about this case. Israel has managed to impose a narrative that every journalist in Gaza is suspicious, not really a journalist, and not fully deserving of protection. This plants doubt. People begin to think: maybe that’s true? Maybe they are not really journalists? Maybe it is not that important. What is characteristic of Israel is that this was happening even before October 7. There were many cases when Israeli forces killed a journalist and then, with little evidence, labeled them a terrorist. During the genocide, this mechanism only intensified. The pattern is simple and repetitive: a journalist is killed, Israel calls them a terrorist, presents unconvincing “evidence,” and moves on as if the issue is closed. After October 7, we saw an even worse trend — statements made in advance, effectively preparing justification for future killings. This happened, for example, in the case of Anas al-Sharif, an Al Jazeera journalist killed in August 2025. For more than a year, we observed campaigns to discredit him. The accusations constantly shifted and escalated as the war progressed. Two weeks before his death, we warned that he was being “prepared” as a target. Unfortunately, that is exactly what happened. And he was not the only one killed — several other Al Jazeera journalists died alongside him. Israel did not even attempt to explain their deaths. This creates an environment where, at a certain point, no justification is needed at all to kill journalists, because their killing becomes normalized.

We know that according to CPJ data, 249 journalists have been killed in Palestine, 166 injured, and 94 are imprisoned. But I want to return to the case of Anas al-Sharif. I have to say, it hit me especially hard. I learned about his killing just days after the funeral of Viktoriia Roshchyna. I saw that many Ukrainian media outlets almost verbatim repeated the IDF press release about the “elimination of a journalist linked to Hamas.” But if you simply Google Anas’s name, the first thing you see is a CPJ warning about a discreditation campaign. There is also a call by a UN special rapporteur to protect him because he was under threat. This is so easy to verify — one search query is enough to see a huge red flag saying: stop, he is being targeted, he is being prepared for accusations. And yet he was still killed. In your view, has the situation shifted at least slightly? Are leading media outlets trying to dig deeper into what is really happening to journalism and journalists in Gaza? Or does CPJ still have to almost single-handedly break through the established narrative of “unreliable journalists” in Gaza?

After October 7, something did change, although not fundamentally. We overcame the moment when the broader information space almost entirely reproduced Israel’s position as the ultimate truth. Journalists began doing their job: asking difficult questions, checking facts, trying to understand what is actually happening. Our task as journalists is to remain skeptical and cross-check information. But when it comes to Israel, we repeatedly see many people willing to accept the Israeli version above all others, without questioning it. Very often, what Israel or its spokespeople say is what ends up in headlines. Yes, the situation has somewhat improved. But we are still facing an extremely powerful narrative aimed at undermining trust in journalists working in Gaza. In terms of numbers, according to our data, 206 Palestinian journalists have been killed in Gaza as a result of Israeli actions. There are also Yemeni journalists killed, several Lebanese journalists killed in Lebanon, and three Iranian journalists killed. Overall, this remains a very difficult information battleground. I believe the way media covered Gaza will have consequences for our profession for decades.

In what way? Are we talking about trust in leading media because of how they covered the war in Gaza?

First and foremost, this is about trust in journalism as such. Many people feel that media outlets took sides instead of doing their job and honestly reporting the facts. There is also a hierarchy at play — the assumption that Western coverage is somehow superior, more ethical, more morally grounded. I have spoken to colleagues from the Middle East who said they once looked up to major international outlets, invited their editors to run trainings, to share standards of ethical journalism. But after those outlets failed even at the most basic journalistic tasks and could not cover Gaza honestly, trust was lost to such an extent that returning to that kind of cooperation no longer makes sense to them. These consequences should not be underestimated. They will first affect journalists in the region, but they will also undermine overall trust in Western media.

Is it easy for CPJ and other US-based organizations to take such a clear position as yours and call genocide genocide? After all, there are donors, there are risks. I’m not necessarily talking about self-censorship, but about pressure — including the fear of losing funding. I remember that after October 7 many organizations were forced to make a choice about how exactly to talk about what was happening.

When it comes to terms like “genocide,” maximum clarity is required. This is one of those topics that very quickly turns into a debate about who has the authority to make such determinations and based on which criteria. Our organization’s role is not to independently classify events as genocide. There are specialized institutions and human rights organizations whose mandate it is to make such legal assessments. We rely on their research and then determine how to speak about events based on that work. That said, the pressure was enormous, especially in the United States. I did hear accusations like: “Why are you paying so much attention to Gaza? Are these people even journalists?” This is something I have never had to hear in relation to Ukraine. Or: “Why does CPJ publish statements about Gaza every week?” — as if we were somehow exceeding our mandate. We were simply doing our job. I also know that other organizations hesitated to speak about Gaza for various reasons. We spoke out not because of a political position or personal interest, but because documenting threats to journalists and publicly reporting them is exactly what we exist to do. We did the same thing we have done in Ukraine, Afghanistan, and elsewhere: documented attacks on journalists. What we recorded became the deadliest period for journalists in the history of our monitoring — and those killings were carried out by Israel. Of course, there can be debates about how documentation is done or how we define who qualifies as a journalist. But one thing we cannot be accused of is inconsistency. We applied the same approach we use everywhere else.

When you talk about defining who is a journalist, I’m reminded of a conversation with Mexican journalist Alejandra Ibarra, who is building an archive of journalists killed in Mexico. She said that a large proportion of those killed are local — even hyperlocal — journalists. These are not always stories about cartels or major organized crime. Often it’s a reporter from a small town who wrote critically about local authorities. The threat often didn’t come from some abstract structure, but from very specific officials with ties to criminal groups. Alejandra also acknowledged that some of these people worked more like bloggers: their writing was emotional, uneven, subjective. And yet, when a journalist is killed, everyone suddenly starts talking about their “impeccable” work. This matters to me because I think about Ukrainian journalists who were killed or persecuted. Among them, too, were not “perfect” authors — sometimes with emotional, almost blog-like styles. But this can never justify killing or pressure. What interests me is how easily the focus shifts to the “quality” of their work, as if that determines whether a person deserves protection. And this isn’t only about extreme cases. Very often the targets are those who simply don’t fit the conditional Reuters or BBC standard, but who still honestly do their work as best they can, in the way they know how.

This is a constant question for CPJ. We define a journalist as someone who regularly gathers and disseminates factual news. Unlike deliberate, systematic disinformation, emotionality itself is not a problem. There are cases where a person has journalistic experience, but we do not include them in our list of imprisoned journalists if their arrest is unrelated to their journalistic work. In many countries, the line between journalism and activism is blurred. The mere fact of independent reporting already becomes an act of resistance, and reporting itself is sometimes the only way to draw attention to an issue. Environmental journalism is a good example — it often overlaps with activism. So we ask a simple question: is journalism the person’s primary and regular activity? If you took a photo at a protest but work as a taxi driver in everyday life, that does not make you a journalist. Although, of course, that still does not give anyone the right to persecute you for expressing yourself.

You mentioned people who systematically lie — and this is where the line becomes especially blurred. We know for a fact that Russia Today is propaganda. There is no debate about that anymore. It carries out a state task: spreading disinformation, hate speech, and sometimes even direct calls to violence. How should we treat such state structures in authoritarian countries that outwardly look like “almost media” but are in fact tools of power? How do you work in such a complex information environment, where independent journalists exist alongside entire state propaganda machines disguised as media outlets?

There are no simple answers here. In each case, we try to look very carefully at what a specific person actually does. Even if a media outlet as a whole functions as a state mouthpiece, roles within it can differ greatly. Sometimes people working there genuinely provide their communities with important, verified information. So we do not judge by the institution alone, but by the journalist and their work. A good example is Chinese journalist Dong Yuyu, a recipient of our International Press Freedom Award. He worked for the state-run Guangming Daily, but was arrested simply for having lunch with a Japanese diplomat in Beijing. He was later accused of espionage. If we followed a principle of “we do not support anyone working for state media,” we would have ignored his case entirely. But for us, what matters is the journalism he did and why he became a target.и I remember one event where a European minister said, “Look at how terrible the media are — all Murdoch outlets, for example.” That kind of framing deeply concerns me. When you label all media as the same, you stop seeing the people inside — those who are actually doing honest, important work. That is why we always try to assess the individual journalist, their reporting, and their impact, not just the organization they work for.

You recently wrote a column for The Guardian about how Donald Trump effectively trivialized the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. He was brutally killed inside the Saudi consulate, and Trump reacted with something like, “These things happen.” It reminded me of Vladimir Putin’s reaction to the sinking of the Kursk submarine, when he was asked about the fate of the crew and simply said, “It sank” — the same coldness, the same indifference. This brings me to a broader question about the state of American journalism. How serious do you see the threat to independent media today? Does American society have enough solidarity and readiness to defend newsrooms that are being pushed to the margins or pressured into silence? Where do you think American journalism is right now, and where is it heading?

To be honest, I thought I had already seen everything. But hearing a US president effectively dismiss a murder was shocking. Let’s forget for a moment that this was a journalist. A person walked into their country’s consulate to get documents, and that same country killed them, dismembered them, and disposed of the body. Watching a US president shrug and say, “These things happen,” is deeply revealing. For me, it became a concentrated symbol of where the United States finds itself today. The current president demonstrates not just contempt for the value of human life or for journalism — at times it feels like an active hostility toward facts and toward the people who bring those facts to the public. When a journalist asked him why he invited the Saudi crown prince given his likely involvement in Jamal Khashoggi’s murder, Trump said he “didn’t know” — despite US intelligence findings and a UN report directly pointing to Mohammed bin Salman’s role. So we are living in a very dangerous moment. In the US, facts are increasingly dismissed or distorted, and pressure on the media — especially large newsrooms — is constantly growing. Trump regularly threatens them with massive lawsuits whenever he dislikes coverage. This creates a chain reaction: people feel emboldened to harass journalists online, police or immigration authorities feel freer to detain reporters during protests. The atmosphere has become much more tense and unstable. At the same time, there is very little loud, unequivocal defense of independent journalism. Especially when major broadcasters like ABC or CBS agree to questionable arrangements with Trump in order to avoid lawsuits. You give in once, and it becomes the new normal. Power sees that pressure works. Just last week, Trump called a journalist who asked him an uncomfortable question about his relationship with convicted criminal Jeffrey Epstein a “piglet.” I hope moments like this will harden people’s resolve, because these are precisely the moments when society should say: enough. This is unacceptable, and it requires a response. Independent journalism must be defended openly and loudly. Unfortunately, so far I see less of that defense than I would like.

You travel a lot, speak at many events, and have more opportunities to engage with policymakers. Over the past decade — for us, this began with Russia’s first invasion — almost every conversation about security eventually comes down to fakes, disinformation, and digital technologies. These topics dominate security forums: politicians constantly repeat that media matter and that disinformation is dangerous. Yet at the same time, media budgets — including those of public broadcasters — are being cut. Recently, I was saddened by a decision by one European public broadcaster (I won’t name the country) to shut down a service that produced slower, deeper analytical journalism. Sometimes it feels like everything is moving in the opposite direction: politicians talk more and more about the importance of media precisely because media can be inconvenient for them. But their actual actions are counterproductive. Less support, smaller budgets, problems even for institutions like the BBC. Do you see this contradiction as well? Because to me it looks almost schizophrenic.

It really is a profound cognitive dissonance. Everyone acknowledges that disinformation is one of the key drivers of global instability. But instead of investing more in independent journalism, governments are doing the opposite. In the United States, the work of Voice of America has effectively been dismantled, while Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Radio Free Asia are under pressure. At the same time, NPR and PBS are being weakened. In other words, instead of supporting access to facts, governments are cutting that support, while increasing spending on “hard” security. We see military budgets growing, not investments in the “soft” tools that also directly affect security. But what is even more alarming is something else: it is not only media budgets that are shrinking — there is a growing tendency to portray journalists as a threat. A telling example is how Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth describes the presence of journalists in the Pentagon — as people who supposedly “wander the corridors” and interfere with work. This is how a narrative takes shape that we already see in Israel: the idea that journalism itself poses a security risk. This is an extremely dangerous trend. If journalists are labeled as a threat simply for gathering and verifying facts, it becomes much easier to justify restricting their work. This is no longer just cognitive dissonance. These are active attempts to discredit those who provide society with reliable information precisely when it is needed most.

Journalists are not protected because they are “special” people or because their profession is more important than others. They are protected because a journalist is a mediator between events and society. When a journalist is attacked, it is not just one person who is silenced — an entire community is. What disappears is not a reporter’s voice, but the public’s ability to know what is happening. Protecting journalists has never been about privileges; it has been about function and about the public’s right to know. That is why the word PRESS once meant: “Don’t shoot — I’m not here for myself.” The fact that journalists today hide the word PRESS is not a “new reality,” but a sign of the degradation of rules. But I would like to ask you to formulate the argument: why must journalists be protected?

We need journalists because they are the ones who find and document facts that others try to hide. Mariupol is a telling example: when Russia lied about the bombing of the maternity hospital, it was the presence of journalists that made it possible to document the truth and debunk claims about “actors.” The same applies in peacetime. Investigative journalism has exposed medical scandals like the thalidomide case, water contamination, corruption, and illegal actions by police and courts. This information does not appear on its own. Without it, society becomes more vulnerable. That is why when local journalism disappears, oversight of power weakens in direct proportion, trust within communities erodes, and even taxes tend to rise. This has a direct impact on people’s lives. But we often lose sight of this connection, treating media as something distant and abstract. When a crisis hits, this understanding returns quickly. During the war in Ukraine, or during wildfires in California, radio audiences surged. When the internet went down, radio still worked, and people turned on their radios to understand what was happening. Journalism is not about abstract media institutions. It is about facts, without which we cannot live freely and safely.

Do you track targeted attacks against women journalists? This phenomenon is becoming global. In Ukraine, the organization Women in Media recently conducted a study showing that 80% of women journalists had experienced online violence in one form or another, and 60% admitted that at first they did not even recognize it as violence, perceiving online harassment as mere hate or unwanted attention. Do you see a systemic trend of sexism and misogyny against women in journalism?

We do not conduct surveys of this exact kind, but nearly all research points to the same conclusion: online harassment is primarily directed at women and people from vulnerable groups. If we speak not in numbers but from what we see in practice, the situation is only getting worse, despite years of public discussion of this problem. Part of this is because platforms have loosened rules and accountability for hate speech. Another part is the atmosphere of permissiveness, when political leaders allow themselves public sexist insults. When a president calls a woman journalist a “piglet,” or when, as in the cases of Duterte or Bolsonaro, women journalists are publicly humiliated, it legitimizes misogyny. The internet amplifies it, and punishment becomes increasingly rare. That is why this must be spoken about constantly and why support mechanisms for journalists are essential. We cannot return to the logic of “endure it because that’s how it is.” That is unacceptable.

How do you work with platforms? For journalists from smaller countries, just like for small newsrooms or even governments, it is almost impossible to get through to big tech companies: there is a lack of resources and influence, and it often feels like platforms simply don’t care. CPJ is a US-based organization with high visibility, and most major platforms are headquartered in the US. How do you build relationships with global digital platforms, what do you see as the main challenges, and what priorities do you set for yourselves?

We continue to respond to the most dangerous cases, where journalists face real, immediate threats. But overall engagement from platforms has noticeably declined; interest in systemic solutions is waning. You see this too. Part of this is political — a very deliberate political shift in the United States. At the same time, more and more people are looking for alternatives: moving to other platforms, seeking forms of communication with greater control over content and rules of interaction. In this context, the experience of Maria Ressa and Rappler is particularly telling. For years, they have been working on models of social media built around communities and user participation. This may become one of the few viable paths forward. Major platforms are increasingly unwilling to take responsibility, while state regulation is often too blunt and risks restricting freedom of speech. Alternative platforms may therefore become an important space for protecting journalists, women, and everyone targeted for truth-telling and non-mainstream views.

You have spoken about a new form of pressure on journalists — through the law itself. This is no longer limited to classic defamation lawsuits, but involves the use of other legal provisions: tax law, financial regulations, “technical” violations that allow pressure not only on newsrooms but on individuals. How systemic is this trend today, and what can be done about it?

Abuse of the law is one of the central problems today. Governments have become more sophisticated: accusing journalists of undermining the rule of law sounds persuasive. Acting formally “within the law” is much harder to challenge. That is why in recent years we have increasingly seen authorities persecute journalists not for the content of their reporting, but under other pretexts: taxes, money laundering, national security — ostensibly unrelated to journalism. This produces two effects. The first is a smokescreen: attention shifts from the journalist’s work to suspicions about the individual, creating the impression that we are dealing with a criminal rather than a reporter. The second is long, expensive legal proceedings that exhaust journalists and newsrooms and deter others from pursuing sensitive topics. This “legal warfare” — the use of law as a weapon — is cheaper and less scandalous than physical attacks because it masquerades as legitimacy. That is why it is so difficult to fight. CPJ now involves not only media lawyers but also experts in tax law, international trade, and related fields to defend journalists under these new conditions.

I was deeply struck by Gustavo Gorriti, the Peruvian journalist. He found a non-obvious way to use defamation law: his legal team preemptively warns that any claims labeling their investigations as “fake news” will be treated as defamation. This is an example of how the law can be used not only as a tool of pressure, but also of protection. If a politician says Gorriti’s investigation is fake, they will have to prove it in court. Cases like this give me optimism. Hope also comes from local journalism and the strength of communities. In Ukraine, there are thousands of hyperlocal newsrooms based in villages or frontline areas; they work in extremely difficult conditions and cannot simply be shut down. So my optimism lies in people, communities, and new approaches to journalism. What gives you hope, especially now, when the number of journalists killed is at a record high and the capacity of organizations like yours is limited? Where do you find reasons to believe that things can change not only for the worse?

I remain optimistic because I am convinced that most people in the world value facts. In every country, there are journalists — local, regional, national, international — who, despite threats, are committed to informing the public honestly. I am inspired by their courage. They continue to work even in the most tragic conditions. Every day I see people who knowingly take risks to accurately document what is happening. The least I can do is support them, help them endure, and keep going. That is what gives me strength.

I want to encourage people and remind them: when people distrust someone, it often means they care — trust matters to them. So all the threats posed by disinformation and technology only confirm that our profession is more necessary today than ever.

Yes. Journalists would not be persecuted, imprisoned, or killed at record rates if our work did not matter. No one harms those who are irrelevant. Attacks happen when people are doing something truly meaningful and influential.

I know we will endure and continue to work. Thank you for this conversation and for your honesty. I really want this to be heard not only by journalists, but by a broader audience trying to understand where we are in the world today. And I also want there to be more solidarity with Ukrainians, who are in an extremely difficult situation. I often say that in some countries the profession is being killed, while in ours journalists are being killed. But at least today, journalism in Ukraine remains very strong and resilient.

Ukrainian journalists continue to prove, again and again, how valuable and important this work is. I cannot fully express how deeply I admire what you do and how much respect it inspires in me. You work in conditions that are hard even to imagine, and yet you continue to do your job.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.